Think you’ve tasted real cheese? We’re talking about authentic Amish cheese, hand-stirred in copper kettles, aged to perfection, and created without a single modern shortcut.

No machines rushing the process, no additives speeding things up, just pure tradition passed down through generations. Some say it’s the best cheese in the state, maybe even the region.

Others argue you can get the same quality anywhere. So what’s the truth?

Is this slow, painstaking method really worth the hype, or is it just nostalgia dressed up as craftsmanship?

Whether you’re a cheese purist or a curious foodie, this journey into Oklahoma’s Amish cheesemaking tradition will challenge everything you thought you knew about what goes into that block of cheddar in your fridge.

Hand-Stirred Copper Kettles: The Heart of Traditional Cheesemaking

At the center of the cheesemaking process stand massive copper kettles that have been in use for generations. These aren’t decorative antiques or museum pieces, they’re the actual vessels where milk transforms into cheese every single day.

Copper conducts heat evenly, allowing for precise temperature control without the need for electronic thermostats or automated systems.

Watching a cheese maker stir curds by hand is mesmerizing. Using long wooden paddles, they move through the mixture with practiced rhythm, breaking up curds to just the right consistency.

Their movements look effortless, but this is skilled labor that requires years to master. Too much stirring and the curds break down too fine.

Too little and they clump unevenly.

The physical demands of this work are considerable. Stirring hundreds of pounds of curds for extended periods builds forearm strength that would impress any athlete.

Yet the cheese makers maintain their steady pace, checking texture with their hands, adjusting technique based on subtle changes they can feel but might struggle to explain in words.

Modern cheesemakers use mechanical stirrers that can be programmed and left to run. The Amish approach rejects this convenience, believing that human attention throughout the process produces superior results.

After tasting the difference, it’s hard to argue with their philosophy.

Raw Milk: Starting With the Purest Ingredients

Quality cheese begins with quality milk, and the Amish cheese makers in Oklahoma source theirs from local dairy farms that share their commitment to natural methods. These aren’t massive industrial operations with thousands of cows.

Instead, milk comes from smaller herds where animals graze on pasture and receive individual attention.

Raw milk, unpasteurized and full of natural bacteria, forms the foundation of authentic Amish cheese. This might sound alarming to modern consumers accustomed to heavily processed dairy products, but raw milk contains enzymes and beneficial bacteria that contribute to cheese’s complex flavor profile.

When handled properly by experienced cheese makers, raw milk produces cheese with depth and character that pasteurized versions simply cannot achieve.

Each morning, fresh milk arrives at the cheese house still warm from the dairy. The cheese makers inspect it carefully, checking for any off odors or unusual appearance.

Their standards are exacting because they know that everything that follows depends on starting with perfect milk.

Oklahoma’s climate and grasslands produce milk with distinctive characteristics that show up in the finished cheese. The terroir of cheese, if you will, reflects the local environment just as wine does.

Cheese made here tastes unmistakably of this place, carrying flavors that can’t be replicated elsewhere.

Once the milk is in the kettle, the real transformation begins with the addition of starter cultures. These are living bacterial colonies that have been maintained and passed down through generations of cheese makers.

Unlike commercial cultures purchased from supply companies, these traditional starters carry unique characteristics developed over decades or even centuries.

The cheese makers guard their cultures carefully, treating them almost like family heirlooms. Each batch of cheese receives a portion of culture from the previous batch, creating an unbroken chain that connects today’s cheese to wheels made by ancestors long gone.

This continuity gives Amish cheese its distinctive character.

Adding culture is a precise operation despite appearing simple. Temperature must be exact, timing carefully calculated, and the amount measured with practiced accuracy.

Too much culture and the cheese develops off flavors. Too little and it won’t acidify properly.

The cheese makers rely on experience and intuition, making tiny adjustments based on factors like seasonal temperature changes or subtle variations in the milk.

Watching these bacteria work is invisible to the eye, but the cheese makers know what’s happening at a molecular level. They can sense the progress by smell, by the way the milk begins to thicken, by subtle changes in appearance that would escape an untrained observer’s notice.

