Rhyolite, Nevada sits in the Bullfrog Hills about 120 miles northwest of Las Vegas, near the eastern boundary of Death Valley National Park.

This ghost town sprang to life in early 1905 after prospectors discovered gold in the surrounding hills, and within just a few years it became one of Nevada’s most promising mining communities.

Today, travelers from around the world venture to this remote desert location to witness the haunting remains of buildings and structures that tell the story of boom and bust in the American West.

The combination of crumbling architecture, desert landscape, and fascinating history creates an unforgettable experience that captures the imagination of photographers, history enthusiasts, and adventure seekers alike.

The Remarkable Rise of a Desert Boomtown

Gold fever transformed an empty stretch of Nevada desert into a thriving metropolis almost overnight.

When prospectors Frank “Shorty” Harris and Eddie Cross discovered rich gold ore in the Bullfrog Mining District in 1904, word spread like wildfire across the West.

Within months, thousands of fortune seekers descended upon the area, setting up tents and shacks that would soon give way to substantial buildings.

By 1907, Rhyolite boasted a population estimated between 3,500 and 5,000 residents, complete with electric lights, water mains, telephones, newspapers, a stock exchange, and an opera house.

The town featured more than 50 saloons, multiple hotels, stores, and even an ice cream parlor.

Three railroad lines connected Rhyolite to the outside world, bringing supplies and carrying away ore from the productive mines.

The Montgomery Shoshone Mine alone produced millions of dollars worth of gold during the boom years.

Walking through the ruins today, visitors can barely imagine the bustling streets filled with miners, merchants, and families who believed they were building a permanent city.

The rapid growth seemed unstoppable, and investors poured money into infrastructure and businesses.

Yet beneath the optimism, the seeds of decline were already present.

The ore deposits, while initially rich, proved less extensive than hoped.

Financial panics back East would soon dry up investment capital.

The story of Rhyolite’s explosive growth represents the classic Western tale of ambition, hope, and the relentless pursuit of wealth that defined the mining frontier era.

Architectural Ghosts Standing Against Time

Few sights capture the essence of abandonment quite like the skeletal remains of once-grand buildings standing alone in the desert.

The most photographed structure in Rhyolite is undoubtedly the ruins of the Cook Bank Building, a three-story concrete structure that once represented financial stability and prosperity.

Its empty window frames now frame nothing but sky and distant mountains, creating a haunting portrait of lost dreams.

The walls, though deteriorating, still stand remarkably intact thanks to the dry desert climate.

Nearby, the old jail building constructed from concrete blocks remains surprisingly well-preserved, its small cells still visible to curious visitors.

The railroad depot, built by the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad, sits quietly with its distinctive architecture slowly succumbing to the elements.

Perhaps most unusual is the Bottle House, constructed entirely from thousands of glass bottles held together with adobe mortar.

Tom Kelly built this quirky structure in 1906 using beer and liquor bottles, creating insulated walls in a place where lumber was scarce and expensive.

The structure was restored in the 1920s and again more recently, making it one of the most complete buildings visitors can explore.

Each structure tells its own story through weathered surfaces and crumbling corners.

Photography enthusiasts spend hours capturing the interplay of light and shadow across these ruins.

The stark contrast between the solid construction and current decay creates powerful visual metaphors about impermanence and the passage of time in the unforgiving desert environment.

The Swift Collapse of a Mining Dream

Nothing lasts forever, especially towns built on the uncertain promise of mineral wealth.

Rhyolite’s decline came almost as quickly as its rise, proving that boom can turn to bust in the blink of an eye.

The financial panic of 1907 dealt the first serious blow to the town’s economy, making it difficult for mining operations to secure the capital needed for continued operations.

When ore production began declining and proved less profitable than initially projected, investors pulled their money out and moved on to the next promising strike.

By 1910, the population had dropped dramatically, with families packing up and leaving for opportunities elsewhere.

The mines closed one by one, taking jobs and hope with them.

By 1916, the power was turned off, and Rhyolite was effectively dead.

Only a handful of residents remained, caretakers of a ghost town in the making.

