Paris, Texas greets you with exactly what you would expect at first glance: boots in shop windows, sweet tea on tables, and a cowboy-hatted Eiffel Tower rising above town. Paris embraces its charm openly.

Stay a little longer and the mood becomes more layered. Conversations remain easy until certain topics surface.

Then voices lower, pauses stretch, and words are chosen more carefully. On the edge of town, the Lamar County Fairgrounds appears ordinary to most visitors.

The grounds have hosted community gatherings for generations, yet they are also connected to a history that carried weight for decades. Understanding this town means acknowledging both its inviting spirit and the difficult chapters that still linger beneath the surface.

A Tower With a Cowboy Hat That Says It All

Standing in the middle of a small Texas town is a 65-foot Eiffel Tower topped with a bright red cowboy hat. I couldn’t help but smile when I first saw it.

It’s exactly the kind of quirky landmark that makes small-town America so lovable. Built in 1993, this miniature monument is Paris, Texas, in a nutshell: proud, a little cheeky, and fully aware of the joke.

But the tower also represents something else. It’s the face the town wants you to see.

The postcard image. The thing that gets shared on social media and draws road trippers off the highway.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. Every town needs an identity, a hook that makes people stop and take a picture.

What struck me, though, was how much energy goes into promoting this symbol while other parts of the town’s story stay buried. The Eiffel Tower is fun and harmless, a conversation starter that never gets uncomfortable.

It’s easier to talk about a hat on a tower than what happened a few blocks away over a century ago. Still, I took my photo.

Everyone does.

It’s part of the ritual of visiting Paris, Texas.

The Fairgrounds Nobody Mentions

The Lamar County Fairgrounds look ordinary enough. I drove past them twice before realizing what they were.

There’s no plaque, no marker, nothing that signals the horror that unfolded here more than a century ago. But this ground is soaked in one of the darkest chapters of American history.

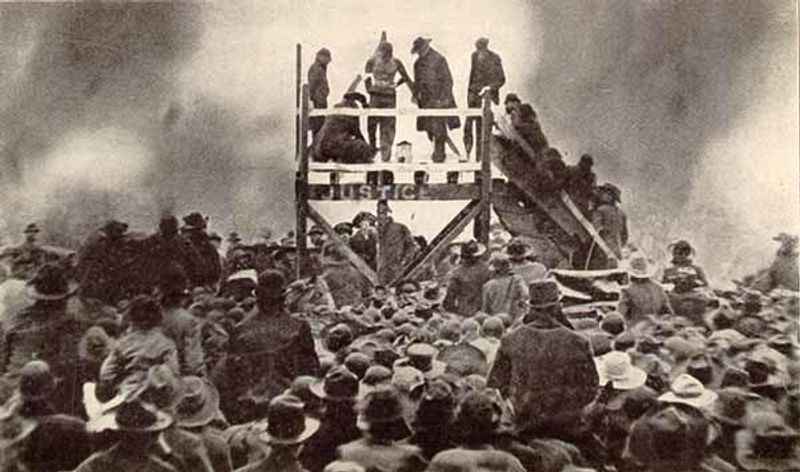

In 1893, a Black man named Henry Smith was tortured and burned alive here in front of an estimated 10,000 spectators. The event was advertised.

Trains brought people in from neighboring towns. Photographers sold postcards of the scene afterward.

It wasn’t a secret. It was a spectacle.

Then, in 1920, two Black teenagers, the Arthur brothers, were also lynched here in another public display of racial terror. Again, thousands attended.

Again, it was documented. And yet, for decades, Paris stayed silent about it.

No memorials. No acknowledgment.

Just a collective decision not to talk about what happened on this land. Walking near the fairgrounds today, you’d never know.

But locals do.

And for many, it remains a subject too painful or too controversial to bring up in polite conversation.

Postcards of Lynching Sold as Souvenirs

One of the most chilling aspects of these lynchings is how they were commodified. Photographers at the scene took pictures and turned them into postcards that were sold and mailed across the country.

I came across references to these images in historical archives, and they’re almost impossible to process. People sent them like vacation snapshots.

