I wasn’t sure what to expect when I first heard about Confederate Memorial Plaza in Anderson, Texas. The name alone carries weight, the kind that makes you pause and wonder what you’ll find when you arrive.

Driving up Loop 429, I noticed how quiet the area was, almost peaceful, which felt strange given all the heated conversations this place continues to spark. The monument stands as a reminder of a complicated past, one that people still can’t quite agree on how to handle.

Some see it as honoring local history and sacrifice, while others view it as a symbol that belongs in a museum, not on public display.

What struck me most was realizing that in 2026, we’re still wrestling with these same questions about memory, heritage, and how we choose to remember difficult chapters of our story.

A Monument That Refuses to Fade from Memory

Standing in front of the memorial for the first time, I felt the weight of history pressing down in a way that photographs never quite capture. The structure itself is modest compared to some monuments, but its presence feels larger than its physical dimensions.

Local residents have strong feelings about it, and those feelings haven’t softened with time.

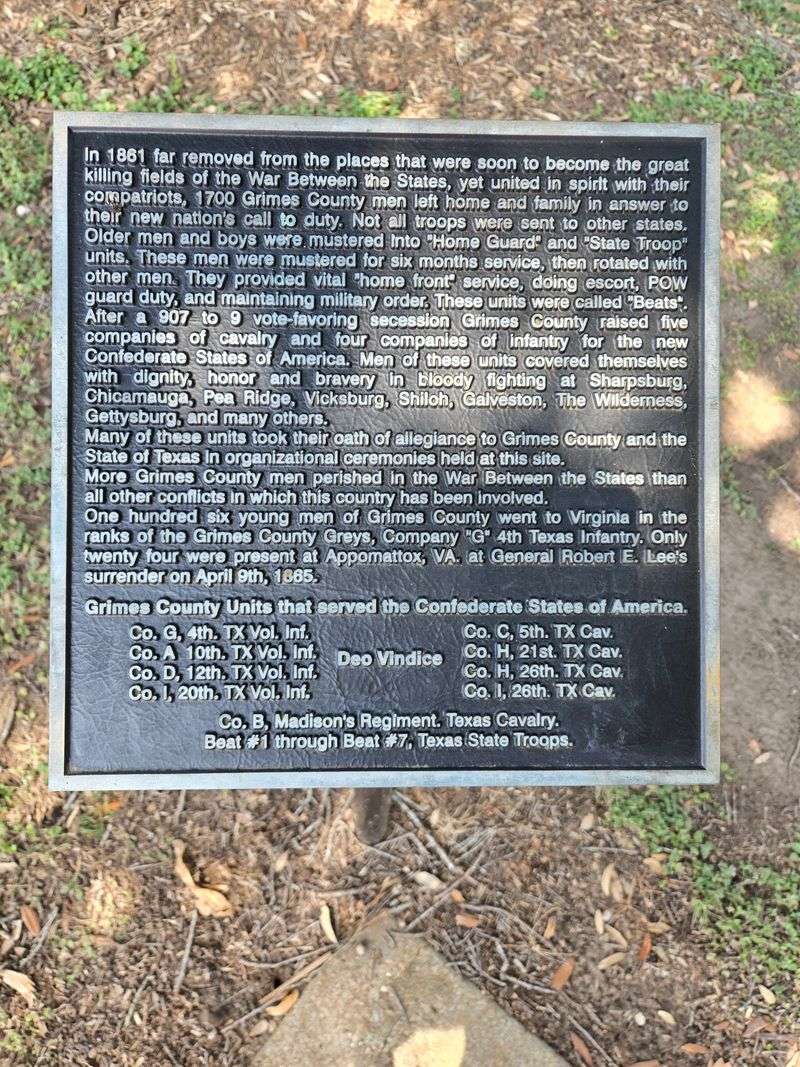

What makes this memorial different from many others is its location in Grimes County, a rural area where community ties run deep and family histories stretch back generations. The men commemorated here weren’t famous generals or politicians.

They were farmers, shopkeepers, and young men who left their homes during the Civil War. Many never returned, and their graves remain scattered and unmarked across distant battlefields.

The controversy isn’t about whether these men existed or whether their families grieved. Everyone agrees on those facts.

The debate centers on what this memorial represents in a broader sense. Does it honor individual sacrifice, or does it glorify a cause built on oppression?

That question has no easy answer, and standing there, I understood why people on both sides feel so passionately about their positions.

Why This Small Town Memorial Draws National Attention

Anderson isn’t a place most people have heard of unless they live nearby. The town has fewer than 300 residents, and you could drive through it in about two minutes if you didn’t stop.