The speed of the collapse shocked those who had believed in the town’s permanence.

Buildings that had cost thousands to construct were simply abandoned, their contents left behind as families fled.

The railroads pulled up their tracks, and the telephone lines went silent.

Nature began reclaiming the land almost immediately, with desert winds and occasional rains starting the slow process of erosion.

Today, this rapid rise and fall serves as a cautionary tale about the volatility of resource-dependent communities and the unpredictable nature of mining ventures in the American West.

Desert Landscape and Seasonal Beauty

The Bullfrog Hills provide a dramatic backdrop to the ruins, creating a landscape that changes character with the seasons and time of day.

Spring brings surprising bursts of color when desert wildflowers bloom after winter rains, carpeting the ground around crumbling foundations with yellows, purples, and reds.

These brief displays transform the ghost town from a study in browns and grays into a celebration of life persisting in harsh conditions.

Summer temperatures soar above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, creating shimmering heat waves that distort distant views and test the endurance of visitors.

Early morning and late afternoon offer the best visiting conditions, when golden light bathes the ruins in warm tones and long shadows add drama to every photograph.

Fall brings cooler temperatures and crystal-clear air, with visibility extending for dozens of miles across the basin and range topography.

Winter occasionally dusts the hills with snow, creating surreal contrasts between white peaks and desert valleys.

The proximity to Death Valley National Park means the landscape shares that region’s stark beauty and extreme conditions.

Joshua trees dot the surrounding hills, their twisted forms adding to the otherworldly atmosphere.

Creosote bushes and desert scrub provide subtle greens and grays across the terrain.

At night, the absence of light pollution reveals spectacular star displays, with the Milky Way stretching across the sky above silent ruins.

The landscape itself becomes part of the ghost town’s story, an indifferent witness to human ambition and failure.

The Goldwell Open Air Museum Experience

Art and abandonment intersect in unexpected ways just outside Rhyolite’s main ruins.

The Goldwell Open Air Museum features large-scale outdoor sculptures that create thought-provoking conversations with the ghost town setting.

Belgian artist Albert Szukalski created the most famous installation, “The Last Supper,” featuring ghostly white figures draped in plaster-soaked fabric standing in the desert.

These spectral forms echo the theme of abandonment while adding contemporary artistic commentary to the historical site.

The contrast between modern art and century-old ruins creates a unique viewing experience found nowhere else.

Other sculptures include a ghost miner by Hugo Heyrman and various pieces that interact with the landscape in surprising ways.

The museum operates as a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving these outdoor artworks despite the challenging desert environment.

Visitors can walk among the sculptures freely, experiencing how art transforms our perception of place and history.

The installations weather and change over time, much like the ghost town buildings themselves, creating an ongoing dialogue about permanence and decay.

Photography opportunities abound, with sculptures providing foreground interest against backgrounds of ruins and mountains.

The museum hosts occasional events and artist residencies, bringing creative energy to this remote location.

For many travelers, the combination of historical ruins and contemporary art installations makes Rhyolite more than just another ghost town, elevating it to a destination that engages both mind and imagination in unexpected ways.

Photography Paradise for Visual Storytellers

Camera shutters click constantly at Rhyolite as photographers discover endless compositions among the ruins.

The combination of architectural elements, desert landscape, and dramatic lighting creates ideal conditions for visual storytelling.

Sunrise and sunset offer the most spectacular opportunities, when low-angle light rakes across textured walls and creates long shadows that emphasize form and depth.

The golden hour transforms ordinary ruins into glowing monuments bathed in warm tones.

Midday harsh light presents different challenges but can produce striking high-contrast images that emphasize the stark reality of abandonment.

Empty window frames function as natural frames within frames, allowing photographers to compose shots that direct the viewer’s eye toward distant mountains or sky.

Texture enthusiasts find endless subjects in weathered wood, crumbling concrete, rusted metal, and peeling paint.

The Bottle House provides unique opportunities with light filtering through colored glass.

Night photography reveals star trails arcing over silent buildings, while moonlight creates mysterious moods perfect for long exposures.

