I still remember my first visit to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, back when bison grazed peacefully and elk moved through the landscape without a care.

Located at 32 Refuge Headquarters Road in Indiahoma, Oklahoma, this 59,020-acre sanctuary was established in 1901 to protect disappearing species and preserve wild spaces.

Fast forward to recent years, and I’ve watched something troubling unfold. Visitors now crowd around animals with phones extended, attempting selfies with buffalo and hand-feeding prairie dogs like they’re at a county fair.

The refuge that once embodied true wilderness has become a backdrop for social media posts, with tourists treating magnificent creatures as props rather than wild animals deserving respect and distance.

Every state has its wildlife challenges, but what’s happening in Oklahoma highlights a nationwide problem: we’ve forgotten how to be guests in nature’s home.

Bison Encounters Have Become Dangerously Close

Walking the refuge roads now feels like navigating a wildlife paparazzi convention. I’ve seen families park their cars within feet of grazing bison, children tumbling out with snacks extended toward animals that weigh up to 2,000 pounds.

These magnificent creatures aren’t pets, despite what Instagram might suggest. Bison can run 35 miles per hour and turn aggressive when threatened or approached.

Yet I’ve witnessed tourists circling herds, trying to touch calves, and positioning toddlers mere yards away for that perfect photo opportunity. The refuge staff posts warnings everywhere, but they’re largely ignored.

During one visit last spring, I watched a buffalo charge at a man who’d crept too close, sending him scrambling back to his vehicle. He was lucky.

Others haven’t been, resulting in injuries that could have been avoided with basic respect for wild animals. Park rangers now spend more time managing crowds than protecting wildlife.

The bison that once roamed freely across the landscape have learned to associate humans with food and attention, fundamentally altering their natural behavior in ways seen across parks nationwide.

Prairie Dog Towns Have Turned Into Feeding Frenzies

The prairie dog viewing area used to be my favorite stop. These social creatures would pop up from their burrows, chirping warnings to each other while going about their daily routines.

Now it resembles a petting zoo snack bar. Visitors arrive armed with bread, crackers, and chips, tossing food into the colony despite massive signs prohibiting feeding.

I’ve watched prairie dogs become so habituated to human food that they now approach cars expectantly, standing on hind legs like trained circus performers. This artificial feeding creates serious health problems for the animals.

Prairie dogs need specific diets of grasses and seeds, not processed human snacks. The unnatural food sources lead to nutritional deficiencies, obesity, and dental issues that wouldn’t exist in their natural state.

Beyond health concerns, the constant human interaction has disrupted their social structures. Young prairie dogs learn to beg rather than forage, losing survival skills that would serve them in truly wild conditions.

Rangers have tried blocking access during peak times, but the damage continues whenever gates open. Similar feeding problems occur across wildlife areas, showing this isn’t just an Oklahoma issue but a reflection of how we’ve lost understanding of proper wildlife interaction.

Elk Have Lost Their Natural Wariness of Humans

Bull elk with massive antlers once kept respectful distances from hiking trails. During my recent visits, I’ve watched these powerful animals graze within arm’s reach of gawking tourists who seem oblivious to the danger.

Elk are particularly unpredictable during rutting season, yet I’ve seen people approach bulls in full mating display, antlers lowered and testosterone running high. The animals’ natural flight response has been replaced with tolerance born from constant human presence and, unfortunately, intentional feeding by irresponsible visitors.

One afternoon near the visitor center, I observed a cow elk with her calf surrounded by a dozen people snapping photos. The mother showed signs of stress, ears back and nostrils flaring, but the crowd pressed closer.

This scenario repeats daily across the refuge, teaching elk that humans pose no threat. The problem extends beyond immediate safety concerns.

Elk that lose their wildness become dependent on human-populated areas, increasing vehicle collisions and creating management nightmares for refuge staff.

What worked in other national forests for maintaining wildlife boundaries has been ignored here, and we’re watching real-time consequences of treating observation areas like petting zoos rather than wildlife sanctuaries.

