Virginia holds a treasure trove of history that goes far beyond the famous stories taught in classrooms.

Hidden within its landscapes are sites that reveal the real experiences of enslaved people, Native Americans, and African American communities who shaped the nation.

These places offer honest, powerful glimpses into early America’s complex past, bringing voices and stories to light that were long ignored.

From presidential estates to historic neighborhoods, each location invites you to discover a side of history that textbooks often skip.

1. James Madison’s Montpelier

Standing on the grounds of Montpelier, you witness where one of America’s most important founders lived and worked.

James Madison helped write the Constitution, yet his estate tells a story that goes much deeper than political achievements.

Located at 11350 Constitution Highway, this historical landmark in Orange, Virginia, now offers visitors a chance to confront the contradictions of America’s founding era.

The “Mere Distinction of Colour” exhibition takes center stage here, exploring how Madison championed freedom while simultaneously enslaving people.

Walking through the exhibit, you encounter personal stories of the enslaved community who built and maintained this grand estate.

Their names, their work, and their resistance are finally being recognized and honored.

Montpelier’s restoration efforts have uncovered the living quarters and workspaces of enslaved individuals, giving physical form to their presence.

These discoveries connect visitors directly to the daily realities faced by those who lived in bondage.

The site doesn’t shy away from difficult truths.

Instead, it uses historical research and archaeological evidence to create a complete picture of plantation life.

You learn about the skills, traditions, and resilience of the enslaved community, not just their suffering.

Montpelier serves as a powerful reminder that understanding our nation’s founding requires acknowledging everyone who contributed to it.

The experience challenges visitors to think critically about liberty, equality, and who truly benefited from early American ideals.

This Virginia landmark transforms how we view one of our most celebrated presidents and the era he helped define.

2. Historic Jamestowne

Archaeological discoveries continue to reshape what we know about America’s first permanent English settlement.

Historic Jamestowne, located at 1368 Colonial National Historical Parkway, reveals far more than the traditional colonist narrative.

The site preserves where three distinct cultures collided in ways that forever changed the continent.

English settlers arrived seeking fortune and new opportunities, but they encountered established Native American communities with rich traditions.

Meanwhile, enslaved Africans from West Central Africa were forcibly brought to these shores, adding another layer to this complex story.

Excavations at the site have unearthed artifacts that tell stories textbooks often overlook.

Tools, pottery, and personal items reveal daily life for all three groups who lived and struggled here.

The archaeological museum displays these findings alongside interpretive exhibits that explain their significance.

Living history demonstrations bring the past to life, showing how people from different backgrounds interacted, traded, and sometimes fought.

You witness recreations of Native American lifeways that existed long before European arrival.

The site also explores the harsh realities of early colonization, including the Starving Time and conflicts with Powhatan peoples.

Interpreters share perspectives from all sides, creating a more balanced understanding of this pivotal moment.

Jamestown wasn’t just about English ambition.

It was a meeting point where cultures clashed, adapted, and influenced each other in profound ways.

Visiting Historic Jamestowne means confronting uncomfortable truths about colonization, displacement, and enslavement that shaped Virginia and the entire nation.

3. George Washington’s Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon presents a side of George Washington that many Americans never learned in school.

The estate at 3200 Mount Vernon Memorial Highway showcases not just the first president’s life, but the lives of the hundreds who labored there in bondage.

Over three hundred enslaved individuals built and operated this sprawling plantation.

The “Lives Bound Together” exhibit tells their stories with dignity and detail, revealing names, relationships, and daily experiences.

You discover that Mount Vernon functioned because of skilled craftspeople, field workers, cooks, and house servants who had no freedom.

Walking through reconstructed slave quarters, you gain insight into the cramped, difficult conditions they endured.

The exhibit doesn’t just focus on hardship, though.

It highlights the skills, family bonds, and small acts of resistance that defined the enslaved community.

Some individuals managed to maintain cultural traditions, pass down knowledge, and create moments of joy despite their circumstances.

The contrast between Washington’s elegant mansion and the stark quarters of those he enslaved is impossible to ignore.

Mount Vernon’s interpretation has evolved significantly, now prioritizing these untold narratives.

Special tours focus exclusively on slavery at the estate, guided by historians who have researched individual lives.

You learn about people like William Lee, Washington’s personal servant, and Ona Judge, who escaped to freedom.

Their stories add complexity to our understanding of the founding era.