Many photographers return multiple times, finding new angles and perspectives with each visit.

The remote location means fewer crowds interfering with shots, though weekends and holidays bring more visitors.

Instagram and photography websites feature thousands of Rhyolite images, yet each photographer manages to find their own unique vision of the place.

The site’s photogenic qualities have made it a favorite location for photography workshops and tours focused on landscape and architectural photography techniques.

Practical Visitor Information and Access

Getting to Rhyolite requires some planning, as this remote location sits miles from major services and amenities.

The ghost town is located along Highway 374, approximately four miles west of Beatty, Nevada, the nearest town with services.

Beatty offers gas stations, restaurants, and lodging options for visitors planning to explore the area.

The drive from Las Vegas takes about two hours heading northwest, making Rhyolite a feasible day trip for those based in the city.

Visitors approaching from Death Valley National Park will find Rhyolite just outside the park’s eastern boundary, accessible via a short detour.

The site is open year-round with no admission fees, making it accessible to all travelers regardless of budget.

Parking areas near the main ruins accommodate multiple vehicles, though facilities are minimal.

No restrooms, water, or shade structures exist at the site itself, so visitors must come prepared.

Bringing plenty of water is essential, especially during summer months when temperatures become dangerous.

Sturdy shoes are recommended, as exploring ruins involves walking on uneven ground with potential hazards like broken glass and unstable structures.

Cell phone service is unreliable or nonexistent, so travelers should not depend on mobile devices for navigation or emergencies.