Yet this tiny community finds itself at the center of a debate that extends far beyond Texas borders. News outlets have covered the memorial, online forums argue about it, and people who’ve never set foot in Grimes County have strong opinions about what should happen to it.

The attention feels disproportionate to the size of the place, but that’s exactly what makes it significant. Small towns across America face similar questions about Confederate monuments, and Anderson has become a case study.

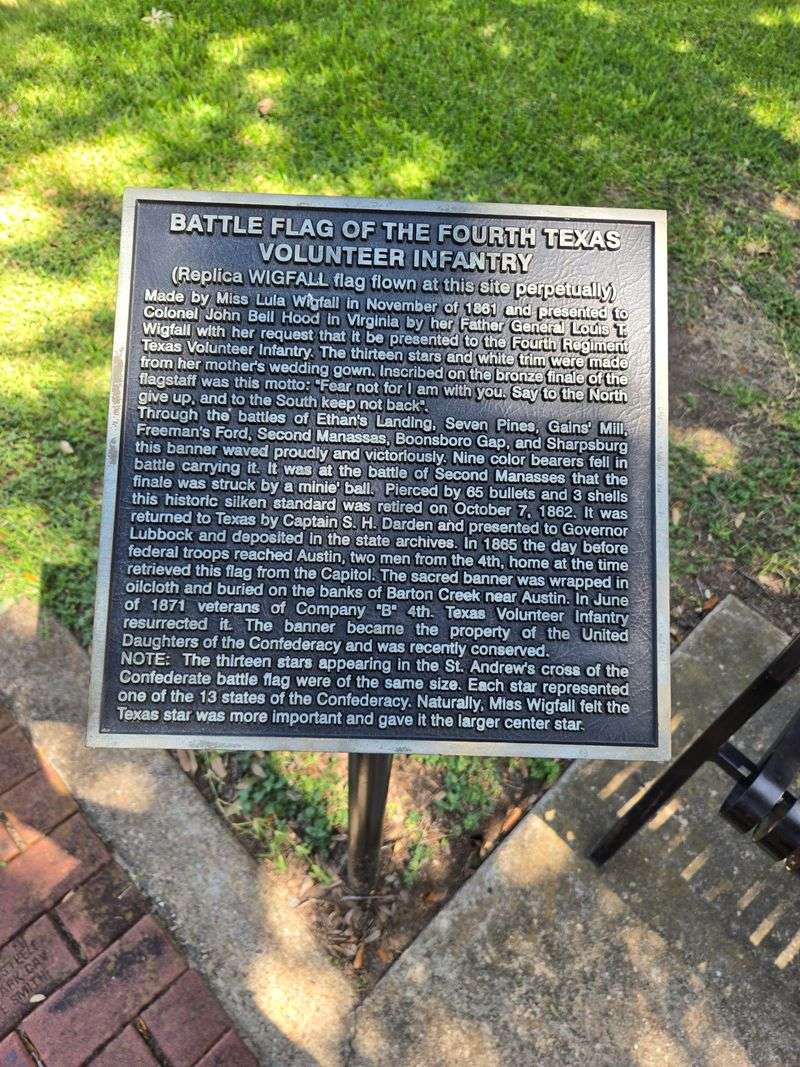

Should communities remove these memorials, add context through additional plaques, or leave them untouched as historical markers? Each option satisfies some people while upsetting others.

Walking around Anderson, I noticed how the memorial sits quietly while the world debates its fate. Local businesses operate nearby, residents go about their daily routines, and life continues.

The monument has become something larger than itself, a symbol in a national conversation about how we reckon with uncomfortable parts of our past.

The Men Behind the Names on the Stone

Reading the names carved into the memorial, I tried to imagine who these men were before the war. They had families, dreams, daily worries about crops or weather or making ends meet.

Then came the call to serve, and they left behind everything familiar. Some were barely old enough to shave, while others had children of their own waiting at home.

Historical records show that Grimes County sent hundreds of men to fight for the Confederacy. Disease killed more of them than bullets did, a grim reality of 19th-century warfare that people often forget.

Those who survived faced long marches home through a defeated South, returning to farms that had fallen into disrepair and communities forever changed. The ones who didn’t make it back were buried wherever they fell, often in mass graves without markers.

For their descendants, this memorial serves as the only gravestone many of these men will ever have. That personal connection makes the debate more complicated.

It’s easier to discuss removing a monument when it’s abstract, harder when it represents your great-great-grandfather who never came home.