Longhorn Cattle Are Treated Like Farmyard Attractions

The refuge’s longhorn cattle serve as living history, representing the ranching heritage of the American Southwest. Tourists now treat them like tame farm animals ready for a barnyard visit.

I’ve watched people lean over fences trying to pet longhorns, apparently forgetting that those impressive horns can span six feet or more. These aren’t docile dairy cows.

They’re semi-wild cattle with strong territorial instincts and the physical capability to cause serious harm when provoked. During one visit, a family attempted to feed longhorns through a fence line, waving sandwiches and calling to them like house pets.

The cattle approached, and suddenly the children panicked when they realized how massive and intimidating these animals actually are up close. The parents laughed it off, but they’d just taught their kids that wild animals exist for human entertainment.

Rangers have increased patrols near longhorn areas, but enforcement remains challenging when hundreds of visitors arrive daily with the same misguided intentions. The cattle have begun congregating near roads and parking areas, expecting handouts rather than grazing naturally across the landscape.

This behavioral shift mirrors problems in agricultural areas where wildlife-human boundaries have blurred, creating situations that benefit neither species.

Hiking Trails Have Become Selfie Stations

Trails that once offered solitary communion with nature now resemble outdoor photo studios. I’ve hiked the Narrows Trail and Elk Mountain paths dozens of times, and the transformation is startling.

Groups cluster at scenic overlooks, not to appreciate the view but to stage elaborate photo shoots. I’ve waited twenty minutes at a single viewpoint while visitors cycled through poses, outfit changes, and increasingly elaborate prop arrangements.

The actual hiking becomes secondary to content creation. This wouldn’t be problematic if it stayed on designated trails, but the quest for unique backgrounds has led to extensive off-trail trampling.

Fragile prairie vegetation gets crushed as people seek less-photographed angles. Rock formations show damage from climbers seeking that perfect elevated shot, ignoring signs marking sensitive geological features.

The noise level has increased dramatically too. Trails that once offered birdsong and wind through grass now echo with loud conversations, music from portable speakers, and constant photo direction.

Wildlife that used to be visible from hiking paths has retreated to more remote areas, making genuine nature observation increasingly difficult.

Other state parks face similar issues, but the concentration of inappropriate behavior at Wichita Mountains has reached particularly concerning levels, fundamentally changing what should be a wilderness experience.

Mount Scott Summit Has Lost Its Peaceful Character

Driving up Mount Scott used to be a meditative experience culminating in breathtaking views across southwest Oklahoma. The summit now feels like a carnival parking lot on busy weekends.

Cars pack the summit area, engines running while occupants sit inside scrolling through phones, apparently having driven up simply to say they did it. The observation points are constantly crowded with people more focused on their screens than the actual 360-degree views stretching to the horizon.

I’ve watched visitors arrive, snap a quick photo, and leave within five minutes, never actually experiencing the place.

The sunset viewing that once drew respectful nature lovers now attracts loud parties treating the mountain like a outdoor venue for social gatherings rather than a place for quiet reflection.

Litter has become a persistent problem despite multiple trash receptacles. I’ve picked up discarded water bottles, food wrappers, and even abandoned camping chairs from the summit area.

Rangers close vehicle access until noon to manage crowds, but this only concentrates the chaos into afternoon and evening hours. The wildlife that once frequented the summit area has largely disappeared, driven away by constant human presence.

This mirrors overcrowding issues in mountain parks, where popular viewpoints lose their essential character when treated as mere photo backdrops rather than natural spaces deserving reverence and care.

The Visitor Center Has Become an Afterthought

The refuge visitor center offers incredible educational resources, historical context, and crucial safety information. Most tourists now skip it entirely, heading straight to animal viewing areas without any preparation or understanding.

I always stop at the visitor center first, where knowledgeable staff provide trail recommendations, weather updates, and current wildlife locations. They explain proper viewing distances, why feeding is prohibited, and how to stay safe around large animals.

