Wyoming holds secrets that most travelers never discover during their visits to the state’s famous national parks.

Beyond Yellowstone and Grand Teton lie extraordinary natural formations that locals have treasured for generations, places where geology performs impossible tricks and ancient mysteries remain unsolved.

From singing sand dunes to rivers that vanish into the earth, these hidden wonders reveal a side of Wyoming that guidebooks rarely mention.

Each destination offers something genuinely unusual, whether it’s water flowing to two different oceans or rocks that defy the laws of time itself.

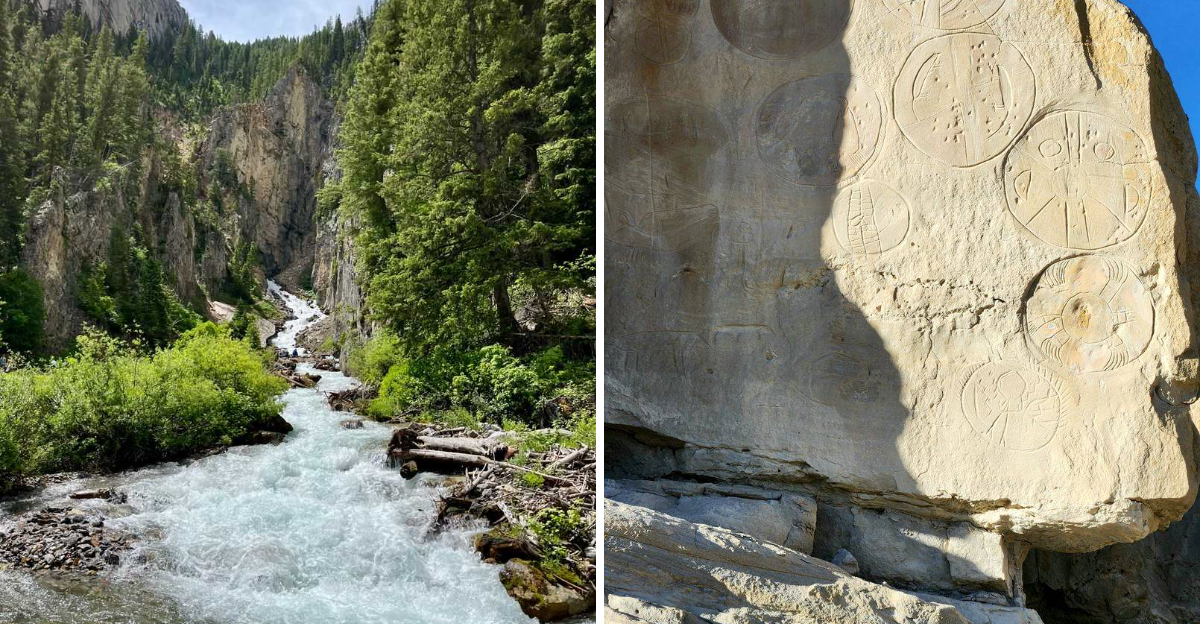

1. Intermittent Spring Near Afton

Water gushes from a rocky cliff face with the regularity of a heartbeat, creating one of nature’s most puzzling displays.

Every 12 to 18 minutes, this spring releases thousands of gallons before stopping completely, then starting again with perfect rhythm.

Scientists have studied this phenomenon for decades, yet the exact mechanism remains partially mysterious.

The spring holds the title of largest rhythmic spring on Earth, making it a geological celebrity among those who know where to find it.

Locals from Afton have grown up with this natural wonder, treating it as their own backyard attraction.

The hike to reach the spring takes about 45 minutes through beautiful forest terrain, passing through wildflower meadows in summer.

Most theories suggest an underground siphon system causes the intermittent flow, similar to a natural toilet flush mechanism.

When the hidden underground chamber fills to a certain level, pressure forces water through the outlet until the chamber empties.

Visitors who time their arrival correctly can witness the dramatic moment when silence breaks into rushing water.

The spring flows most reliably during late spring and early summer when snowmelt feeds the underground system.

By late summer, the flow may become less predictable or stop entirely until the following year.

Photography enthusiasts appreciate the challenge of capturing both the flowing and dormant states.

The surrounding Swift Creek Canyon provides additional scenic beauty with limestone cliffs and dense vegetation.

