You ever stand on a quiet stretch of road and try to imagine a whole town breathing there? I did that by the Dolores River in western Colorado, and it felt like the canyon walls were keeping a secret.

The place is Uravan, a cliffside company town that vanished because contamination made staying impossible.

If you are up for a road trip through Colorado with a story that sticks, let me walk you through what you will actually see and feel.

A Town Built Into The Canyon

Let me start with the part that grabs you the second you roll in.

The canyon squeezes the road like it is trying to keep you honest.

You have the Dolores River glinting, the cliffs leaning, and a hush that makes old stories louder.

This is the former townsite of Uravan, tucked along CO 141 near mile markers you will notice only after the fact.

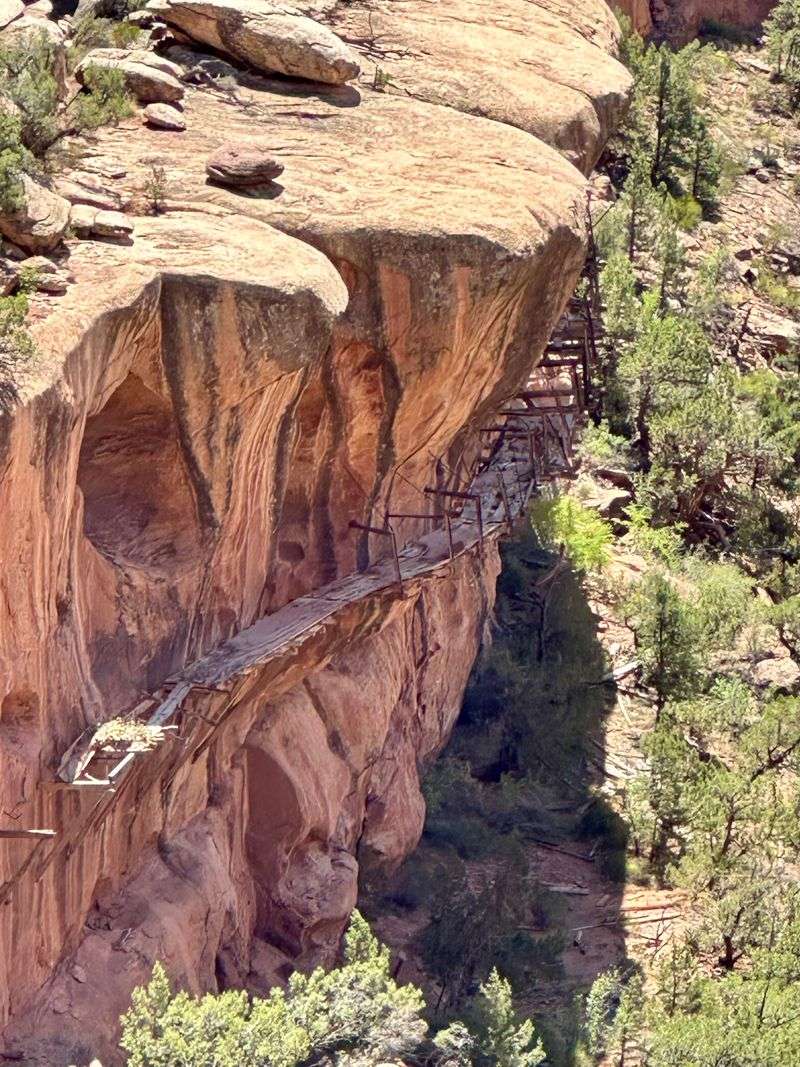

The nearest mapped anchor now is the Hanging Flume Overlook at CO 141, Naturita, which is how I navigate into the corridor.

You pull over, step out, and the wind bounces off the stone like it is returning mail.

The town was set into benches carved from the slope, which you can still read as flat scars and odd berms.

Nothing stands because everything was taken down for safety.

The openness feels huge, but the ghosted grid hints at where porches and sidewalks once lived.

If we park near the Dolores River crossing by CO 141, the view lines up with old photos surprisingly well.

The canyon is the constant, patient and unblinking.

You get that mix of awe and ache that only Colorado’s high desert seems to carry.

I would keep your expectations simple.

You are looking for shapes, not buildings.

The setting does most of the talking.

Why Uranium Drew People Here

You know how places catch a wave and ride it hard?

In this canyon, the wave was uranium and vanadium, minerals tucked in the sandstone and shale like secret pockets.

People came because the work was steady and the purpose felt big.

The processing plant sat near the Dolores River corridor by CO 141, Naturita, with haul roads threading out to the benches.

Ore came down from the mesas and rolled into crushers, then into circuits with chemicals that did their quiet, potent job.

The canyon made a wall that kept everything close.

Colorado’s western slope has a long relationship with hardrock mining, and Uravan slotted right into that story.

The company built housing because distance here is not small.

A short commute can be the difference between seeing your kids before dark or not.

Standing near the road pullouts by the San Miguel and Montrose County line, you can map the old logistics just by line of sight.

River for water intake. Flat yard for stockpiles.

It was a practical place, not a pretty one, and that honesty still hangs in the air.

You do not need signs to feel how purposeful it all was.