Mount Vernon demonstrates that you cannot separate Washington’s achievements from the enslaved labor that made them possible.

4. First Baptist Church

Beneath the streets of Williamsburg lies physical evidence of extraordinary courage and faith.

First Baptist Church at 727 Scotland Street represents one of the oldest African American congregations in the region.

Archaeological excavations are now uncovering the foundations of this historic church, revealing stories of defiance and community.

During the eighteenth century, laws prohibited enslaved people from gathering for worship.

Despite these restrictions and the threat of punishment, this congregation met in secret.

Their determination to practice their faith and maintain community ties speaks to incredible resilience.

The current congregation has partnered with archaeologists to explore their church’s origins.

This collaboration ensures that descendant voices guide how history is interpreted and shared.

Excavations have revealed building materials, personal items, and structural remains that date back centuries.

Each artifact helps piece together how this community worshipped, organized, and persisted through oppression.

The church served as more than a place of worship.

It functioned as a center for education, mutual aid, and social connection among free and enslaved African Americans.

Leaders within the congregation risked their safety to provide spiritual guidance and practical support.

Visiting this site connects you to a tradition of faith-based resistance that helped sustain African American communities.

The ongoing archaeological work continues to reveal new details about early Black religious life in Virginia.

First Baptist Church stands as a testament to the power of community and belief in the face of systematic oppression.

5. Monticello

Thomas Jefferson’s mountaintop estate embodies the contradictions at the heart of American history.

Monticello, located at 1050 Monticello Loop in Charlottesville, showcases architectural brilliance built entirely through enslaved labor.

Jefferson wrote eloquently about liberty while holding hundreds of people in bondage throughout his lifetime.

The specialized slavery tours at Monticello confront this paradox directly, exploring the lives of those who made Jefferson’s lifestyle possible.

One of the most powerful exhibits focuses on Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman who had a decades-long relationship with Jefferson.

The “Life of Sally Hemings” exhibition examines her life with sensitivity and historical rigor.

DNA evidence and historical records have confirmed that Jefferson fathered at least six of her children.

Yet Hemings herself left no written account, making her story one that must be pieced together from fragments.

The exhibit explores what life would have been like for her, caught between enslavement and intimacy with one of America’s most powerful men.

You learn about the Hemings family, who held specialized positions at Monticello and had complex relationships with the Jefferson family.

Tours also highlight the broader enslaved community who worked in fields, workshops, and the main house.

Their skills ranged from blacksmithing to textile production, yet they received no compensation or freedom.

Monticello’s interpretation has transformed in recent years, dedicating significant space and resources to telling these stories.

The site challenges visitors to reconsider Jefferson’s legacy through a more complete lens that includes the people he enslaved.

6. Old Town Alexandria

Cobblestone streets and historic buildings in Old Town Alexandria hide stories that shaped the city’s character.

This charming neighborhood in Alexandria, Virginia, has deep roots in African American history that guided walks now bring to light.

Black residents were essential to the city’s development from its earliest days, working as laborers, craftspeople, and entrepreneurs.

Yet traditional historical narratives often overlooked their contributions and experiences.

Specialized tours through Old Town focus on sites connected to Black history, from former slave markets to churches that served as community anchors.

You walk past buildings where enslaved people were bought and sold, confronting the brutal reality of the domestic slave trade.

Alexandria was a major hub for this trade, with thousands of people passing through its auction blocks.

The tours also highlight places of resistance and achievement within the Black community.

Churches, schools, and businesses established by African Americans created networks of support and progress.

Free Black residents navigated restrictive laws while building lives and contributing to the city’s economy.

After emancipation, the community continued to grow and thrive despite segregation and discrimination.

Guides share stories of individuals whose names deserve recognition alongside more famous historical figures.

You learn about educators, activists, and everyday people who shaped Alexandria’s identity.

Old Town’s beauty is enhanced when you understand the full scope of who built it and called it home.

These walking tours transform how visitors see this historic district, adding depth and truth to its picturesque facade.

7. American Civil War Museum at Historic Tredegar

Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works once produced weapons for the Confederacy, but today it tells a much broader story.

The American Civil War Museum at 480 Tredegar Street takes a groundbreaking approach to interpreting this defining conflict.

Rather than focusing solely on battles and generals, the museum presents the war through multiple perspectives.

Union soldiers, Confederate soldiers, and African Americans all experienced the war differently, and the museum honors each viewpoint.

