Webbers Falls sits along the Arkansas River in southeastern Oklahoma, a quiet town where Cherokee history runs deep and the landscape carries stories of resilience. Named for Walter Webber, a Cherokee chief who opened a trading post here in 1818, this riverside community has weathered more than two centuries of change.

Yet nothing altered its course quite like the flood of 2002, when the Arkansas River surged beyond its banks and reshaped life in ways the town is still reckoning with today.

Before that catastrophic May morning, Webbers Falls was a sleepy river town where neighbors knew each other by name and generations stayed rooted to the land. The river provided livelihood and identity, threading through daily routines and local lore.

But when the floodwaters arrived with sudden, overwhelming force, they didn’t just damage homes and roads. They rewrote the town’s narrative, scattering families, closing businesses, and forcing a reckoning with what it means to rebuild when the foundation itself has shifted.

Today, Webbers Falls remains small in population but large in spirit, a testament to the determination of those who chose to stay. Walking its streets, you’ll find traces of both loss and renewal, a community forever marked by water’s power and its own quiet refusal to disappear.

The Arkansas River and Its Historic Role

Long before highways crisscrossed Oklahoma, the Arkansas River served as the lifeblood of Webbers Falls, shaping trade routes and settlement patterns for centuries. Cherokee families navigated its currents, using the waterway to transport goods and connect distant communities.

Walter Webber recognized the river’s strategic importance when he established his trading post in 1818, positioning it near the seven-foot waterfall that would eventually bear his name.

The river brought prosperity and purpose to early settlers, offering fish, transportation, and fertile bottomland for crops. Generations grew up swimming in its eddies during summer, fishing from its banks at dawn, and listening to stories about the old days when steamboats occasionally made their way upstream.

The sound of moving water became the town’s constant backdrop, a reassuring presence that marked the rhythm of seasons and daily life.

Yet rivers are never fully predictable, and the Arkansas carried a dual nature that locals understood but rarely discussed openly. Spring rains could swell its flow, turning the gentle waterway into something more powerful and unpredictable.

Most years, the river stayed within its boundaries, respecting the unspoken agreement between water and land. But that balance was always temporary, always contingent on weather patterns and upstream conditions beyond anyone’s control.

By 2002, many residents had grown comfortable with the river’s presence, trusting levees and modern infrastructure to keep floodwaters at bay. That trust would be tested in ways no one imagined, revealing how quickly a familiar friend can become an overwhelming force when conditions align in catastrophic ways.

May 2002 and the Catastrophic Flood Event

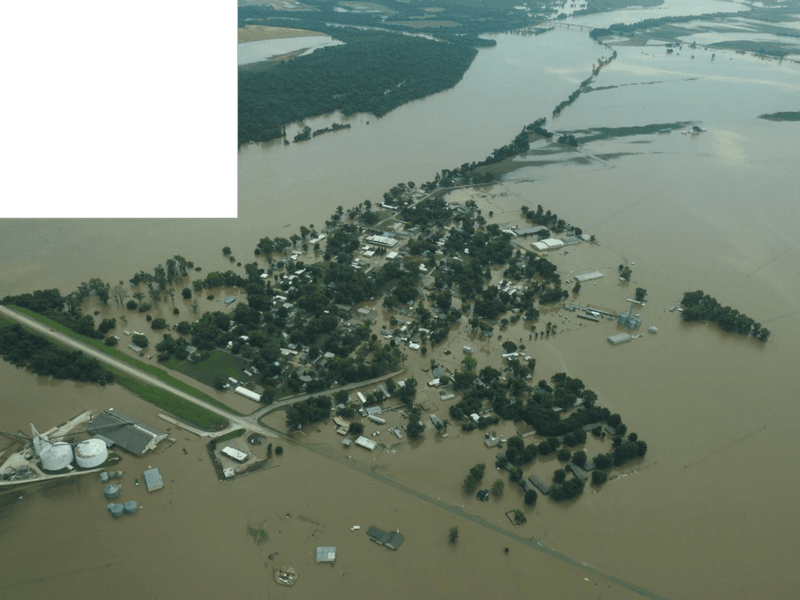

Dawn broke on May 26, 2002, with an urgency few in Webbers Falls had experienced before. Upstream dam releases combined with relentless rainfall created a surge that overwhelmed every protective measure the town relied upon.

Water poured over levees, through streets, and into homes with a speed that left little time for anything beyond grabbing essentials and running.

Families woke to water already climbing their doorsteps, rising inches every few minutes as the Arkansas River transformed from waterway to invading force. Some residents managed to drive to higher ground, while others were rescued by boat as floodwaters claimed entire neighborhoods.

The town’s low-lying areas disappeared beneath muddy currents, and structures that had stood for decades were suddenly submerged or swept away entirely.

Emergency responders worked around the clock, navigating treacherous conditions to reach stranded residents. Helicopters circled overhead, and rescue boats threaded through what had been residential streets just hours earlier.

The scope of the disaster became clear as daylight revealed a town transformed into a lake, with rooftops and treetops marking where homes and yards once stood.