Few tourists venture here despite its proximity to major highways, keeping it pleasantly uncrowded throughout most seasons.

2. Killpecker Sand Dunes

Golden waves of sand stretch across 109,000 acres north of Rock Springs, creating an unexpected Sahara in the middle of Wyoming.

These dunes rank among the largest active sand fields in North America, constantly shifting and reforming with prairie winds.

Something truly extraordinary happens here that occurs in only six other places worldwide.

The dunes produce audible sounds, earning them the designation as one of Earth’s rare booming or singing sand formations.

When conditions align perfectly with dry sand and steady wind, the dunes emit low-frequency rumbles or high-pitched whistles.

Scientists believe the sound results from friction between specially shaped sand grains as they cascade down steep slopes.

Local ranchers and adventurers have known about these musical sands for generations, though the phenomenon still surprises first-time visitors.

The landscape feels utterly alien compared to typical Wyoming scenery, with minimal vegetation and endless sandy horizons.

Wild horses roam freely through this desert environment, their hoofprints creating temporary patterns that disappear with the next windstorm.

Sandboarding and sand sledding have become popular activities for those who discover this remote location.

The dunes offer spectacular photography opportunities, especially during golden hour when shadows accentuate every ripple and curve.

Summer temperatures can become extremely hot, making spring and fall the most comfortable seasons for exploration.

No facilities exist within the dune field itself, so visitors must come prepared with adequate water and sun protection.

The isolation and vastness create a sense of solitude rarely found in more developed tourist destinations.

3. Boar’s Tusk Volcanic Plug

A jagged spire of dark volcanic rock pierces the horizon like a giant’s fang, visible from miles across the flat desert landscape.

This 400-foot tower represents the hardened core of an ancient volcano that erupted millions of years ago.

Everything else eroded away over countless centuries, leaving only this resistant plug of volcanic material standing alone.

The formation gets its name from the resemblance to a wild boar’s curved tusk jutting from the earth.

Geologists estimate the volcano was active during the Oligocene epoch, roughly 25 to 30 million years before humans walked the planet.

Rock climbers occasionally attempt to scale the crumbling volcanic rock, though the ascent presents significant challenges and dangers.

The surrounding landscape consists of sagebrush desert and badlands, making the vertical plug even more visually striking.

Photographers love capturing the formation during sunrise and sunset when dramatic lighting emphasizes its sculptural qualities.

Local residents use Boar’s Tusk as a landmark for navigation across the otherwise featureless terrain.

The site sits on public land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, accessible via dirt roads that can become impassable after rain.

Wildlife including pronghorn antelope, coyotes, and various raptors inhabit the area around the formation.

The isolation means visitors often have the entire landmark to themselves, creating opportunities for contemplation and solitude.

Fossil hunters sometimes explore the surrounding badlands, where ancient mammal remains occasionally surface from eroding hillsides.

The stark beauty appeals to those who appreciate desert landscapes and geological curiosities off the beaten path.

4. Sinks Canyon State Park

A river performs a vanishing act that has puzzled observers for centuries, flowing into a cave and disappearing completely from view.

The Popo Agie River rushes along normally until reaching a limestone cavern where it plunges underground and vanishes.

Quarter of a mile downstream, the water mysteriously reappears at a spot called The Rise, bubbling up into a large pool.

Scientists conducted dye tests expecting the water to take minutes to travel underground between the two points.

Instead, the dye took over two hours to appear, indicating a complex underground route through hidden chambers and passages.

Even stranger, more water emerges at The Rise than enters at The Sinks, suggesting additional underground sources feed the system.

Large rainbow and brown trout thrive in the cold, clear pool at The Rise, visible to visitors who peer into the depths.

The fish cannot be caught due to park regulations protecting this unique environment.

Limestone formations throughout the canyon reveal millions of years of geological history through visible rock layers.

Hiking trails wind through the canyon, offering access to both The Sinks and The Rise with interpretive signs explaining the phenomenon.

Rock climbers frequent the canyon walls, which provide challenging routes on solid limestone.

Wildlife including bighorn sheep, moose, and black bears inhabit the surrounding mountains and forests.

The park sits just outside Lander, making it more accessible than many Wyoming natural wonders yet still relatively unknown to out-of-state visitors.