Exhibits use personal stories, letters, and artifacts to humanize the conflict’s complexity.

You encounter accounts from enslaved people who escaped to Union lines, seeking freedom behind advancing armies.

Their testimonies reveal the war’s meaning to those who had the most to gain from Union victory.

Confederate perspectives are presented without glorification, examining why individuals fought and how they justified their cause.

Union soldiers’ experiences highlight the evolution of the war’s purpose, from preserving the nation to ending slavery.

The museum doesn’t shy away from difficult questions about memory, monuments, and how the war is remembered today.

Interactive displays encourage visitors to think critically about historical interpretation and whose stories get told.

African American voices receive particular emphasis, recognizing that the war fundamentally concerned their freedom and future.

You learn about Black soldiers who fought for the Union, despite facing discrimination within the military itself.

The museum’s location in the former Confederate capital adds another layer of significance to its mission.

By presenting multiple perspectives, it creates space for honest conversation about the war’s causes, conduct, and consequences.

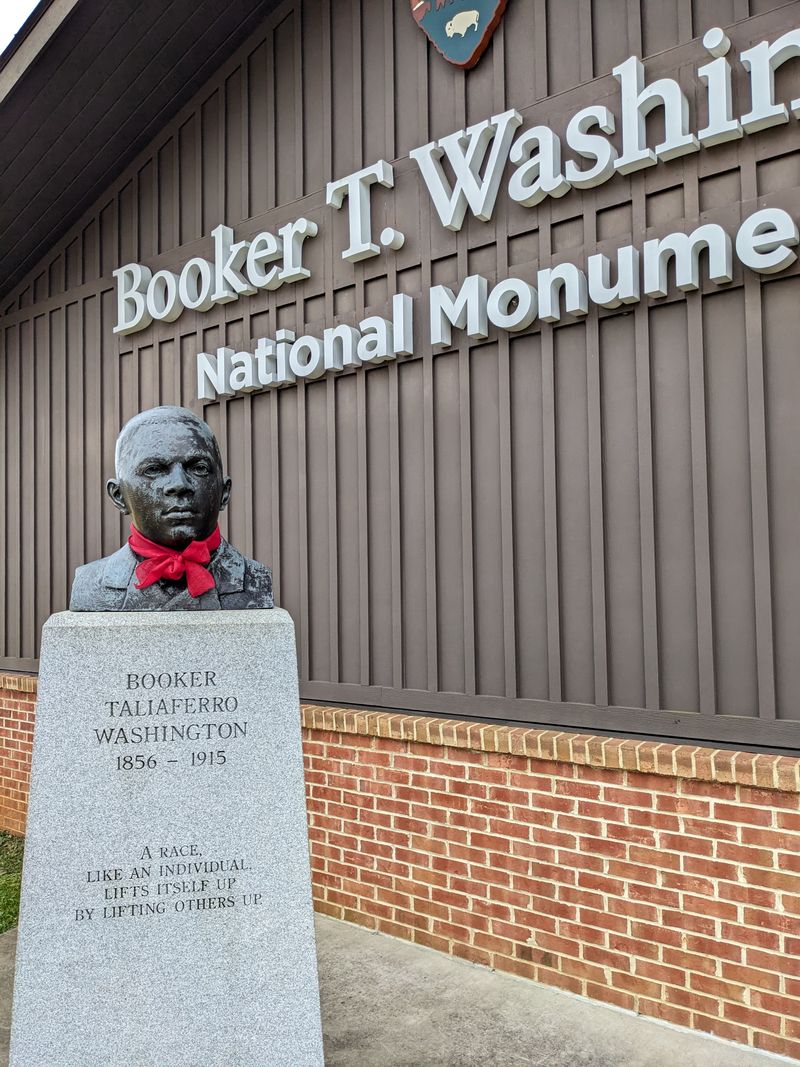

8. Booker T. Washington National Monument

Born into slavery on a small Virginia plantation, Booker T.

Washington became one of America’s most influential educators.

The national monument at 12130 Booker T Washington Highway preserves the site of his birth and early childhood.

Visiting here means stepping into the world of an enslaved child during the Civil War era.

The reconstructed farm buildings and living quarters show the harsh conditions Washington endured as a boy.

He slept on dirt floors, wore rough clothing, and worked from an early age despite his youth.

Yet even in these circumstances, Washington developed a hunger for education that would define his life.

