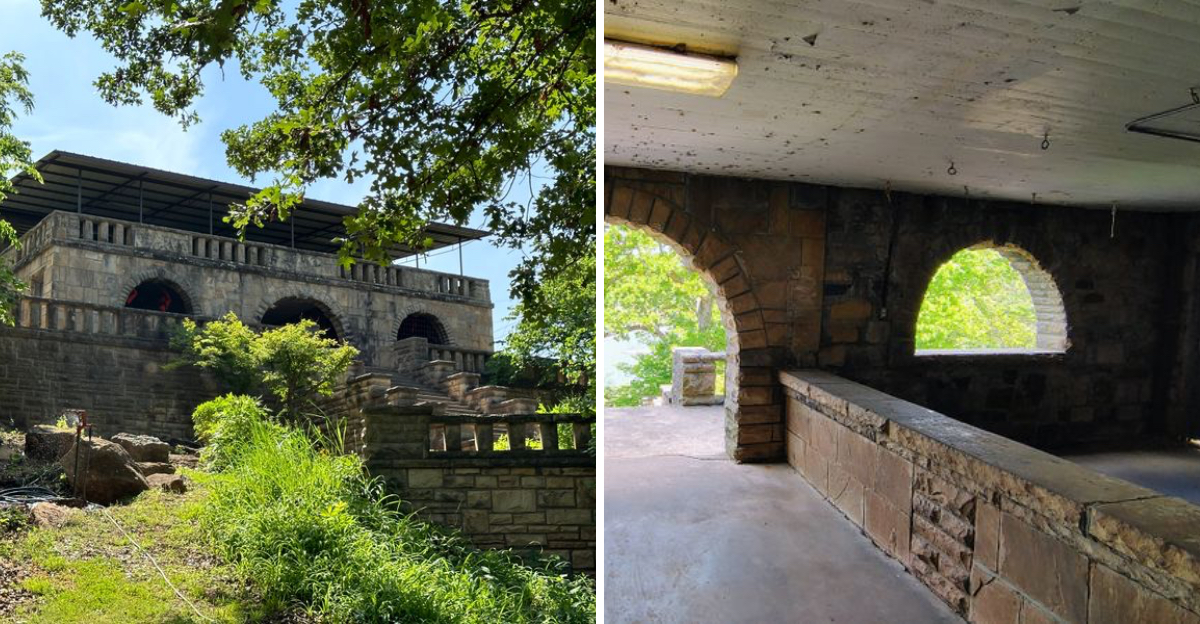

Deep in the rolling hills of northern Oklahoma sits a relic from another era, a place where stone walls meet lake water and history whispers through every archway.

The Pawnee Bathhouse, built in 1939 by the Works Progress Administration, still stands as a haunting monument to Depression-era ambition and community spirit.

While it functions as a summer swimming spot today, there’s something about this place that catches you off guard, especially when shadows stretch long across those weathered stone steps and the water goes still as glass.

Whether you’re drawn by the eerie beauty of its architecture or the strange pull of its past, this forgotten bathhouse offers an experience that lingers long after you’ve climbed back up those endless stairs and driven away.

The WPA Architecture That Time Forgot

Stone by stone, the Works Progress Administration crew built this bathhouse during the Great Depression, carving out a piece of history that would outlast almost everything from that era.

The curved arches and native stone walls create an atmosphere that feels both grand and ghostly, like stumbling upon ancient ruins in the Oklahoma prairie.

Walking through the structure feels like stepping into a time capsule where the 1930s never quite let go. The craftsmanship shows in every detail, from the carefully laid stonework to the sweeping staircases that descend toward the water.

These weren’t just construction workers slapping together a swimming hole. They were artisans creating something meant to endure.

Yet there’s an unsettling quality to all that permanence. The building stands too perfect, too preserved in some ways, while showing decay in others.

Shadows pool in corners where sunlight can’t quite reach, and the echo of footsteps on stone creates sounds that seem to come from nowhere and everywhere at once.

Visitors often comment on the beauty first, then the strangeness. Something about the proportions feels off, like the place was built for a different kind of gathering than what happens now.

The empty spaces seem to wait for crowds that no longer come, at least not in the numbers they once did.

The Staircase Descent Into Uncertainty

Count them if you dare, but the stairs leading down to the swimming area seem to multiply as you descend. Multiple flights of wide stone steps wind through the bathhouse structure, each turn revealing another set below.

No handrails line the sides, just open space and the distant shimmer of water waiting at the bottom.

Families with small children navigate these steps carefully, and older visitors sometimes take the alternative access road rather than risk the climb. The stairs themselves are beautiful in a stark way, worn smooth by decades of bare feet and summer traffic.

But there’s something disorienting about the descent, especially when you’re alone.

The way sound travels on these staircases adds to the unease. Voices from above seem closer than they should be, while the water below sounds impossibly far away.

