I have to be honest with you. I love Nashville, Indiana, but I also know exactly what locals mean when they roll their eyes on a busy October weekend.

The leaf-peepers pour in, the one-way loop on Van Buren Street backs up for what feels like miles, and finding a parking spot becomes a full-time job. Brown County’s little arts town has a charm that is genuinely hard to resist, and that is precisely the problem.

The same beauty that makes Nashville special is the reason it sometimes feels like it belongs more to visitors than to the people who actually call it home. If you have ever tried to grab a quick lunch on a fall Saturday and waited forty-five minutes just to turn left, you already understand every word of this article.

The One-Way Loop That Locals Dread Every Single Weekend

Ask any Nashville local what their least favorite part of living here is, and you will probably hear two words: the loop. Van Buren Street runs one-way through the heart of downtown Nashville, and on a busy fall weekend it transforms from a charming small-town road into something that resembles a parking lot with ambitions.

The congestion is not just frustrating. It is genuinely disorienting for people who just want to run a quick errand.

Brown County sees over a million visitors each year, and a significant chunk of them funnel right through that narrow corridor. Locals who need to pick up groceries or drop off a package often time their trips around tourist traffic the way city folks time trips around rush hour.

Early mornings on weekdays are golden. Saturday afternoons in October are basically off-limits.

The town of Nashville has explored traffic solutions over the years, but the physical layout of the historic district makes major road changes complicated and expensive. The one-way system was originally designed to manage flow, but it now feels like it concentrates the problem rather than solving it.

For visitors, the slow crawl can actually be a pleasant way to window-shop. For a local trying to get somewhere, it is a different story entirely.

Patience is not optional here. It is a survival skill.

Brown County State Park Draws Massive Crowds That Spill Into Town

Brown County State Park sits just outside Nashville and is the largest state park in Indiana. That distinction sounds wonderful until you realize what it means on a peak fall weekend.

The park covers over 16,000 acres of forested hills and trails, and it pulls visitors from across the Midwest like a magnet. When the parking lots fill up inside the park, those cars spill back onto State Road 46 and directly into Nashville’s already strained downtown grid.

The park is genuinely breathtaking. Trails like Hesitation Point offer sweeping views of the Brown County hills, and the horse trails and mountain bike paths attract serious outdoor enthusiasts.

Abe Martin Lodge inside the park has been a beloved gathering spot for Indiana families for decades. None of that is the problem.

The problem is sheer volume meeting limited infrastructure.

Locals who grew up hiking those trails often avoid the park entirely from mid-September through early November. They know the secret: weekday mornings in late spring or early summer offer the same gorgeous scenery with a fraction of the crowd.

Brown County State Park is located at 1405 State Road 46 West in Nashville. It is worth every step of every trail.

Just maybe not on a Sunday in October when half of Indianapolis has the same idea at the exact same moment.

The Art Colony Legacy That Accidentally Made Nashville Too Popular

Back in 1907, a group of artists discovered the rolling hills and golden light of Brown County and decided this was exactly where they needed to be. The Brown County Art Colony was born, and painters like T.C.

Steele put this quiet corner of Indiana on the cultural map. What started as an artists’ retreat gradually became a destination, and that destination eventually became a tourist economy that now defines almost everything about Nashville.

The Brown County Art Gallery on Artist Drive still showcases regional artists and carries on that original spirit beautifully. The T.C.

Steele State Historic Site at 4220 T.C. Steele Road preserves the artist’s home, studio, and gardens in a way that feels genuinely moving.

These are real cultural treasures, and locals are proud of them. The tension comes from what grew up around them.

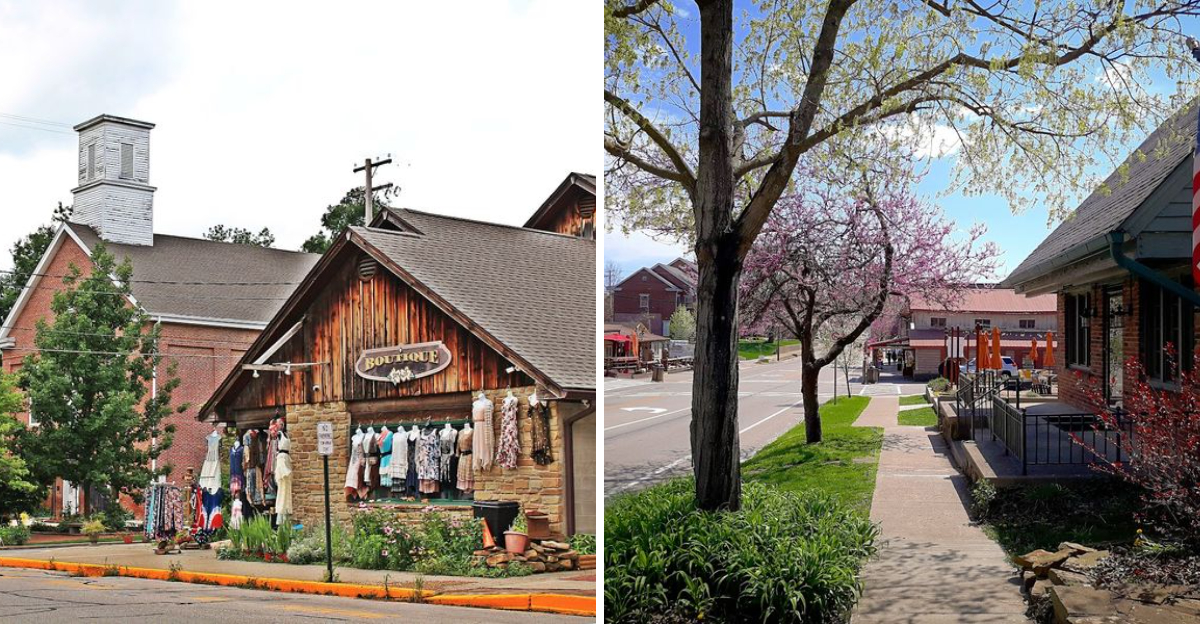

Gift shops, fudge stores, and novelty boutiques now outnumber working artist studios by a wide margin. Longtime residents remember when Nashville felt like an art town with tourists, not a tourist town with some art still hanging on the walls.