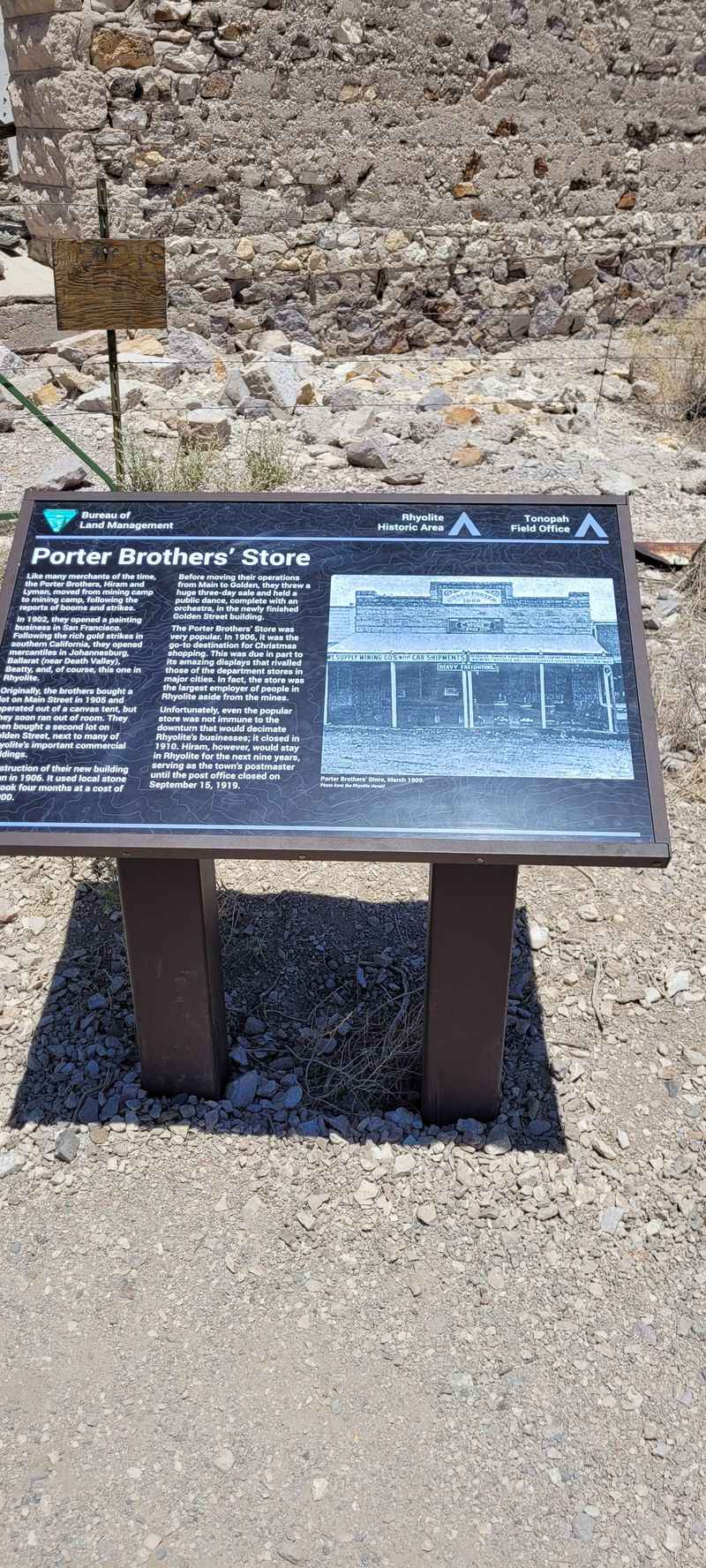

The Bureau of Land Management oversees the site, and visitors are expected to respect the ruins by not climbing on fragile walls or removing artifacts.

Taking only photographs and leaving only footprints ensures these historic structures remain for future generations to appreciate and study.

Historical Preservation and Educational Value

Preserving ghost towns presents unique challenges that balance public access with protecting fragile historic resources.

Rhyolite benefits from its designation as a historic site managed by the Bureau of Land Management, which provides some protection against vandalism and unauthorized alterations.

Interpretive signs throughout the site offer historical context, helping visitors understand what they’re seeing and why these ruins matter.

The town serves as an outdoor classroom where history comes alive through tangible remains rather than just textbook descriptions.

Students and researchers study Rhyolite to understand mining history, Western expansion, architectural techniques, and the social dynamics of frontier communities.

The rapid boom and bust cycle provides lessons about economic sustainability and the risks of single-industry dependence.

Local history enthusiasts and organizations work to document the site through photographs, oral histories, and archaeological surveys.

These efforts create archives that capture the current state of ruins before further deterioration occurs.

Some stabilization work has been done on the most significant structures, particularly the Bottle House, which has undergone multiple restoration efforts.

However, most buildings are left to decay naturally, accepting that time and weather will eventually claim them.

This approach reflects philosophical debates about preservation: should we stabilize and maintain ruins indefinitely, or allow natural processes to run their course?

For now, Rhyolite exists in a middle ground, protected enough to remain accessible but authentic enough to convey the genuine experience of abandonment and the passage of time.

The Enduring Appeal of Ghost Town Tourism

Something about abandoned places captures human imagination in ways that pristine historical sites sometimes cannot.

Ghost towns like Rhyolite offer visceral connections to the past, where visitors walk the same streets and touch the same walls as people who lived over a century ago.

The absence of crowds and commercial development allows for contemplative experiences rarely possible at more popular tourist destinations.

Standing alone among ruins, travelers can let their imaginations reconstruct the bustling town that once existed, hearing phantom sounds of commerce and conversation.

This type of imaginative engagement creates memorable experiences that resonate long after the visit ends.

Ghost towns also satisfy curiosity about how our civilization might look after we’re gone, offering glimpses into processes of decay and nature’s reclamation.

For adventure seekers, the remote location and minimal infrastructure add elements of exploration and discovery.

History buffs appreciate the authentic artifacts and structures that haven’t been sanitized or reconstructed.

Photographers find inspiration in the visual drama of abandonment.

Artists and writers draw creative energy from the melancholy beauty and stories embedded in every wall.

Families use visits as educational opportunities, teaching children about history, geology, and the importance of preserving cultural heritage.

Rhyolite’s accessibility, photogenic qualities, and well-preserved ruins make it one of the West’s premier ghost town destinations, attracting thousands of visitors annually who seek authentic encounters with the past in Nevada’s unforgiving but beautiful desert landscape.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.