California wears its history on its sleeve, and some of its most fascinating places are the ones with a few scuffs and stories.

You can feel the shift from fame to fade as you step into towns, bases, and shorelines that once commanded headlines.

These landmarks invite you to slow down, look closer, and read the layers in wood grain, concrete cracks, and desert dust.

If you are curious about where glory went and what remains, this list will be your map.

By the end, you will have a plan to see and photograph a California that is honest, beautiful, and very much alive.

1. Bodie State Historic Park

Step into the extraordinary time capsule that is Bodie State Historic Park, a legendary Gold Rush ghost town suspended in time on a remote high desert plateau over 8,300 feet in the Eastern Sierra.

The town rose incredibly fast, exploding into a notorious boomtown after a rich gold strike was made around 1876, drawing a wild mix of miners, merchants, and outlaws who epitomized the raw, frenetic energy of the Gold Rush era.

At its peak around 1879, the population swelled into the thousands, and the air was filled with the deafening roar of stamp mills processing millions in gold and silver ore.

Life here was cheap, with sixty-five saloons open for business, and local newspapers often chronicled the gunfights, major fires, and instant fortunes that defined the town’s rough-and-tumble, lawless vigor.

However, the fever broke when the richest gold veins thinned and the cost of deeper mining mounted; the thousands who had rushed in soon drifted away, leaving behind the sobering reality of a spectacular bust, which was finally cemented by a catastrophic fire in 1932.

Fortunately for us adventurers, California made the brilliant choice to protect what remained in a special condition called “arrested decay,” which means park staff brace roofs and stabilize foundations without ever polishing away the age or restoring the buildings to new.

That unique decision froze an exact moment in time, creating an unbelievably authentic experience where plates still sit on tables, and ledgers rest on counters in the post office as if someone might return after lunch, offering a view that is not reimagined for nostalgia.

As you walk along the dusty streets today, you can explore the roughly 110 remaining buildings, which lean with a quiet grace against the thin mountain air, standing as a faithful record of a massive boom turned quiet.

Peering into the windows of the general stores, you see bottles and tools in faded light, and in the old schoolhouse, the desks maintain their stern order beneath chalk dust.

Your footsteps crunch softly in the profound silence, and each doorway frames a beautiful, haunting scene that feels completely paused but still breathing.

Photographers are drawn to the pale sagebrush, the deep, long shadows cast by the sun on the weathered pine, and the dramatic backdrop of storms rolling over the brown hills, which provide ready-made, atmospheric compositions.

The rusty hinges, the diagonals of siding, and the antique glass reflecting the clouds all add to the visual drama, creating an unforgettable, cinematic landscape.

While summer and fall are easier to visit, you must check conditions, as winter can close the access road entirely or require long detours and snow-capable vehicles, but that very difficulty ensures that the rare clear, snow-covered day is experienced as a profound, personal victory over the elements.

2. Salton Sea North Shore Beach and Yacht Club

The Salton Sea filled the Imperial Valley basin in 1905 when a canal breach sent the Colorado River surging into low desert flats, inadvertently creating California’s largest lake.

By the 1950s, this accidental body of water had become the glamorous “Salton Riviera,” attracting boat races, celebrity weekends, and a bustling calendar of sunny spectacles.

The height of this mid-century ambition arrived with the 1962 opening of the North Shore Beach and Yacht Club at 99155 Sea View Dr, Mecca, CA 92254, a pristine vision of crisp, modernist geometry designed by the renowned architect Albert Frey.

However, environmental stress rapidly unraveled the dream, as continuous evaporation caused the salinity to rise above that of the Pacific Ocean, and agricultural runoff fed destructive algal blooms.

These ecological pressures led to massive fish die-offs, creating a smell that drove visitors away permanently, while once-busy marinas silted in and docks were stranded high and dry on crusty salt flats.

The Yacht Club eventually closed its doors, and travel brochures faded to memory as vandalism spread and the vast shoreline began its decades-long recession, leaving behind brittle salt and bone.