Understanding this doesn’t resolve the controversy, but it adds layers to a conversation that often gets reduced to simple talking points.

What Supporters Say About Preserving History

Talking with people who want the memorial to remain, I heard consistent themes about heritage and remembrance. They argue that removing monuments erases history rather than confronting it.

One person I spoke with had ancestors who fought in the war, and for them, the memorial represents family sacrifice, not political ideology. They see it as honoring individuals who answered their state’s call, regardless of the cause they served.

Supporters often point out that these soldiers didn’t create the system of slavery or start the war. They were ordinary people caught up in extraordinary circumstances, fighting for reasons that varied from person to person.

Some believed in states’ rights, others were conscripted and had no choice, and many simply followed their communities into battle. The memorial, in this view, commemorates their courage and suffering without endorsing the Confederacy’s political goals.

This perspective emphasizes the importance of tangible connections to the past. Books and museums serve different purposes than monuments in the places where events actually occurred.

Standing where your ancestors stood creates a link across generations that feels personal and real.

For supporters, removing the memorial would sever that connection and dishonor the memory of men who deserve to be remembered as human beings, not political symbols.

Why Critics Believe the Monument Should Come Down

Those who oppose the memorial make equally compelling arguments rooted in how public spaces reflect community values. They point out that most Confederate monuments weren’t erected immediately after the Civil War but during the Jim Crow era and the Civil Rights movement.

The timing wasn’t coincidental. These monuments served as statements of white supremacy, reminders of who held power during periods when Black Americans fought for basic rights.

Critics emphasize that honoring Confederate soldiers in public spaces is fundamentally different from remembering them in private or educational settings. A monument on public land carries an implicit endorsement from the community.

It says, “These people and what they fought for deserve honor.” When the cause was preserving slavery, that message becomes deeply problematic, regardless of individual soldiers’ motivations or characters.

Many people who want the memorial removed don’t advocate for erasing history. Instead, they suggest museums or historical parks as more appropriate locations where context can be provided.

A museum can explain the complexity of the Civil War, the horror of slavery, and the experiences of soldiers without appearing to celebrate the Confederacy.

Public monuments, by their nature, honor rather than educate, and that distinction matters to those who find Confederate memorials offensive and harmful.

How Other Texas Towns Have Handled Similar Monuments

Texas has more Confederate monuments than almost any other state, and communities have taken different approaches to dealing with them. Some cities removed monuments quickly after the 2020 protests, while others added contextual plaques explaining the full history.

A few have relocated monuments to cemeteries or museums, trying to find middle ground that respects both heritage concerns and calls for change.

Dallas removed a prominent Confederate statue from a city park, and Austin took down similar monuments from its downtown area. These decisions came after years of debate, public hearings, and sometimes court battles.

Smaller towns face different pressures than big cities, where diverse populations often support removal more strongly. Rural areas tend to have deeper ancestral ties to the Confederacy, making these decisions more personally fraught.

What’s happening in Anderson reflects a broader pattern across the South and border states. Communities are grappling with how to honor their ancestors without appearing to endorse slavery or white supremacy.

Some have found creative solutions, like adding monuments to enslaved people nearby or creating historical trails that tell multiple stories. Others remain locked in debate, unable to find consensus.

The memorial in Grimes County stands as one of many still waiting for resolution in a conversation that shows no signs of ending.

The Legal and Political Battles Over Confederate Symbols

Texas law actually makes removing Confederate monuments more complicated than in many states. A 2017 law requires approval from the Texas Historical Commission before any historically designated monument can be altered or removed.

This legal framework gives monument supporters powerful tools to prevent changes, even when local communities want them. The commission has rejected most removal requests, creating frustration among those who believe local governments should control their own public spaces.

Political divisions over Confederate symbols have hardened in recent years. What once might have been a local decision has become part of larger culture war debates.

State legislators have made monument preservation a partisan issue, with Republicans generally supporting protection laws and Democrats pushing for local control.

This politicization makes compromise harder because every decision becomes a statement about broader ideological positions rather than just local history.

Court cases continue to work through the system, challenging both removal attempts and preservation laws. Some argue that forced monument preservation violates First Amendment principles by compelling government speech.

Others contend that historical preservation laws serve legitimate purposes beyond politics. The legal landscape remains unsettled, and monuments like the one in Anderson exist in a kind of limbo, waiting for courts or legislatures to provide clearer guidance about how communities can navigate these difficult questions.

Address: 113 Loop 429, Anderson, TX 77830

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.