The postcards weren’t hidden or underground. They were sold openly, sometimes with captions that celebrated the violence.

This wasn’t just mob rule. It was a culture that normalized and even celebrated racial terror.

The fact that these images circulated so freely shows how deeply embedded this violence was in the social fabric of the time.

Today, some of those postcards are preserved in museums and academic collections as evidence of this brutal history. But in Paris, Texas, they’re rarely discussed.

There’s discomfort around confronting how public and proud these acts were. It’s one thing to acknowledge a dark past.

It’s another to reckon with the fact that it was celebrated, documented, and shared.

That level of honesty is still hard for many to face.

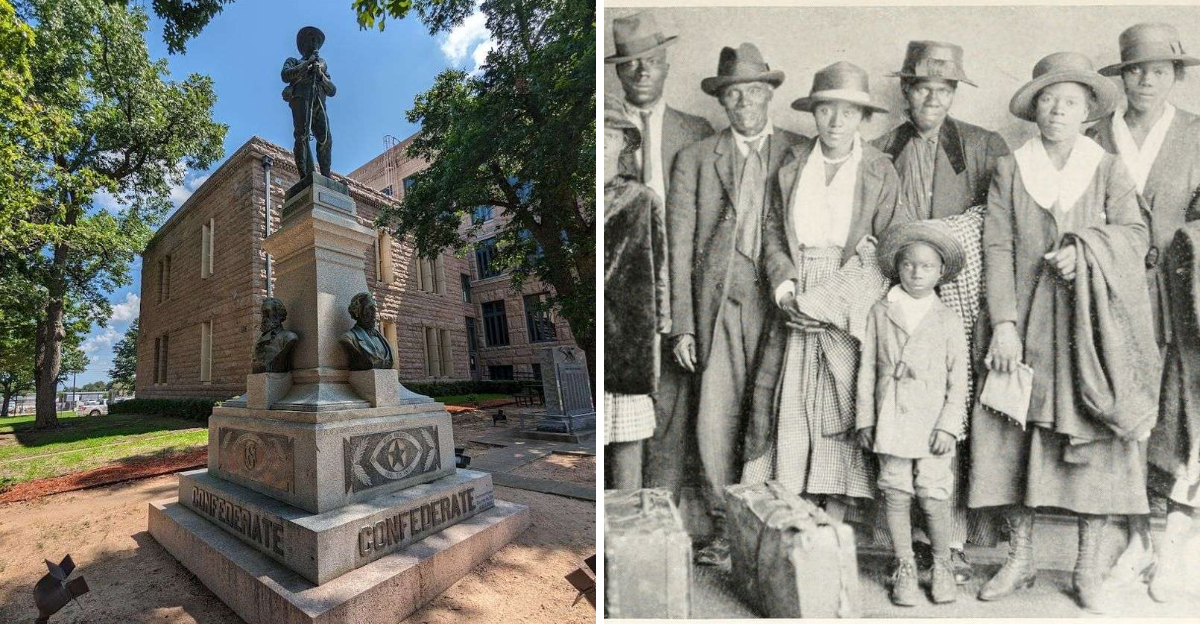

A Confederate Monument Still Stands

Right in the heart of downtown Paris, on the Lamar County Courthouse lawn, stands a Confederate monument. It’s tall, prominent, and impossible to miss.

For some, it’s a tribute to history and heritage. For others, it’s a painful reminder of whose history gets honored and whose gets erased.

I stood there for a while, watching people walk by without a second glance. The monument has been there for decades, part of the landscape.

But its presence is anything but neutral, especially in a town where the history of racial violence is so raw and unresolved. The juxtaposition is stark.

A monument to the Confederacy stands proud, while the victims of lynching went unmarked for over a century.

Efforts to remove or relocate Confederate monuments have sparked intense debate across the South, and Paris is no exception. For many residents, touching the monument feels like erasing history.

For others, leaving it up feels like endorsing it. There’s no easy middle ground.

What’s clear is that the monument represents more than stone and metal. It’s a symbol of which stories a community chooses to preserve and which it struggles to confront.