Fortunately, hope returned in 2010 when Riverside County undertook the commendable effort to fully restore the Yacht Club building, reopening it as a much-needed community center and visitor hub complete with interpretive exhibits.

The lines remain unmistakably Frey, still projecting a sense of calm and buoyancy against the desert heat shimmer, with the beautiful interior now hosting local meetings and essential community programs.

Yet, much of the surrounding shoreline still shows cracked foundations and abandoned concrete pads from the former resort towns, and that immediate contrast tells the region’s longer, complex story at a glance.

The images captured here often lean toward the surreal, dominated by the bleached fragments of fish skeletons crunching underfoot and old telephone poles marching across the barren playa toward a shrinking horizon.

Conversely, the bright white planes of the meticulously restored clubhouse deliver a hopeful counterpoint, glowing serenely in the soft desert evening light.

You can effortlessly frame a powerful scene where the optimism of the mid-century dream and the profound reality of environmental loss sit side-by-side, creating a composition that stays with you long after you drive north toward other California deserts.

Access to the Yacht Club is straightforward via paved roads, though visitors must prepare for the often-intense summer heat and the wind that can unexpectedly lift gritty dust that stings the skin and eyes.

Visiting during the morning offers gentler light and clearer, more serene views across the water toward the distant Santa Rosa Mountains, providing the best photographic conditions.

Finally, plan extra time to explore the unique outdoor art installations and study the interpretive signs that are vital for mapping the sea’s constantly changing edges, enriching your understanding of this compelling, tragic, and historically significant landscape.

3. Calico Ghost Town

Calico boomed in the 1880s on a ridge above the Mojave as silver strikes drew miners and merchants in waves, quickly becoming one of the largest and most famous mining towns in California.

Its rapid rise to prominence was fueled by a massive silver discovery in 1881, leading to a population peak estimated at around 3,500 people, all drawn by the promise of riches in the remote desert.

The town rivaled Bodie in production and noise, with stamp mills pounding ore day and night and stagecoaches rattling in regularly with freight and passengers across the harsh terrain.

Can you imagine the constant thunder from the twenty-three working mines and the bustle of the more than fifty saloons that lined its historic streets during its peak silver production years?

When silver prices crashed dramatically with the passage of the Sherman Silver Purchase Repeal Act in 1893, the work dried up almost overnight, and the settlement slowly emptied, becoming just another victim of the boom-and-bust cycle, left to the sun and wind.

In the 1950s, Walter Knott, the famed founder of Knott’s Berry Farm, purchased the historical site and embarked on an ambitious project to rebuild much of the streetscape using period photographs as a faithful guide.

His vision was to create an accessible frontier experience that expertly balanced genuine historical elements with the family-friendly charm and clear wayfinding necessary for a modern tourist attraction.

Knott’s crews meticulously restored or rebuilt five of the original buildings while constructing the remainder using era-appropriate architecture, ensuring a neat and engaging window into the late 19th century.

San Bernardino County later took over the management, maintaining the park as a clean, curated window onto a lively and ultimately invented version of the Old West that is still immensely popular today.

Today, you step right into a neat, easily navigable main street featuring attractions like a narrow-gauge train ride, tours through original mine tunnels with hard hats, and plenty of quaint shops selling jewelry, rocks, and souvenirs.

While you explore, interpretive signs throughout the park clearly explain the details of the silver mining methods and the town’s history, while performers offer occasional skits that lean playful and theatrical rather than historically gritty.

The main paths are wide and well-graded, allowing you to easily navigate with strollers and wheelchairs, providing a much lower-stress experience than visiting rugged, undeveloped ruins like Bodie.

Photographs here pop with bright, fresh paint, tidy boardwalks, and a cloudless desert blue that beautifully flatters every reconstructed façade, making it a perfect spot for vivid, sunny snapshots.