The stone amplifies every footfall, creating rhythms that don’t quite match your pace.

Coming back up after a swim proves even more challenging. Your legs already tired from swimming, the stairs seem steeper, longer, more numerous than they did on the way down.

Some visitors swear the climb takes twice as long, though the physics shouldn’t work that way. The afternoon sun beats down on the stone, creating heat waves that make the top shimmer like a mirage you’re not sure you’ll reach.

The Lake That Changes Temperature Without Warning

Wade into the roped-off swimming area and you’ll notice something odd right away. The water temperature shifts dramatically without warning, warm near the surface and suddenly ice cold just a few feet down.

There’s no gradual change, just distinct layers of temperature that feel unnatural, almost intentional.

Swimmers describe the sensation as unsettling, like invisible hands pulling you down into colder depths. The lake bottom drops off quickly in places, and the murky water makes it impossible to see what’s below your feet.

Several reviews mention losing goggles and glasses in the cloudy water, the items vanishing into depths that seem to swallow things whole.

The swimming area includes platforms and diving boards that extend over deeper water. Standing on these structures, looking down into the opaque lake, creates a feeling of vertigo.

You can’t see the bottom, can’t gauge the depth, can’t know what might be swimming beneath you.

Local stories mention water snakes spotted near the bathhouse, though officials downplay these reports. Still, the idea lingers in your mind as you swim, every brush of lake grass against your leg feeling like something more sinister.

The water itself seems to hold secrets, refusing to reveal what lies beneath its murky surface even on the brightest summer days.

The Empty Changing Rooms That Echo

Step into the old changing rooms and bathrooms, and you’ll find facilities that work but feel frozen in another decade. The showers run, the toilets flush, but something about these spaces feels perpetually abandoned even when people are using them.

One review mentions bathroom stalls with curtains instead of proper doors, a detail that adds to the general sense of exposure and vulnerability.

The stone walls in these interior spaces create acoustics that amplify every sound. Water dripping becomes a percussion that follows you through the rooms.

Your own breathing seems louder than it should be. Conversations from outside filter in strangely, words distorted by the way sound bounces off stone and water.

There’s a coldness to these rooms that persists even on hot summer days. The stone holds onto cooler temperatures, creating a clammy atmosphere that raises goosebumps on wet skin.

The lighting, when it works, casts shadows that seem too dark for the fixtures’ brightness.

Visitors often hurry through these spaces, changing quickly and moving back outside where the openness feels safer. Something about being enclosed in those stone chambers, with their echoes and their chill, makes people uncomfortable in ways they can’t quite articulate.

The rooms serve their function, but they don’t invite lingering.

The Season When Everything Closes Down

The bathhouse operates only during summer months, opening at noon and closing at six daily when weather permits. But visit during the off-season, and you’ll find a completely different atmosphere.

The place becomes truly abandoned then, with no lifeguards, no families, no sounds except wind and water and the occasional animal call.

One review describes visiting in early May and having the entire place to themselves. The beauty remains, but without the summer crowds, the isolation becomes overwhelming.

Walking the grounds alone, you realize how remote this place actually is, how cut off from the modern world it feels.

The stone structure looks even more ancient when empty. Moss grows in cracks, leaves pile in corners, and the whole complex takes on the appearance of genuine ruins rather than a functioning facility.

The swimming area sits undisturbed, the water dark and still as a mirror reflecting nothing but sky and stone.

There’s a melancholy to the closed bathhouse that hits differently than summer eeriness. This is a place built for community, for gathering, for the sounds of children playing and families picnicking.

Without those purposes being fulfilled, it feels purposeless, a monument to intentions that no longer matter. The emptiness becomes almost physical, a presence you can feel pressing against you as you walk through spaces meant to hold hundreds but occupied only by ghosts and memories.

The Affordable Admission That Feels Like a Warning

Entry costs just a few dollars, cash only, collected at the gate when the facility is open. The price seems almost suspiciously low, like the place is trying too hard to attract visitors.

In an era when everything costs more, this throwback pricing adds to the feeling that time works differently here.

The cash-only policy means no digital trail, no credit card record of your visit. You pay your money, you enter, and when you leave, there’s no proof you were ever there except your own memory and perhaps a few photos.

Something about that anonymity feels both freeing and slightly ominous.

The minimal cost also means minimal amenities. What you see is what you get, no fancy additions or modern upgrades beyond basic safety requirements.

The bathhouse exists in a state of benign neglect, maintained just enough to stay open but not enough to lose its Depression-era character.

Small snacks and drinks are available for purchase, also cash only, at nominal prices that seem pulled from decades past. The whole economic model of the place feels unsustainable, like it exists outside normal financial realities.

You hand over your bills and wonder how they keep the lights on, how they pay the lifeguards, how this relic continues operating when so many similar places have closed and crumbled into true ruins.

