Georgia’s Southern charm has long been a beacon for travelers seeking authentic hospitality, rich history, and moss-draped landscapes that whisper stories of the Old South.

But as tourism has grown over the decades, the state’s character has shifted in ways both visible and invisible, transforming how communities live, work, and welcome outsiders.

From bustling Savannah streets once reserved for locals to mountain towns now catering to weekend visitors, the relationship between Georgians and their guests has become more complex.

This journey through ten Georgia destinations reveals how tourism has quietly rewritten the script of Southern life, for better and sometimes for worse.

Savannah’s Historic District

Walking through Savannah’s Historic District today feels like stepping onto a movie set, and that’s no accident.

The neighborhood’s antebellum mansions and cobblestone squares have become so iconic that they attract millions of visitors annually, fundamentally changing how residents experience their own city.

What was once a living, breathing community of families who had occupied these homes for generations has transformed into a museum-like district where tour groups outnumber locals on many blocks.

Privacy has become a luxury many longtime residents can no longer afford.

Tourists photograph doorways, peek into windows, and pose on front steps without realizing families are trying to live normal lives inside.

The First African Baptist Church, a sacred space with profound historical significance as the oldest Black church in North America, now balances its spiritual mission with managing constant visitor requests.

Local businesses have adapted by shifting their focus from serving neighbors to entertaining guests.

Family-run restaurants that once offered simple Southern cooking have either closed or reinvented themselves as themed experiences with souvenir shops attached.

Rising commercial rents driven by tourism demand have priced out establishments that couldn’t pivot quickly enough.

Even the famous squares, designed by James Oglethorpe as communal gathering spaces, now function primarily as waypoints on guided tours rather than places where neighbors meet.

The architectural preservation that tourism revenue enabled has been a blessing, saving countless historic structures from demolition.

Yet the soul of the neighborhood has shifted, trading everyday authenticity for carefully curated charm that exists primarily for outsiders to consume and photograph.

St. Simons Island

St. Simons Island once represented the quintessential Georgia coastal retreat where families returned generation after generation to the same modest beach cottages.

The rhythm of island life moved slowly, dictated by tides and seasons rather than checkout times and reservation calendars.

Neighbors knew each other by name, and the island’s few restaurants served locals as reliably as they served the occasional visitor.

Tourism’s explosion over recent decades has redrawn this landscape entirely.

Those cherished family cottages have largely disappeared, replaced by luxury vacation rentals and resort-style developments that command premium prices during peak seasons.

Property values have skyrocketed, making it nearly impossible for working families to purchase homes here anymore.

The island’s character shifts dramatically with the tourist calendar now.

Summer weekends bring traffic jams to roads that were designed for a much smaller population, and beaches that once felt spacious now require early arrival to claim a decent spot.

Local shops have increasingly stocked their shelves with resort wear and souvenirs rather than the everyday goods island residents actually need.

Restaurant menus have grown more ambitious and expensive, pricing out many locals who once considered these establishments their regular haunts.

The lighthouse, long a beloved community landmark, now primarily serves as a photo opportunity for visitors rather than a functional beacon for the island’s maritime community.

Year-round residents often feel like strangers in their own home during tourist season, waiting for fall to reclaim some semblance of the quieter island they remember.

Helen’s Alpine Village

In the 1960s, Helen was a struggling logging town facing economic collapse as the timber industry declined.

Business owners made a bold decision to completely reinvent their town’s identity, transforming it into a Bavarian alpine village that had absolutely no historical connection to German culture.

This manufactured charm proved wildly successful, drawing tourists by the thousands who wanted to experience a slice of Bavaria without leaving Georgia.

The transformation required every building in the commercial district to adopt alpine architecture, complete with timber framing, flower boxes, and painted murals.

What emerged was a theme park version of Southern charm, where authenticity took a backseat to commercial appeal.

Helen’s year-round Oktoberfest celebrations and Christmas markets now define the town’s identity far more than any actual Georgian heritage.

Local residents have become performers in this ongoing production, many working in shops selling German imports or serving schnitzel in restaurants decorated with Bavarian flags.