This picturesque scene contrasts sharply with the subdued browns and genuine disrepair of more authentic ghost towns, inviting easy, well-lit portraits and celebratory group shots for families and tourists.

Whether you need a quick shot of a classic saloon or a staged photo with wagon wheels and false fronts, Western-themed images find simple, highly photogenic backdrops in every corner and staged alley.

Calico sits conveniently near Interstate 15, meaning travel planning stays wonderfully simple for road trippers crossing California, heading to Las Vegas, or exploring the vast Mojave Desert.

Be aware that the park hosts seasonal events and festivals, which bring seasonal crowds, so arriving early in the morning rewards you with better light, cooler temperatures, and more space for quiet exploration.

If you want a lightweight, engaging taste of California mining lore without the challenge of remote, rough dirt roads and unpaved access, this beautifully maintained historic site is the friendliest, most accessible on-ramp available.

4. Fort Ord National Monument and CSU Monterey Bay

Fort Ord trained soldiers from 1917 to 1994 on a magnificent coastal terrace that ultimately shaped the lives of more than 1.5 million service members during its tenure.

As one of the largest and most important U.S. Army posts, the base anchored the entire Central Coast economy with sprawling rifle ranges, simple barracks, and vast parade grounds spread across rolling sand dunes and sun-drenched, oak-dotted hills.

Cultural history threads deeply through the site with famous alumni like the actor and director Clint Eastwood, alongside a brief, pre-fame stint by the legendary musician Jimi Hendrix, who served here as a paratrooper in the early 1960s, often cited in local lore.

The base’s official closure in 1994 ended a nearly century-long military era and launched a complex, years-long transition as various government agencies began the massive task of dividing the land for education, conservation, and new civil redevelopment.

Rising from former base parcels, California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB) was established in 1994, repurposing existing buildings and constructing new, modern classrooms, dorms, and research facilities on the former military grounds.

Crucially, vast acreage was designated as the Fort Ord National Monument in 2012, permanently preserving rare patches of coastal maritime chaparral and opening up a wide web of former military roads now enjoyed as public trails.

Today, visitors find themselves exploring miles of scenic singletrack and wide fire roads that curve gently over sandy rises and drop into shaded oak canyons, offering adventures for hikers, cyclists, and equestrians alike.

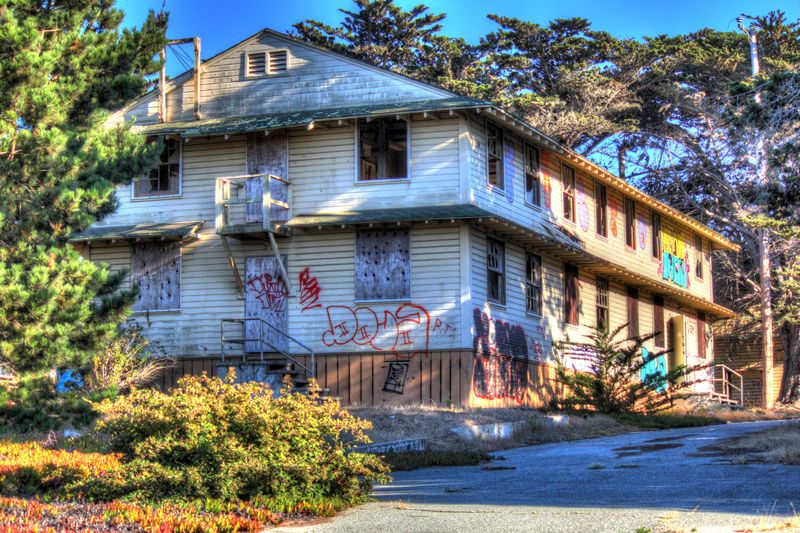

Cyclists often spin past crumbling concrete pads and the graffiti-tagged, windowless shells of abandoned military buildings that currently await environmental remediation or removal, all while hawks and kestrels hover lazily above.