Rennet and Coagulation: Turning Liquid Into Solid

After the cultures have had time to work, rennet enters the picture. This enzyme, traditionally derived from the stomach lining of young calves, causes milk proteins to coagulate and form curds.

It’s a transformation that seems almost magical, as liquid milk suddenly becomes a solid mass with a consistency somewhere between custard and tofu.

The Amish cheese makers use animal rennet rather than vegetarian alternatives or microbial substitutes. Purists insist that traditional rennet produces superior texture and flavor, and after tasting the results, many converts agree.

The rennet is added in carefully measured amounts, then the kettle is left undisturbed while coagulation occurs.

Patience defines this stage. Nothing visible happens for a while, then suddenly the milk begins to set.

The cheese makers check readiness by cutting a small test portion and observing how it breaks. When the timing is perfect, they cut the entire mass into uniform cubes using long-bladed knives, creating the individual curds that will eventually become cheese.

Cutting curds is an art form. The size of the cut affects moisture content in the finished cheese.

Larger curds retain more moisture, producing softer cheese. Smaller curds release more whey, resulting in harder, drier varieties.

The cheese makers adjust their cutting technique based on what type of cheese they’re making that day.

After cutting, the curds must be stirred continuously while being gently heated. This is where the truly labor-intensive nature of traditional cheesemaking becomes apparent.

For hours, the cheese makers stand at their kettles, stirring with wooden paddles in smooth, consistent motions that keep the curds moving without breaking them apart.

Temperature rises gradually, just a few degrees every fifteen minutes or so. Rush this process and the curds develop a rubbery texture.

Heat too slowly and they don’t release enough moisture. The cheese makers monitor progress constantly, adjusting heat and stirring speed based on how the curds look and feel.

Your arms would give out after fifteen minutes of this work. The cheese makers keep going for several hours, maintaining their steady rhythm through sheer stamina and determination.

They chat while they work, sharing news and stories, but their hands never stop moving. The physical endurance required is remarkable.

As the curds cook, they shrink and firm up, releasing whey that pools in the kettle. The cheese makers test texture by squeezing handfuls of curds, checking for just the right amount of spring and resistance.

When the curds reach the perfect consistency, they drain off the whey and move to the next stage.

Pressing and Forming: Shaping the Final Product

Once the curds reach the proper texture, they’re transferred into molds where pressure will compact them into solid wheels or blocks. The molds are simple affairs, usually wooden frames or metal hoops lined with cheesecloth.

Nothing fancy, nothing automated, just functional tools that have worked for generations.

The curds go into the molds while still warm, then heavy weights or manual presses apply pressure from above. This squeezes out remaining whey and binds the individual curds into a unified mass.

Pressure must be applied gradually, starting light and increasing over several hours. Too much pressure too quickly can cause the cheese to crack or develop texture problems.

Throughout the pressing process, the cheese makers flip the molds periodically, ensuring even compression from all sides. They unwrap the developing cheese, check for any issues, rewrap it in fresh cheesecloth, and return it to the press.

This hands-on attention catches problems early, before they can ruin an entire wheel.

The pressing stage can take anywhere from several hours to a full day, depending on the type of cheese being made. Hard cheeses need more pressing time than softer varieties.

The cheese makers track each mold carefully, knowing exactly when each one went into the press and when it needs to come out.

After pressing, the cheese moves to the aging room, a temperature and humidity-controlled space where wheels rest on wooden shelves for weeks, months, or even years. This is where good cheese becomes great cheese, as time works its subtle magic on flavor and texture.

Walking into the aging room is an overwhelming sensory experience. The smell of aging cheese fills the air, pungent but not unpleasant.