The canyon held the work, and the work held the town.

How The Company Town Functioned

Picture a grid tucked against stone, small houses lined up like they were trying to stay out of the wind.

That was the rhythm here.

Work shifts set the clock, and the canyon echoed with pickup doors and gravel under boots.

The school, store, and clinic once clustered around the flatter ground.

Families walked short routes because everything hugged the benches.

You can still see where a sidewalk might have run by the way the ground sits a touch smoother.

Community in a place like this is more than a word.

The canyon makes neighbors because there is not much space to be anything else.

Folks swapped tools, shared rides, and watched the river come up after storms.

When I stand by the roadside turnout near the Dolores River bridge, the whole layout feels very close to the surface.

The terraces are like pages you can still turn with your eyes.

Colorado does that a lot, holding memory in plain sight.

There is no nostalgia machine here, just trace lines and an honest quiet.

You will not find storefronts or porches.

You will find the shape of daily life in the dirt.

Contamination That Could Not Be Contained

This part is heavy, but it is the reason the town is gone.

Processing uranium and vanadium left tailings, residues, and contaminated soil that did not play nice with wind or water.

Once it spread, there was no putting it neatly back in the box.

Standing near CO 141 by the Dolores River crossing you will spot areas that look oddly smooth or capped.

Those surfaces are deliberate, part of cleanup that reshaped the ground to stabilize it.

Signs ask you to keep your curiosity on the safe side of the fence.

Colorado’s dry air looks clean, but particles ride thermals and settle where you wish they would not.

Groundwater does its own slow travel through alluvium and fractured rock.

The canyon’s tight geometry kept operations efficient and made containment harder when things moved.

Most structures were demolished, soils were removed or consolidated, and the shapes you see now come from that work.

It is restoration and scar at the same time.

The quiet is not empty, it is careful.

I treat this stretch like a place that deserves distance and attention.

We can look, learn, and leave no trace.

That is the deal when a landscape carries a past like this.

The Decision To Remove Everyone

Imagine getting a letter that says your town will not be your town much longer.

That is how the end began here.

Safety won out over staying, and the choice stopped being a choice.

When I pull off along CO 141, I try to picture kitchen tables where families read the news.

The canyon probably felt smaller those days.

You can almost hear the long pauses.

The removal plan moved step by step, and daily life unraveled into boxes and goodbyes.

Company towns can fold fast because one decision touches everything.

School, store, neighbors, all packaged into memory.

Colorado has many places where boom rolled into quiet, but this was more final.

Demolition followed relocation.

The ground you see now was scraped and shaped to make the site safer for the long run.

I do not dramatize it when we drive by.

The road keeps rolling, the river keeps talking, and the canyon holds the echo of a town that had to go.

That is the real story.

Families Forced To Leave

There is a bend in the river where the wind feels like it is carrying voices.

I think about living rooms turned into staging zones with labels and tape.

Leaving is work even when you agree it is necessary.

You can line up the ridgelines with old photos and feel how compact everything was.

Neighbors were steps apart, not blocks.

That closeness makes departure feel bigger.

Folks scattered to other Colorado towns, some to other states, chasing jobs and steadiness.

Traditions do not pack neatly, so they ride along in the small things.

You keep a key that no longer opens anything because your hand still knows it.

On the ground now, the flat pads and faint road cuts are like stage directions with no cast.

You read them and build the scene in your head.

The river helps, steady as a heartbeat.

I like to pause at a safe turnout, look both ways, and give the past a minute.

Not to be sad for sport, just to be respectful.

A whole community learned how to say goodbye here.

What Remains At The Site Today

So what do you actually see if we go today?

You see a canyon that feels oversized for what is left on the ground.

You see river, road, benches, and a lot of intentional emptiness.

The easiest landmark for us is the Hanging Flume Overlook at CO 141, because from there the corridor opens in both directions.

Drive slow and use the signed pullouts.

The site itself is a patchwork of reclaimed areas and monitored ground.

No buildings, no fences you walk through, no museum at the center.

Instead, there are occasional markers and the kind of terrain that tells you what not to do.

Stay on the road, keep your eyes sharp, and let the distance do its work.

Colorado’s light is a gift out here, bouncing off varnished rock and making small details pop.

You will notice where crews contoured slopes to manage runoff.

You will notice where native plants are trying another season.

It is not a stop for checking boxes.

It is a pause to read a landscape that changed to protect people. That is enough.

Why Uravan Became A Warning

If there is a lesson tucked into these walls, it is about scale and care.

Work and place have to fit each other, and here they finally did not.

The cost ended up being the town itself.

On CO 141, the drive strings together sites that make the point clearly.

Mines, mills, flumes, and then the quiet where a community used to be.

It reads like a sentence with a hard pause.

Colorado keeps its warnings visible without turning them into spectacles.

Uravan sits in that category, a reminder that cleanup is possible and also complicated.

Safer ground sometimes means no ground for living at all.

I like that the canyon still gets the last word.

The river keeps time.

The road gives us a way to witness without pushing in.

When we plan this trip, we treat it like a respectful visit to a place that did its job and then stepped back.

We carry the story, not souvenirs.

And we leave the landscape exactly as we found it.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.