This information proves invaluable, yet parking lots near bison areas overflow while the visitor center sits nearly empty. The center’s museum displays tell the refuge’s conservation story, explaining how bison were saved from extinction and why protecting wild spaces matters.

These exhibits provide context that transforms a casual visit into meaningful understanding, but they’re ignored by people seeking only quick animal encounters and photo opportunities. Staff members express frustration at repeatedly addressing problems that proper visitor center orientation would prevent.

They’ve developed excellent educational materials, but can’t force people to engage with them. The disconnect between available resources and visitor behavior reveals how we’ve reduced wildlife refuges to entertainment venues rather than conservation areas requiring informed participation.

Similar patterns appear in other nature centers, where education facilities go underutilized while problems from uninformed visitors multiply. The visitor center represents everything a wildlife refuge should be, yet it’s become increasingly irrelevant to the average tourist’s experience.

Rock Climbing Areas Show Environmental Damage

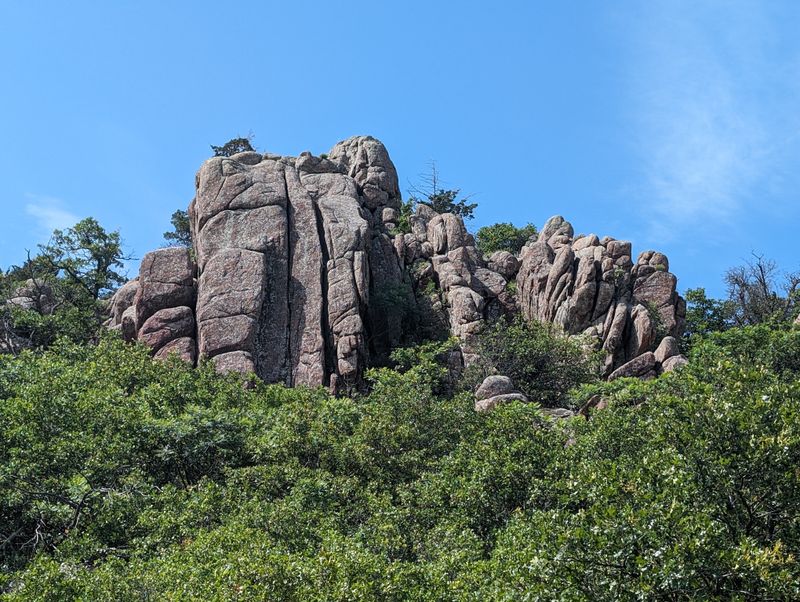

Wichita Mountains offers some of Oklahoma’s best rock climbing on ancient granite formations. The climbing areas now show visible damage from overuse and improper technique by inexperienced visitors treating boulders like jungle gyms.

Established climbing routes have expanded as people create new paths without regard for vegetation or rock integrity. I’ve watched families with young children scramble over fragile rock faces, dislodging stones and damaging lichen that took decades to establish.

The distinctive red granite that makes these formations special shows chalk marks, scratches, and other signs of disrespectful use. Proper climbing ethics require leaving no trace, but trash accumulates around popular boulder problems.

Abandoned gear, food waste, and even graffiti mar areas that should remain pristine. Rangers lack resources to monitor every climbing area, relying on visitor cooperation that increasingly doesn’t materialize.

The climbing community itself has tried to promote responsible practices, but they’re overwhelmed by casual visitors who see rocks as playground equipment rather than natural features requiring care.

Erosion around high-traffic boulders has accelerated, threatening the long-term stability of formations that have stood for millions of years.

Climbing areas face similar challenges, but the concentration of inexperienced users at Wichita Mountains has created particularly acute problems. What should be a sustainable recreation activity has become another example of loving a place to death through thoughtless overuse.