The colony’s legacy is real and worth celebrating. It is just a little hard to feel that legacy when you are stuck behind a tour bus on Franklin Street trying to find the gallery you actually came to see.

The roots are still there, though. You just have to look a little harder.

Parking Has Become a Part-Time Job for Everyone Involved

There is a running joke among Nashville locals that finding a parking spot on a fall Saturday is harder than finding a good deal at any of the shops on Main Street. It is funny because it is true.

The town was built for a different era, when visitors arrived in smaller numbers and the streets could absorb the flow without turning into gridlock. That era is long gone, and the parking situation has not kept pace with the growth.

The town has added lots over the years, and there is a free public lot near the Brown County Convention and Visitors Bureau on North Van Buren Street. Still, on peak weekends those spots vanish within an hour of the shops opening.

Visitors circle the same blocks repeatedly, contributing to the very congestion they are frustrated by. It is a cycle that feeds itself in the most maddening way possible.

Locals have developed elaborate systems. Some park at the Brown County Fairgrounds on State Road 46 East and walk in.

Others arrive before 9 in the morning and are done before the main wave hits. A few just stay home on the worst weekends and order online like the rest of modern America.

Nashville is working on long-term solutions, but any fix requires balancing the needs of a historic town with the demands of a tourism economy that now drives most of its revenue. It is a genuinely difficult puzzle with no easy answer.

Local Restaurants Struggle to Serve Neighbors When Tourists Fill Every Table

Spending years in Nashville, Indiana means you know the look on a local’s face when they walk into their favorite lunch spot and see a two-hour wait. It happens constantly from September through November, and it is one of the most quietly frustrating parts of living in a tourist town.

The restaurants here are genuinely good, and they deserve every bit of their reputation. That reputation, though, comes with a crowd that locals have to compete with just to eat lunch.

The Hob Nob Corner Restaurant at 17 West Main Street is one of the most beloved spots in town, known for hearty comfort food and a warmth that feels like eating at someone’s home. Locals love it.

Visitors love it just as much, which means the wait times on weekends can stretch far beyond what anyone planned for. Similar scenes play out at Nashville House and other long-standing spots throughout town.

Many residents have quietly shifted their dining habits to weekday evenings when the tourist tide pulls back and the town exhales a little. Some have discovered smaller, less prominent spots that have not yet made the travel blog circuit.

There is a real community of people who genuinely care about Nashville’s food scene, and they support these restaurants fiercely. They just wish they could get a table without planning it like a military operation every single weekend from Labor Day onward.

The Pioneer Village and Old Jail Remind You What Nashville Was Before the Shops

Somewhere between the fudge shops and the candle stores, there is a version of Nashville that remembers what it was before tourism became the whole point. Brown County Pioneer Village is one of the best places to feel that older, quieter identity.

The collection of restored 19th-century buildings, including The Old Log Jail, sits tucked away in a way that many visitors never even discover. That is honestly part of its charm.

The Pioneer Village is managed by the Brown County Historical Society and gives a grounded, honest look at what life in this part of Indiana actually looked like before the art colony arrived and before the leaf-peepers followed. Walking through those structures, you get a sense of the grit and simplicity that defined the region for generations.

It is a different kind of experience than browsing a gallery, and it is equally valuable.

Locals tend to have a genuine affection for this spot precisely because it does not feel like it was designed for Instagram. The Old Log Jail is small, unpolished, and quietly fascinating.

For anyone who wants to understand Nashville beyond its current tourist identity, this is where to start. The historical society works hard to preserve these structures with limited resources, and that effort deserves more recognition than it typically gets from the millions of visitors who pass through town each year without ever stopping here.

Seasonal Tourism Creates a Town That Locals Barely Recognize in October

October in Nashville, Indiana is a study in transformation. The hills surrounding town turn into something genuinely stunning, all amber and copper and deep red against a bright blue sky.

That beauty is real, and no local would deny it. But the town that emerges during peak fall season barely resembles the quiet, neighborly place that residents experience the rest of the year.

It can feel like someone replaced your hometown with a theme park version of itself.

Pop-up vendors appear. Traffic signs multiply.

Temporary staff fill shops that were quiet all summer. The sidewalks on Van Buren Street become nearly impassable on a busy Saturday, and the noise level rises to a pitch that feels foreign in a town of roughly 800 permanent residents.

Nashville’s population effectively multiplies dozens of times over during the busiest fall weekends.

The economic reality is undeniable. Tourism revenue keeps Nashville alive in ways that no one can dismiss.

Local business owners depend on those fall weeks to carry them through slower months, and that dependency shapes every decision the town makes about growth, infrastructure, and identity. Still, many longtime residents quietly grieve the Nashville they knew before it became this popular.

They are not wrong to feel that way. Loving a place and feeling displaced by its success are not mutually exclusive emotions, and Nashville locals navigate both of those feelings every single year when the leaves start to turn.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.