The economic benefits have been undeniable, rescuing Helen from certain decline and providing jobs for surrounding communities.

However, the cost has been the erasure of the town’s genuine Appalachian roots and timber industry history.

Children growing up in modern Helen learn more about German traditions than about their own ancestors who logged these mountains.

The Chattahoochee River running through town now primarily serves tubing tourists rather than the fishing and swimming locals once enjoyed without crowds.

Helen represents tourism’s most dramatic rewriting of Southern identity, proving that economic survival sometimes requires communities to become something entirely different from what they were.

Jekyll Island’s Historic District

Jekyll Island carries a unique history as the former private playground of America’s wealthiest families, including the Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, and Morgans.

The Jekyll Island Club once represented the ultimate in exclusive Southern coastal living, where the nation’s elite escaped northern winters in elegant seclusion.

When the state of Georgia purchased the island in 1947, the vision was to create a public retreat accessible to all Georgians, democratizing what had been intensely private.

Tourism development has honored this democratic ideal in some ways while compromising it in others.

The restored historic cottages now operate as museums and a luxury hotel, allowing visitors to experience the opulence that was once reserved for the ultra-rich.

This preservation effort has been remarkable, protecting architectural treasures that might otherwise have deteriorated beyond repair.

But the island’s character has shifted from a quiet state park to a bustling resort destination with golf courses, beach clubs, and convention facilities.

Development restrictions meant to protect the island’s natural beauty are constantly tested by pressure to expand tourist amenities and increase revenue.

Wildlife habitats that once covered much of the island have shrunk as infrastructure expanded to accommodate more visitors.

The beaches, while still beautiful, now see summer crowds that would have shocked the island’s original elite residents who valued privacy above all.

Local conservationists worry that each new hotel or attraction chips away at what makes Jekyll Island special.

The delicate balance between public access and preservation remains Jekyll Island’s central challenge as tourism continues reshaping this historic landscape.

Madison’s Antebellum Trail

Madison earned its reputation as the town Sherman refused to burn during his March to the Sea, preserving an extraordinary collection of antebellum architecture.

For generations, these grand homes simply housed Madison families who maintained them as private residences, unaware their town would become a major tourist draw.

The designation as part of Georgia’s Antebellum Trail transformed Madison from a quiet county seat into a weekend destination for history enthusiasts and architecture lovers.

Homeowners in the historic district now navigate the complex reality of living in houses that strangers feel entitled to photograph and discuss.

Tour buses roll through neighborhoods regularly, guides pointing out architectural details while residents try to enjoy their morning coffee in peace.

Some homeowners have embraced this attention, opening their properties for paid tours during peak seasons and special events.

Others resent the loss of privacy and the pressure to maintain their homes to tourist-worthy standards rather than simply living comfortably.

The town’s commercial district has evolved to serve visitors first and residents second, with antique shops and boutiques replacing hardware stores and everyday services.

Madison’s restaurants now offer upscale Southern cuisine for tourists rather than the simple meat-and-three plates locals prefer.

The economic boost from tourism has funded infrastructure improvements and historic preservation efforts that benefit everyone.

Yet longtime residents sometimes feel like supporting characters in a story being written primarily for outsiders.

Madison’s challenge remains honoring its remarkable history while maintaining a living community rather than becoming an outdoor museum where actual Southerners happen to reside.

Blue Ridge’s Downtown Square

Blue Ridge spent most of the 20th century as a quiet Appalachian town where locals worked in timber, mining, or agriculture without much thought to attracting outsiders.

The downtown square served as a genuine community gathering place where neighbors caught up on news and conducted everyday business.

Everything changed when developers recognized the town’s potential as a mountain getaway for Atlanta residents seeking weekend escapes.

The Blue Ridge Scenic Railway, once a working transportation line, reinvented itself as a tourist attraction offering scenic rides through the Appalachian foothills.

This single attraction catalyzed Blue Ridge’s transformation into a tourism-dependent economy.

Downtown buildings that once housed feed stores and practical businesses now contain wine-tasting rooms, art galleries, and boutiques selling mountain-themed home decor.