Lake Areas Have Become Picnic Party Zones

The refuge’s lakes and reservoirs provide crucial habitat for waterfowl, fish, and amphibians while offering scenic beauty. Shoreline areas now resemble city park picnic grounds on summer weekends, with wildlife taking a distant back seat to recreation.

I’ve watched lake access points transform into crowded gathering spaces where noise and activity drive away the very wildlife people supposedly came to see. Fishing remains popular, but proper catch-and-release practices often get ignored in favor of keeping every catch regardless of size or season.

Shorelines show erosion from foot traffic extending far beyond designated access points. Littering around lakes has become particularly problematic.

Fishing line tangles in vegetation where it poses deadly threats to birds and turtles. Food waste attracts raccoons and other opportunistic species, artificially concentrating them in areas where they wouldn’t naturally gather in such numbers.

The peaceful contemplation that lake environments offer has been replaced by constant activity. Portable speakers blast music across water that should carry only bird calls and wind.

People wade into restricted areas, disturbing nesting sites and trampling aquatic vegetation that provides essential habitat. Water quality concerns have emerged as increased human use introduces pollutants and disrupts natural systems.

Many visitors to the Wichita Mountains treat the refuge’s waters like a personal playground, forgetting that protecting wildlife comes first and that every splash can have real ecological consequences.

Wildlife Photography Has Crossed Ethical Lines

Wildlife photography can be a powerful conservation tool when done ethically. At Wichita Mountains, the pursuit of dramatic images has led to increasingly problematic behavior that prioritizes photos over animal welfare.

I’ve encountered photographers using bait to lure animals closer, making noise to provoke reactions, and deliberately separating young from mothers to capture “cute” isolation shots.

These tactics create stress for animals and teach them to associate humans with food or threats, fundamentally altering natural behaviors.

The rise of social media has intensified these problems. Photographers compete for unique images that will generate engagement, leading to riskier approaches and more invasive techniques.

I’ve seen people crawl toward nesting birds, corner prairie dogs against burrows, and use vehicles to herd bison into better lighting, all for that perfect shot.

Professional photographers following ethical guidelines get lumped together with amateurs who don’t understand or care about proper wildlife photography ethics.

The distinction matters because responsible photography requires patience, long lenses, and willingness to accept that some shots simply aren’t worth pursuing if they disturb animals. Refuge staff have implemented photography guidelines, but enforcement remains challenging.

The damage extends beyond individual animal encounters to broader habituation patterns that undermine the refuge’s conservation mission.

Other wildlife areas have developed stricter photography regulations in response to similar problems, but Wichita Mountains continues struggling to balance access with protection, watching as the line between documentation and exploitation grows increasingly blurred.

The Path Forward Requires Visitor Responsibility

Reversing the damage requires fundamental shifts in how visitors approach the refuge. This isn’t about closing access but about rekindling respect for wild places and the creatures that inhabit them.

I’ve seen positive examples: families using binoculars instead of approaching animals, hikers staying on designated trails, and photographers waiting patiently at respectful distances. These visitors understand that wildlife refuges exist primarily for animals, with human access being a privilege requiring responsible behavior.

When everyone adopts this mindset, the refuge can recover its wild character. Education remains crucial.

The visitor center needs to become a mandatory first stop, where people learn proper etiquette before entering animal areas. Enhanced ranger presence, while resource-intensive, provides both enforcement and education opportunities.

Clear consequences for feeding animals, approaching too closely, or leaving trails would establish that violations won’t be tolerated. Technology could help too.

Apps providing real-time wildlife locations at safe viewing distances would reduce dangerous encounters while improving viewing opportunities. Social media campaigns highlighting responsible behavior might shift the culture from conquest to conservation.

Refuge management has implemented similar strategies with measurable success. Ultimately, saving the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge from petting zoo treatment depends on individual choices.

Every visitor who maintains proper distance, stays on trails, and prioritizes animal welfare over photo opportunities contributes to restoration. The wild Oklahoma landscape that inspired the refuge’s creation still exists, but only if we remember we’re guests in someone else’s home.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.