When the waters finally receded days later, Webbers Falls faced devastation on a scale that defied easy description. Homes were ruined, businesses destroyed, and the infrastructure that supported daily life was compromised or gone.

The flood didn’t just damage property. It shattered the sense of security that comes from knowing your home and community will be there tomorrow, unchanged and familiar.

Population Decline and Community Dispersal

Numbers tell only part of the story, but they reveal the flood’s lasting impact with stark clarity. Before 2002, Webbers Falls maintained a stable population of families who had lived there for generations.

After the floodwaters receded, many faced an impossible choice between rebuilding in a flood zone or starting over somewhere safer and more certain.

Entire families packed what remained of their belongings and left, relocating to nearby towns like Muskogee or farther afield to cities with better job prospects and less traumatic memories. The 2010 census showed 616 residents, already a significant decline from pre-flood numbers.

By 2020, that figure had dropped to just 338 people, representing a loss of nearly half the population in a single decade.

Those who stayed often did so out of deep attachment to place, a refusal to let disaster erase their roots. But their town was fundamentally different now, quieter and emptier, with vacant lots where homes once stood and businesses that never reopened.

School enrollment dropped, forcing consolidations with neighboring districts. Churches that once hosted full Sunday services now struggled to maintain their congregations.

The social fabric that holds small towns together depends on critical mass, on enough people to staff volunteer fire departments, organize community events, and keep local businesses viable. Webbers Falls lost that critical mass in the flood’s aftermath, creating a cycle where population loss made the town less viable, which in turn encouraged more departures.

What remains is a community determined to survive but forever changed by the absence of those who left.

Economic Impact and Business Closures

Main Street in Webbers Falls once hummed with the modest but steady activity that defines small-town commerce. Local shops, a gas station, a diner where farmers gathered for morning coffee, these places provided not just goods and services but gathering points where community happened organically.

The flood swept away more than buildings when it tore through the business district.

Owners returned to find inventory ruined, equipment destroyed, and structures so compromised they couldn’t be salvaged. Insurance payouts, when they came, rarely covered the full cost of rebuilding, and many business owners lacked the resources or energy to start over from scratch.

Some were nearing retirement anyway and chose to close permanently rather than face years of debt and uncertainty.

The ripple effects extended far beyond individual storefronts. Each closed business meant fewer jobs, less tax revenue for the town, and fewer reasons for residents to stay local rather than driving to larger communities for their needs.

Young people who might have returned after college found no employment opportunities waiting. The economic engine that keeps small towns viable simply stopped running at full capacity.

Agriculture remained a constant, with farms surrounding Webbers Falls continuing to produce crops and livestock. But even farming operations faced challenges from flood-damaged equipment, contaminated fields, and the loss of local suppliers and service providers.

The economic landscape became one of survival rather than growth, with remaining businesses catering to a shrinking customer base and operating on thin margins that left little room for investment or expansion.

Infrastructure Damage and Reconstruction Challenges

Floodwaters don’t discriminate between private property and public infrastructure, and Webbers Falls discovered just how vulnerable its foundational systems were when the Arkansas River overtopped its banks.

Roads buckled and washed away, water and sewer lines were compromised, and the electrical grid suffered damage that took weeks to fully restore. The town’s modest budget, already stretched thin, faced repair costs that dwarfed available resources.

Federal and state emergency funds provided crucial assistance, but navigating the bureaucracy required expertise and persistence that small-town officials often lacked.

Applications for disaster relief involved complex documentation, strict deadlines, and requirements that sometimes seemed disconnected from the realities of a community in crisis.

Months passed between damage assessment and actual repairs, leaving residents to cope with compromised services and dangerous conditions.

Some infrastructure was rebuilt to higher standards, incorporating flood mitigation measures designed to prevent future catastrophes. Elevated roadbeds, improved drainage systems, and reinforced utilities represented progress but also constant reminders of vulnerability.

Other repairs were simply patched together with available funds, temporary solutions that everyone knew would need revisiting eventually.

The psychological toll of living with damaged infrastructure shouldn’t be underestimated. Boil water notices, road closures, and unreliable utilities created daily frustrations that compounded the trauma of the flood itself.

Residents who stayed had to accept a diminished quality of life, at least temporarily, and trust that improvements would eventually come. For a community already reeling from loss, these ongoing challenges tested patience and resilience in ways that weren’t always visible to outsiders.

Housing Crisis and Displacement

Home means something particular in small towns like Webbers Falls, where families often occupy the same houses for generations and property lines carry the weight of history. The flood turned homes into uninhabitable shells, filled with contaminated mud and water-damaged beyond simple repair.

What had been someone’s childhood bedroom or grandmother’s kitchen became a construction site or, worse, a teardown.

Displacement scattered families across the region, with some finding temporary shelter with relatives while others landed in motels or emergency housing that felt nothing like home.

Children changed schools mid-year, adults faced long commutes to jobs they’d once walked to, and the daily routines that provide stability dissolved overnight.

For elderly residents especially, the disruption proved devastating, severing connections to place that had sustained them for decades.