Property values have climbed so steeply that many longtime residents have sold their family land to developers, moving to more affordable areas as their hometown became too expensive.

The town square, while more prosperous and prettier than before, has lost much of its function as a local gathering place.

Weekends bring traffic congestion that tests the patience of residents who simply need to run errands.

Local teenagers who once hung out downtown now avoid it during tourist season, feeling out of place among the visitors.

The Appalachian culture that defined Blue Ridge for generations has been packaged and commercialized, with mountain heritage reduced to aesthetic elements that appeal to tourists.

Blue Ridge’s experience shows how tourism can bring prosperity while simultaneously displacing the very communities and cultures that made a place attractive in the first place.

Tybee Island’s Beach Culture

Tybee Island has always been Savannah’s beach, but its character has shifted dramatically from a quirky, laid-back community to a busy beach resort.

Old-time Tybee was wonderfully eccentric, with ramshackle beach houses, local dive bars, and a population that valued character over polish.

The island attracted artists, musicians, and free spirits who appreciated affordable coastal living and didn’t mind the island’s rough edges.

Tourism’s intensification has smoothed away much of that authentic weirdness.

Beach houses have been torn down and replaced with vacation rental properties designed to maximize occupancy and rental income rather than charm.

The island’s few remaining dive bars now compete with trendy restaurants and beach clubs that cater to day-trippers from Savannah and beyond.

Summer weekends bring such crowds that parking becomes nearly impossible, and the beach feels more like an urban pool than a coastal retreat.

Local environmental concerns have grown as increased foot traffic damages dune systems and disturbs nesting sea turtles.

The island’s year-round residents, many of whom work in Savannah’s tourism industry themselves, feel increasingly squeezed by rising costs and diminishing community space.

Neighborhood spots where locals once gathered have either closed or transformed into tourist-oriented businesses with higher prices and different atmospheres.

Tybee’s annual events, like the Beach Bum Parade, have grown from intimate local celebrations into major tourist draws that strain the island’s infrastructure.

The tension between preserving Tybee’s funky beach-town soul and capitalizing on tourism dollars remains unresolved, with each season bringing the question closer to a tipping point.

Dahlonega’s Gold Rush Heritage

America’s first major gold rush happened right here in Dahlonega decades before anyone struck gold in California.

This remarkable history shaped the town’s identity for generations, with families passing down stories of the 1828 discovery and the boom times that followed.

For most of the 20th century, Dahlonega remained a modest mountain town where gold rush history was simply part of the local fabric rather than a marketing tool.

Tourism discovered Dahlonega’s potential relatively recently, recognizing that visitors would pay to experience gold panning and explore mining history.

The town square, anchored by the historic courthouse topped with real gold leaf, became the centerpiece of a carefully cultivated tourist district.

Businesses quickly adapted, with many offering gold panning experiences, mining-themed merchandise, and historical tours that blend fact with entertainment.

The University of North Georgia, a longstanding community institution, now shares the town with weekend visitors who sometimes outnumber students and residents combined.

Dahlonega’s wine industry, a more recent development, has added another tourism layer with tasting rooms and vineyard tours drawing different crowds than the gold rush attractions.

Local residents appreciate the economic vitality tourism brings but worry about the commercialization of their genuine historical heritage.

The gold rush story has been simplified and sanitized for tourist consumption, glossing over the complex reality of how gold fever displaced Cherokee communities from their ancestral lands.

Downtown property owners face pressure to maintain period-appropriate facades while running modern businesses, creating a stage-set quality to the historic district.

Dahlonega shows how tourism can preserve historical awareness while simultaneously flattening complex histories into easily digestible narratives that fit neatly into weekend getaway itineraries.

Stone Mountain Park

Stone Mountain has always been Georgia’s most controversial tourist attraction, and tourism itself has shaped how the state grapples with its Confederate monument problem.

The massive carving of Confederate leaders on the mountain’s face was completed in 1972, transforming a natural wonder into a political statement.

For decades, the park marketed itself around this Confederate imagery, hosting laser shows that celebrated the Old South and selling souvenirs featuring rebel flags.

