I pushed a seed between my teeth and bit down hard, grinding the meat and shell. I looked up, scraping the minced fragments from my tongue, embarrassed that I had neither their skill nor speed. I brought another to my lips, this time dropping the shell before I could close my teeth around it. I watched it tumble to the ground and land amidst a cluster of empty husks sprinkled over the red Turkish earth like stars over the night sky.

‘Nasil?’ I asked desperately. How?

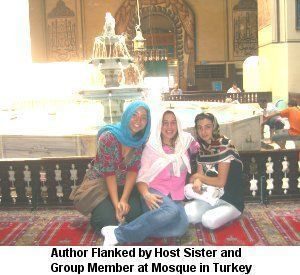

A burst of laughter rose from the veiled women sitting cross legged around me. Cupping a handful of seeds, my host sister Asli came to my rescue.

‘Gezlemek,’ she said. Watch.

Skillfully, she pushed one through the front of her teeth. As she bit down the length of the seed, her teeth pierced the shell repeatedly like the needle of a sewing machine down the seam of a dress.

‘Shimdi sen,’ she said, Now you.

‘Hadi hadi,’ the women urged. After several failed attempts, I finally succeeded.

‘Cok guzel‘ they said proudly, very beautiful. A feeling of warmth washed over me. I did not feel like an American outsider anymore; I had found my place in the village.

I remember arriving in Hoca Key, one of fourteen American teenagers. I watched the bus drive off the dirt path, a cloud of dust swirling in its wake. I sat down at the men’s cafe, terrified, waiting, like a puppy in a cardboard box. At any moment, a family of strangers would take me home. I gazed out into the sea of people, wondering which faces were theirs. Frantically, I recalled every Turkish word I could think of. ‘Imdat,’ I thought. Help me.

I nearly tripped over my bags when I heard my name. It was my host father Muharrem, a tall slender man with rough hands and warm, dark eyes; he had come with my brother Yusuf. I followed them up the winding dirt path towards the house, pausing to let a woman herding a flock of sheep pass by. Groups of women squatted in front of their houses, gossiping and eating sunflower seeds. I felt like I was on another planet. I wondered how I would survive in a rural community when I had never lived outside a major city.

As I watched my father struggle under my bags, I recalled all the useless things I had brought with me–chief among them, an electric straightening iron. I felt ridiculous and out of place. In Hoca Key running water was an uncertain luxury and there were no toilets or showers, just holes in the ground and buckets. Everything from the way we ate on the floor, to the way we entered the house, without shoes, was new to me. I could not go outside unescorted or bare my legs and shoulders. I wondered how my family would react if they saw me wearing my usual shorts and a tank top; all that exposed skin would probably make them faint.It was not until the night when I learned how to eat sunflower seeds that I began to appreciate the village’s strong sense of community and family. As commonplace as it may seem, breaking open that first seed was a momentous occasion for me. After that, everything else seemed easy.

I spent almost every night the same way, eating sunflower seeds and telling stories. If we did not understand each other after exhausting the dictionary and resorting to charades, we just laughed and moved on.

‘Bosvar,’ we said. Nevermind. What surprised me most about my experience was not that I overcame such drastic cultural differences, but how much I enjoyed living there, and how close I became to my family.

The things that I had found so intimidating at first are now the ones I miss the most. I daydream about enjoying sunflower seeds with Turkish neighbors and eating meals on the floor. Sometimes I talk to myself in Turkish so that I will not forget what I learned; I will need those skills when I go back.

Just as clearly as I remember coming, I remember leaving. The entire village was there to see us off. I lagged behind the others, not wanting to leave my family or the place I called home behind, tears streaming down my face.

‘Uc kardes var,’ said my father. You are my daughter.

I looked back at my village as the bus drove away, a wave of dust behind me. I thought about the future. I knew that I could go anywhere and do anything, no matter how far outside my comfort zone. I wonder where I will go next.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.