Address: 119 N Main St, Paris, TX 75460

The 2020 Remembrance Ceremony That Broke the Silence

For nearly a century, there was no public acknowledgment of the Arthur brothers’ lynching. Then, in 2020, something shifted.

A remembrance ceremony was held at the Red River Valley Veterans Memorial, and for the first time, the city of Paris formally apologized. I read accounts of the event, and the emotion was palpable.

Descendants of the victims attended. Community leaders spoke.

It was a long overdue reckoning.

But it didn’t come easily. The ceremony was the result of years of pressure from activists, historians, and families who refused to let the story stay buried.

Even then, not everyone in town supported it. Some felt it was unnecessary, that dredging up the past only caused division.

Others believed it was essential for healing.

What struck me most was how rare this kind of public accountability still is. Across the South, there are countless sites of racial violence that remain unmarked and unacknowledged.

Paris took a step that many towns still refuse to take. It wasn’t perfect, and it didn’t erase the pain, but it was a start.

The question now is whether that momentum continues or fades back into the silence that defined the town for so long.

A Tourism Image Built on Charm, Not Truth

Paris, Texas, markets itself as a charming small town with big heart. The tourism websites highlight the Eiffel Tower, the historic downtown, the annual events.

There are murals, antique shops, and friendly faces. And honestly, it is charming.

I enjoyed walking through the downtown square, stopping in local shops, and chatting with people who clearly love their community.

But there’s an elephant in the room, and it’s the size of the fairgrounds. The town’s brand is built on nostalgia and Southern hospitality, but that image doesn’t leave room for the harder truths.

Tourists aren’t coming to Paris to learn about lynching. They’re coming for the photo op with the Eiffel Tower and maybe some barbecue.

And the town knows that.

There’s a tension between preserving the town’s economic identity and confronting its past. Tourism dollars matter, especially in a small town.

But so does integrity. Some residents are pushing for more education, more markers, more honesty in how Paris presents itself.

Others worry that focusing on the negative will drive visitors away.

It’s a delicate balance, and one that Paris is still very much navigating.

Red River Valley Veterans Memorial: Where Apology Finally Happened

The Red River Valley Veterans Memorial is a quiet, reflective space on the edge of town. It’s dedicated to honoring military service, but in 2020, it became the site of something equally significant: a public apology and remembrance for the Arthur brothers.

I visited the memorial, and it felt like hallowed ground, though not in the way it was originally intended.

Choosing this location for the ceremony was symbolic. It’s a place associated with sacrifice and honor, and holding the remembrance here was a way of saying that the Arthur brothers deserved that same respect.

Their deaths were not just tragedies. They were injustices that the community had a responsibility to acknowledge.

The memorial itself doesn’t yet have a permanent marker for the lynching victims, though there have been discussions about adding one. For now, it remains a veterans’ space first, with the memory of the 2020 ceremony lingering in the background.

But the fact that it happened here at all is significant. It shows that Paris is capable of change, even if that change is slow and uncomfortable.

Address: 2035 S Collegiate Dr, Paris, TX 75460

The Ongoing Struggle Between Memory and Silence

Walking through Paris, Texas, I kept thinking about what it means to live in a place with this kind of history. For some residents, especially Black families, the past isn’t past.

It’s present in every conversation about race, every debate about monuments, every moment of silence when the fairgrounds come up. For others, it’s ancient history, something that happened long before they were born and doesn’t define who they are today.

But history doesn’t disappear just because we stop talking about it. It lingers in the landscape, in the gaps of what gets taught in schools, in the discomfort that rises when someone asks too many questions.

Paris is still figuring out how to hold both its pride and its shame, how to be a town that loves itself while also being honest about what happened here.

There’s no easy resolution. Some towns choose to bury their past.

Others confront it head-on. Paris is somewhere in between, inching toward acknowledgment but still wrestling with what that looks like.

What I took away is that this struggle isn’t unique to Paris. It’s happening in small towns and big cities across America.

The difference is whether people are willing to talk about it.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.