Locals treat the canyon as a favorite spot for picnics, nature walks, and introducing children to geological mysteries.

5. Heart Mountain

An 8,123-foot peak presents geologists with a puzzle that challenged scientific understanding for decades.

The summit consists of rocks that are 300 million years older than the rocks at the base, a complete reversal of normal geological order.

Typically, younger rocks sit atop older layers, but Heart Mountain flipped this rule upside down.

The explanation involves one of the most catastrophic geological events ever documented on Earth.

Approximately 50 million years ago, a massive section of ancient seafloor broke loose and slid over 60 miles across the landscape.

This Heart Mountain Detachment moved at speeds that still amaze scientists, possibly traveling on a cushion of pressurized fluids or gases.

The resulting formation left older limestone sitting impossibly atop much younger rock layers.

Beyond its geological significance, Heart Mountain carries profound historical weight from more recent times.

During World War II, the U.S. government established an internment camp at the mountain’s base, imprisoning nearly 14,000 Japanese Americans.

The Heart Mountain Interpretive Center now preserves this difficult chapter of American history, educating visitors about the camp’s existence.

Hiking trails lead to various viewpoints where both the geological anomaly and historical site can be contemplated.

The mountain’s distinctive heart-shaped profile becomes visible from certain angles, explaining its romantic name.

Local ranchers graze cattle on the lower slopes, continuing land use patterns that predate the internment camp.

The combination of extraordinary geology and significant history makes this location uniquely important on multiple levels.

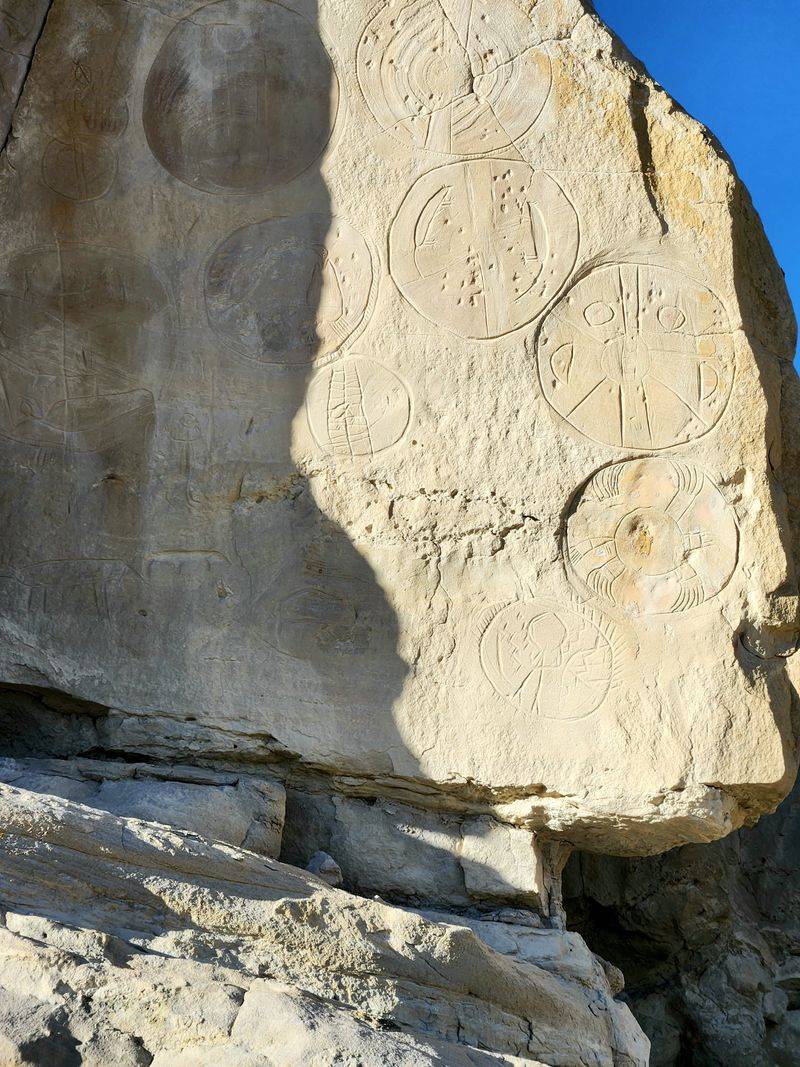

6. Castle Gardens Petroglyph Site

Sandstone towers rise from the badlands like the ruins of an ancient fortress, their walls decorated with mysterious symbols.