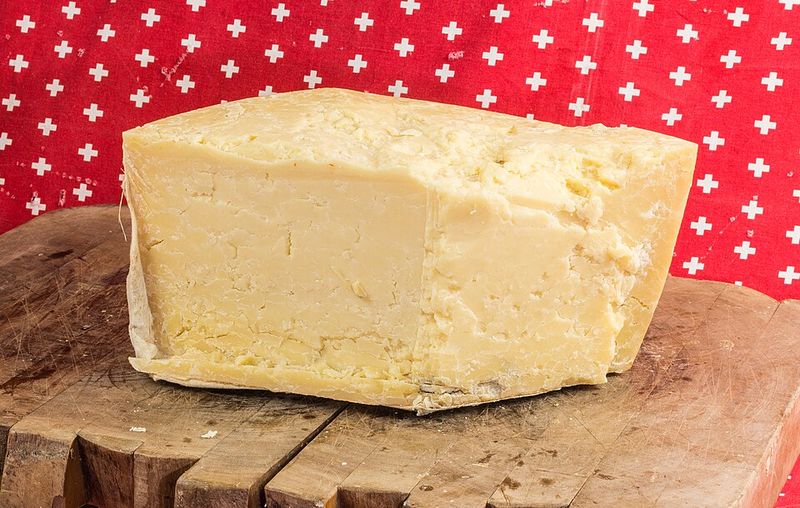

Row upon row of wheels line the shelves, each one marked with the date it was made. Some are young and pale, others have developed the deep golden color that comes with extended aging.

The cheese makers visit the aging room regularly to turn the wheels and check for any problems. Mold can develop on the surface, which is normal and actually desirable for certain varieties.

They brush off excess mold, inspect for cracks or other issues, and rotate the wheels to ensure even aging. Each wheel receives individual attention, just as it did during production.

Aging transforms cheese in ways that can’t be rushed. Young cheddar tastes mild and slightly rubbery.

After six months, it develops sharpness and complexity. At a year or more, it becomes crumbly and intensely flavored, with crystals of concentrated protein that crunch between your teeth.

Patience creates these qualities. There are no shortcuts.

No Shortcuts: Why the Slow Way Matters

Modern industrial cheesemaking has developed numerous shortcuts that speed production and reduce labor costs. Mechanical stirrers eliminate hand stirring.

Pasteurization kills bacteria, making the process more foolproof but also removing flavor complexity. Artificial additives can mimic some characteristics of aging in a fraction of the time.

The Amish cheese makers in Oklahoma reject all of these innovations. Their methods remain unchanged from those used by their ancestors, not out of stubbornness or ignorance, but because they believe the old ways produce better cheese.

Every shortcut that speeds production also compromises quality in some way.

Hand stirring allows for constant monitoring and tiny adjustments that machines can’t make. Raw milk contains beneficial bacteria that contribute to flavor depth.

Natural aging develops complexity that artificial additives can’t replicate. Each traditional step exists for a reason, contributing something essential to the final product.

This commitment to quality over efficiency means production is limited. The cheese makers can only produce so much in a day, constrained by the physical demands of their methods.

They could make more cheese and more money by modernizing, but they choose not to. Quality matters more than quantity.

The cheese matters more than the profit.

Understanding Amish cheese means understanding the Amish people who make it. Their approach to cheesemaking reflects broader values that define their entire way of life: simplicity, hard work, community, and skepticism of modern technology.

These aren’t just business principles, they’re religious convictions that shape every aspect of daily existence.

The cheese makers learned their craft through apprenticeship, working alongside experienced family members from a young age. No culinary schools, no formal certifications, just hands-on training that builds skill through repetition and practice.

By the time they take charge of their own kettles, they’ve been making cheese for years under watchful supervision.

Humility characterizes their approach. They don’t boast about their cheese or market it aggressively.

The product speaks for itself. Word of mouth brings customers from across Oklahoma and beyond, people who’ve tasted the difference and keep coming back.

The cheese makers remain focused on their work, not on self-promotion or building a brand.

Community matters deeply. Profits from the cheese operation support not just individual families but the broader Amish community.

Money earned goes toward shared expenses, helping neighbors in need, and maintaining the simple lifestyle they value. Making cheese isn’t just a job, it’s a way of serving and strengthening their community.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.