This approach attracted certain visitors while making many Georgians, particularly Black residents, feel unwelcome at what was supposed to be a state park for everyone.

Tourism’s evolution and changing social attitudes have forced Stone Mountain to reconsider its identity in recent years.

The park has gradually de-emphasized Confederate symbolism in its marketing, focusing instead on natural beauty, recreational activities, and family attractions.

Laser shows now feature less Lost Cause mythology and more generic patriotic themes, though the carving itself remains unchanged and unchangeable.

This awkward transition reflects Georgia’s broader struggle with how to acknowledge difficult history without celebrating it.

Many visitors now come primarily for the hiking trails, scenic railroad, and seasonal festivals rather than the Confederate monument.

Yet the carving’s presence continues to spark debate about whether the park can ever truly move past its problematic legacy.

Tourism revenue considerations complicate every decision about Stone Mountain’s future, as the park generates significant income for Georgia.

The situation demonstrates how tourism doesn’t just respond to Southern culture but actively shapes how communities remember, present, and sometimes revise their own histories to remain economically viable and socially relevant.

Athens’ Music Scene and College Town Culture

Athens built its reputation as a legendary music town organically, with local venues nurturing bands like R.E.M. and the B-52s in intimate settings where musicians and audiences connected authentically.

The music scene emerged from genuine community creativity rather than any planned tourism strategy, making Athens feel special to those who discovered it.

As Athens’ musical legacy became nationally recognized, tourism began reshaping the very culture that made the town famous.

Historic venues that once booked unknown local bands now prioritize touring acts that draw larger, paying crowds including visitors specifically traveling to experience Athens’ music heritage.

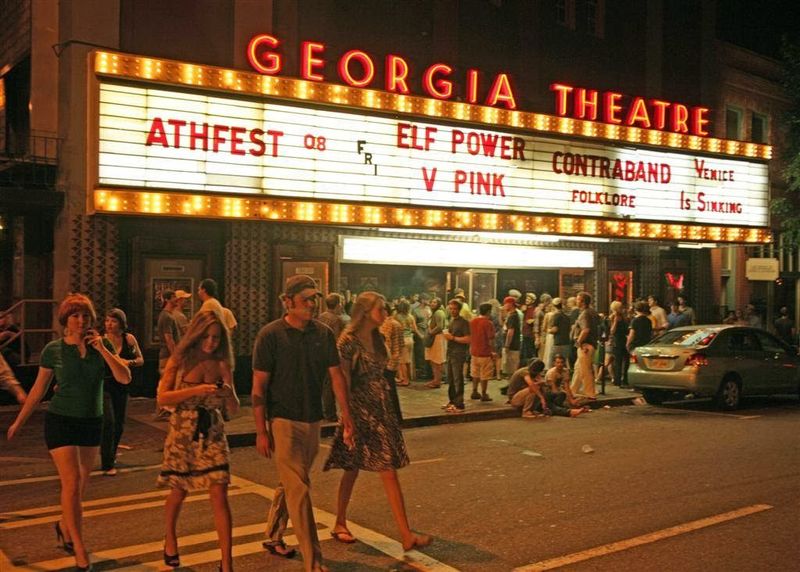

The 40 Watt Club and Georgia Theatre, while still operating, have become more professional and less scrappy, losing some of the experimental edge that defined early Athens music.

Rising rents in downtown Athens, driven partly by tourism development, have pushed out the affordable spaces where young musicians once lived and practiced.

The University of Georgia’s presence adds another layer, with college town culture now catering as much to visiting parents and football fans as to students themselves.

Game day weekends transform Athens into a massive tourist event that bears little resemblance to the town’s everyday character.

Local restaurants and bars that once served students and townspeople year-round now depend heavily on football season revenue, adjusting their offerings accordingly.

The music heritage that emerged from Athens’ authentic creative community has been packaged into walking tours and museum exhibits that feel removed from the living, breathing music scene.

Young musicians still come to Athens hoping to capture that original magic, but they find a town where the economics of tourism and college football have made it harder to maintain the affordable, experimental lifestyle that once made musical innovation possible.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.