Federal trailer programs provided temporary housing for some families, but these solutions came with their own challenges. Trailers were cramped, poorly insulated, and often placed on lots where flood-damaged homes had stood, creating a constant reminder of loss.

Families that had owned homes outright suddenly found themselves in limbo, unable to afford rebuilding but reluctant to abandon property that represented their life’s investment.

The housing market in Webbers Falls effectively collapsed after the flood. Who would buy property in a proven flood zone?

Property values plummeted, trapping owners who wanted to leave but couldn’t sell. Those who did rebuild faced higher insurance costs and stricter building codes that added to expenses.

The housing crisis became both cause and effect of population decline, with each reinforcing the other in a cycle that the town struggled to break.

Environmental Changes to the Landscape

Floodwaters reshape more than human communities. They alter the land itself, depositing sediment, changing drainage patterns, and transforming ecosystems in ways that persist long after water levels return to normal.

Webbers Falls emerged from the 2002 flood with a landscape that looked familiar from a distance but revealed profound changes upon closer inspection.

Topsoil that had taken centuries to develop was stripped away in some areas, leaving behind less fertile subsoil that challenged farmers and gardeners. Other locations gained thick deposits of sediment, burying established vegetation and altering the grade of yards and fields.

Trees that had stood for decades died slowly from root damage, their decline visible over subsequent years as canopies thinned and limbs fell.

Wetland areas expanded as drainage patterns shifted, creating new habitat for waterfowl and amphibians but also increasing mosquito populations and making some formerly usable land too soggy for development. The riverbank itself was reconfigured, with erosion in some spots and new sandbars appearing in others.

These changes affected property lines, access points, and the visual character of a landscape that residents had known intimately.

Wildlife populations responded to the altered environment in complex ways. Some species thrived in newly created wetlands, while others struggled with the loss of established habitat.

Invasive plant species colonized disturbed areas quickly, outcompeting native vegetation and changing the appearance of roadsides and vacant lots.

The environmental legacy of the flood continues to unfold, a slow-motion transformation that will shape the region for generations to come, regardless of whether human communities fully recover.

Psychological Trauma and Community Resilience

Trauma settles into communities the way floodwater seeps into foundations, less visible than physical damage but just as pervasive and harder to remediate.

Residents of Webbers Falls who lived through the 2002 flood carry memories that surface unexpectedly during heavy rains, when weather forecasts mention flooding, or when they drive past empty lots where neighbors once lived.

The psychological cost of disaster doesn’t appear in damage assessments but shapes recovery as surely as insurance payouts and construction permits.

Anxiety and depression spiked in the flood’s aftermath, particularly among those who lost everything or were forced to relocate. Sleep disturbances became common as people replayed the chaos of evacuation or worried about future disasters.

Children exhibited behavioral changes, acting out fears they couldn’t articulate or withdrawing into themselves. Access to mental health services was limited in this rural area of Oklahoma, leaving many to cope without professional support.

Yet resilience emerged alongside trauma, expressed in the simple determination to keep going despite overwhelming loss. Neighbors helped neighbors clear debris, shared meals and temporary shelter, and offered the kind of practical support that small communities excel at providing.

These acts of mutual aid didn’t erase the pain but made it more bearable, creating bonds forged in shared adversity.

The community that remains in Webbers Falls today is smaller but perhaps more tightly knit, united by the knowledge of what they’ve survived together. Memorial events and flood anniversaries provide opportunities to acknowledge loss while celebrating persistence.

The psychological scars haven’t fully healed, may never fully heal, but they coexist with a quiet pride in having endured what many thought would finish the town entirely.

Webbers Falls Today and the Path Forward

More than two decades after floodwaters reshaped its destiny, Webbers Falls persists as a testament to the stubbornness of place and the people who refuse to let their town disappear. The population may have shrunk to 338 residents, but those who remain have chosen to stay with full knowledge of the risks and challenges.

Their presence represents a conscious decision that home matters more than safety or convenience.

The town looks different now, with empty spaces where structures once stood and a quietness that speaks to absence. Yet signs of life persist in maintained yards, open churches, and the few businesses that continue serving the community.

Local government functions with limited resources but genuine commitment, focusing on essential services and gradual improvements rather than ambitious growth plans that feel disconnected from reality.

Flood mitigation remains a priority, with improved levees, better emergency planning, and enhanced communication systems designed to provide earlier warnings if the Arkansas River threatens again.

These measures offer some reassurance but can’t eliminate the fundamental vulnerability that comes from living in a floodplain.

Residents have made peace with this reality, accepting risk as the price of staying rooted to land that holds their history.

Looking forward, Webbers Falls faces an uncertain future shaped by demographics, economics, and environmental factors beyond local control. The town may continue its gradual decline, eventually joining the ranks of ghost towns that dot rural Oklahoma.

Or it may stabilize at its current size, a small but viable community that preserves its identity against considerable odds. Either way, the 2002 flood will remain the defining event in modern memory, the moment when everything changed and the path forward became something no one had anticipated or chosen.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.