The Lifeguards Who Seem Too Young for the Responsibility

Reviews consistently mention friendly, helpful lifeguards on duty during operating hours. But there’s something jarring about seeing teenagers in charge of safety at a place with this much history and these many hazards.

The broken dock boards, the deep water, the stairs without handrails, all create scenarios that seem to require more experience than summer job training provides.

The lifeguards sit in their stations, watching the water with the vigilance their job requires. But you can’t help wondering what they think about during slow hours, whether they know the stories about this place, whether they feel the same unease that visitors describe.

Do they notice the cold spots in the water, the way sounds echo strangely, the sensation of being watched from the tree line?

Their presence provides reassurance, proof that someone is paying attention, that help exists if something goes wrong. Yet it also highlights the dangers, the need for constant supervision in an environment that seems benign but hides risks beneath its murky surface.

As closing time approaches and the last swimmers leave the water, you wonder what the lifeguards do in those final minutes. Do they linger, cleaning up and securing the facility?

Or do they leave quickly, eager to escape before the sun sets completely and the wildlife emerges and the bathhouse returns to whatever state it occupies when humans aren’t there to observe it?

The Garden Areas That Bloom in Unexpected Places

Landscaped areas surround parts of the bathhouse, gardens that somehow thrive despite the general atmosphere of decay and abandonment. Flowers bloom in season, creating pockets of color and life that contrast sharply with the stern stone architecture.

Reviews mention these pretty areas, though often in passing, as if the beauty is almost suspicious.

Gardens require maintenance, someone’s care and attention to flourish. Yet the bathhouse operates on such a minimal budget with such limited staff that you wonder who tends these plants.

Do volunteers come in the early morning, working before the facility opens? Or do the gardens simply persist through some combination of good soil and Oklahoma weather, thriving despite rather than because of human intervention?

Walking through these cultivated spaces creates cognitive dissonance. The flowers and shrubs suggest care, attention, a desire to make the place welcoming.

But the crumbling dock, the broken boards, the curtains instead of stall doors all suggest neglect. The contrast between what’s maintained and what’s ignored feels arbitrary, chosen by criteria that don’t quite make sense.

Visitors mention enjoying the scenic walk around the grounds, the nature trails that extend beyond the swimming area. These paths wind through woods and along the shoreline, offering views that are genuinely beautiful.

Yet even here, surrounded by blooming gardens and natural splendor, that underlying unease persists, as if the prettiness is a mask over something the place doesn’t want you to see.

The Private Events That Close Public Access

Sometimes the bathhouse hosts private events, weddings and gatherings that close the facility to regular visitors. Reviews mention driving up only to find the place unavailable, reserved for celebrations that seem incongruous with the location’s unsettling atmosphere.

Who chooses this spot for their wedding, and what kind of photos do they take against the backdrop of Depression-era stone and murky lake water?

The idea of celebration here feels forced, like trying to impose joy on a space that resists such emotions. Yet people do it, booking the bathhouse for their special occasions, apparently seeing beauty where others see eeriness.

Maybe in their eyes, the historic architecture provides character, the lake offers scenic views, and the whole package creates memorable experiences for all the right reasons.

One particularly telling review describes a visitor’s experience improving dramatically after city council intervention regarding rental policies. The fact that officials needed to get involved suggests tensions between public access and private use, between the bathhouse as community resource and event venue.

These competing purposes create another layer of strangeness to the place’s identity.

When you visit during public hours, you might wonder about the ghosts of recent celebrations. Did a bride descend those endless stairs in her white dress?

Did wedding guests swim in that murky water? The mental images don’t quite compute, adding yet another element of surrealism to a location already thick with contradictions and unease.

The Accessibility That Comes With Compromise

An alternative entrance exists for those unable to navigate the many stairs, a small access road that winds around to parking near the beach area. This accommodation shows thoughtfulness, an awareness that the bathhouse’s dramatic architecture creates barriers for some visitors.

Yet the limited parking at this accessible entrance reveals the compromise inherent in the solution.

Arriving through the back entrance means missing the full experience of the bathhouse, skipping the descent through stone archways and down those endless steps. You gain access to the water but lose the journey, the gradual transition from upper world to lower realm that the stairs provide.

It’s practical but incomplete, like reading a summary instead of the full story.

The existence of this workaround also highlights the bathhouse’s fundamental design flaw. The WPA builders created something beautiful but not universally accessible, prioritizing aesthetics over accommodation.

Modern adjustments try to correct this, but the fixes feel grafted on, afterthoughts that don’t quite integrate with the original vision.

Still, the effort matters. Families with elderly members or individuals with mobility challenges can still enjoy the lake, still participate in this strange slice of Oklahoma history.

They arrive by a different path, but they arrive nonetheless, joining the swimmers and sunbathers who descended the stairs. Once everyone reaches the water, the method of arrival becomes irrelevant, and the shared experience of this unsettling place binds all visitors together regardless of how they got there.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.