The juxtaposition of the sweet, wild thyme scents rising from the trails with the cracked, buckled asphalt of abandoned streets tells a compelling story of nature stubbornly and gracefully folding human history into the present landscape.

Images here often crackle with an intense contrast as the glassy, modern architecture of the new university halls meets the derelict, repetitive rows of boarded-up barracks holding sunlit rectangles where windows once were.

Photographers frequently frame subjects through broken chain-link fences, using stray shadows and the silhouettes of old radio towers set against the dramatic fog banks that regularly roll in from Monterey Bay.

The monument’s high ridges open broad, panoramic views toward the distant water, vistas that glow warmly at golden hour and strongly reward patient, quiet pacing away from the busier campus areas.

Trailheads sit conveniently near the university campus and along major access points, featuring clearly marked parking lots and kiosks that mark loops of varying length and grade, suitable for all skill levels.

Spring wildflowers splash brilliant, unexpected color across the sandy soils, while the clarity of the fall brings cool air, perfect conditions for a brisk hike, and spectacular cooler-weather rides.

Always respect the posted closures and warnings, as some structures remain unsafe and require environmental remediation, and restoration work continues quietly across various key corridors within the monument.

5. Lincoln Heights Jail

The infamous Lincoln Heights Jail opened its doors in 1931, showcasing a blend of bold Art Deco lines and Spanish Colonial Revival flourishes that were intended to project civic authority and permanence.

This massive structure served the needs of Los Angeles through some of its most turbulent decades, but its history is tragically marked by severe overcrowding and notorious episodes, including the infamous 1951 “Bloody Christmas” police brutality scandal.

During the controversial Zoot Suit Riots era of the 1940s, large numbers of Mexican American youths were detained here, and the detentions left a deep, long shadow that still distinctly colors the building’s dark and complicated reputation today.

The massive jail officially closed its operational doors in 1965, and for decades, the site sat mostly vacant as the city and various agencies endlessly debated reuse plans, and budgets continually shifted with each new, failed redevelopment proposal.

Due to its vast, imposing architecture, filmmakers quickly discovered the labyrinth of empty cell blocks and industrial corridors, and the site soon became a frequent, moody set for music videos and major motion pictures.

Its pop culture visibility was cemented through notable appearances in big-budget films like Iron Man 2 and the iconic Lady Gaga music video Telephone, ensuring its brooding aesthetic is recognized on screens worldwide.

Today, the hulking, beautiful structure is officially protected as a Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument, though its ultimate future and specific reuse remain in ongoing negotiation and public debate.

Security fencing and numerous warnings strictly keep casual explorers and urban adventurers out of the building, while city-led efforts currently aim toward ambitious proposals for affordable housing and community-focused mixed-use developments.

Passionate community groups actively advocate for historical preservation and push for equitable benefits from the site’s redevelopment, aiming to honor the difficult past without repeating any of its inherent social harms.

Photographers absolutely favor the monumental exterior where the strong repetition of identical windows and imposing buttresses creates graphic, rhythmic compositions under the dramatic slanting light of the afternoon sun.

The building’s exposed materials—the deep weather streaks, the heavily chipped paint, and the worn concrete – add compelling texture that reads beautifully and clearly, especially in striking black and white or muted color palettes.

The sheer massing and geometry of the structure turn its corners into cinematic stages, giving the façade a deeply familiar look that viewers recognize instantly from screens, film posters, and album covers.

Access for visitors involves sticking strictly to public sidewalks and safe vantage points near the perimeter, as interior entry is restricted due to both safety concerns and ongoing redevelopment negotiations.

You can perfectly time your visit for the late afternoon when the shadows lengthen and deepen the architectural details across the pilasters and parapets, enhancing the building’s formidable visual weight.

As the various housing and mixed-use projects advance, expect to see necessary visual changes, but the structure’s unique, brooding presence will certainly continue to anchor a very specific, complicated slice of California memory for decades to come.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.