Wind and water sculpted these formations over thousands of years, creating castle-like structures with natural alcoves and overhangs.

Native peoples recognized the site’s special qualities long ago, using the sheltered rock faces as canvases for their artwork.

Hundreds of petroglyphs cover the sandstone walls, pecked into the rock surface using stone tools.

The images include human figures, animals, geometric patterns, and symbols whose meanings remain subjects of scholarly debate.

Unlike pictographs which use pigments, these petroglyphs were created by removing the dark desert varnish to reveal lighter rock beneath.

Some carvings date back thousands of years, representing multiple cultural periods and different Native American groups.

The site’s remote location helped protect it from vandalism that has damaged more accessible rock art sites.

Visitors must travel 25 miles on dirt roads from the nearest paved highway, discouraging casual tourists.

The Bureau of Land Management maintains minimal facilities, preserving the site’s wild character.

Interpretive signs provide context about the petroglyphs and the peoples who created them, though many mysteries remain unsolved.

The surrounding badlands offer additional exploration opportunities with colorful eroded hills and fossil-bearing layers.

Photographers find endless compositions combining the sculptural rock formations with ancient human artwork.

Locals from Riverton and surrounding communities visit Castle Gardens as a connection to the region’s deep human history.

7. Parting of the Waters

A small creek reaches a fork and makes an impossible decision, sending water toward two different oceans simultaneously.

North Two Ocean Creek splits at this remote location in the Teton Wilderness, creating one of Earth’s rarest hydrological features.

One branch flows west, eventually joining the Snake River, then the Columbia, finally reaching the Pacific Ocean.

The other branch travels east, merging with the Yellowstone River, then the Missouri, the Mississippi, and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean.

This occurs because the split happens precisely on the Continental Divide, where water can legitimately flow in either direction.

Only a handful of such locations exist worldwide where a natural stream divides to reach separate oceans.

The exact split point shifts slightly from year to year as erosion and debris alter the streambed configuration.

During high water in spring, the division becomes more dramatic with substantial flows heading both directions.

By late summer, the creek may shrink to a trickle, making the split less impressive but no less significant.

Reaching this spot requires serious commitment, involving either a long backpacking trip or horseback journey into wilderness.

No roads approach the site, preserving its pristine condition and limiting visitors to those willing to make the effort.

The surrounding wilderness provides habitat for grizzly bears, wolves, elk, and other wildlife requiring undisturbed landscapes.

Outfitters in the region offer guided pack trips that include Parting of the Waters as a highlight destination.

The simple act of standing at this geographic oddity creates a profound connection to continental-scale geography and water systems.

8. Bighorn Medicine Wheel

High atop Medicine Mountain, an ancient circle of stones arranged with precise intention has witnessed centuries of human reverence.

The wheel measures 80 feet in diameter with 28 spokes radiating from a central cairn to an outer rim of rocks.

Archaeological evidence suggests the structure was built between 300 and 800 years ago, though some theories place it much older.

Multiple Native American tribes including the Crow, Shoshone, and Arapaho consider this location sacred, continuing ceremonial use today.

The exact purpose remains debated among scholars, with theories ranging from astronomical observatory to ceremonial gathering place.

Some alignments appear to mark summer solstice sunrise and other celestial events, suggesting astronomical knowledge.

The elevation of 9,642 feet places the wheel above treeline with panoramic views extending over a hundred miles on clear days.

Snow covers the site for much of the year, with access typically limited to late June through September.

The Forest Service maintains a respectful distance with parking and viewing areas, protecting the wheel while allowing visitation.

Visitors are asked to observe from designated areas rather than walking on or disturbing the ancient stones.

The site continues to function as an active place of prayer and ceremony for Native peoples.

Prayer bundles, tobacco ties, and other offerings often appear near the wheel, evidence of ongoing spiritual practices.

The combination of archaeological mystery, cultural significance, and spectacular mountain setting creates a powerful experience.

Locals respect the wheel’s sacred nature while appreciating the privilege of having such a remarkable site within their region.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.