The site explores how enslaved children experienced bondage differently than adults, often separated from parents and denied basic nurturing.

Washington’s mother worked as a cook, and he rarely saw his father, who may have been a white man from a nearby plantation.

After emancipation, Washington’s family moved to West Virginia, where he worked in salt furnaces and coal mines.

His determination to learn led him to walk hundreds of miles to attend Hampton Institute, beginning his educational journey.

The monument traces this remarkable transformation from enslaved child to founder of Tuskegee Institute.

Rangers and interpreters share Washington’s story alongside broader context about slavery’s end and Reconstruction’s challenges.

You gain insight into how formerly enslaved people pursued education despite enormous obstacles.

Washington’s life demonstrates the resilience and ambition that characterized many who emerged from bondage seeking better futures.

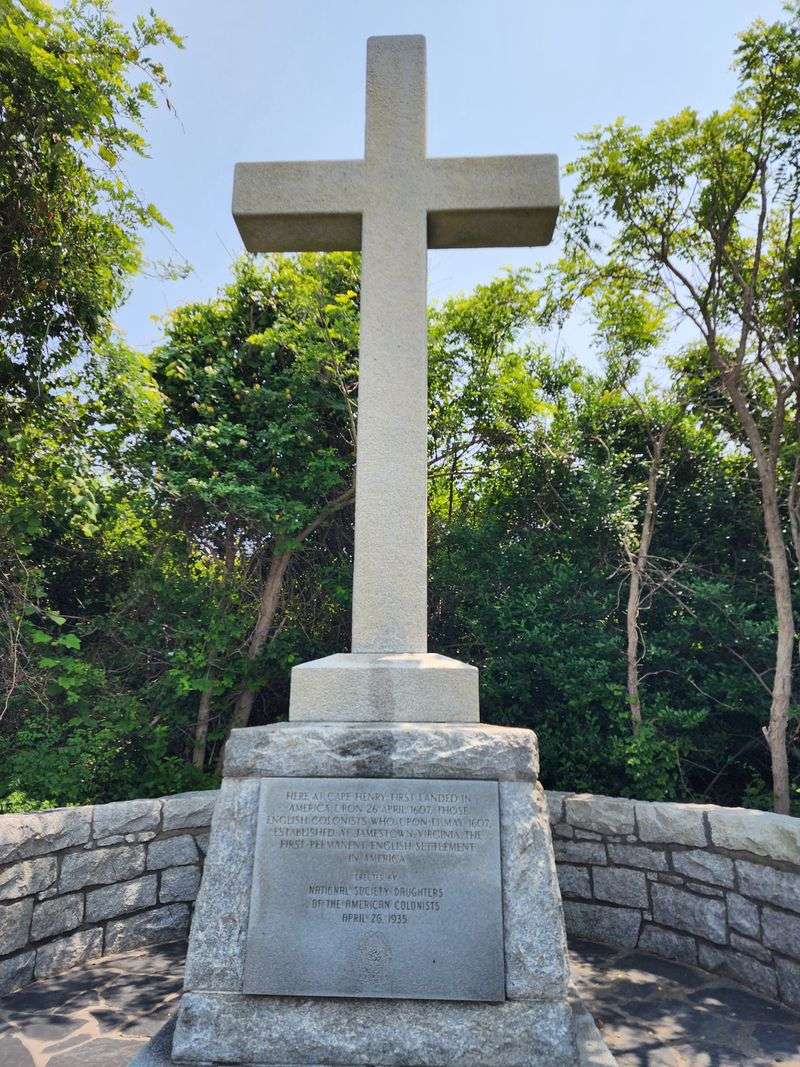

9. Cape Henry Memorial Cross

Where the Chesapeake Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean, a cross marks the first landing of English colonists in what would become Virginia.

Cape Henry Memorial commemorates this moment from colonial history, but the site holds another important story.

During the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps built facilities throughout American parks and monuments.

An all-Black CCC company constructed buildings and infrastructure at Cape Henry, providing jobs during desperate economic times.

These young African American men worked alongside other CCC units, performing the same labor and contributing equally to conservation efforts.

However, segregation laws prevented them from using the very facilities they built.

After completing their work, they were barred from beaches, picnic areas, and recreational spaces that white visitors enjoyed freely.

This contradiction reflects the broader reality of the Jim Crow era, when Black Americans contributed to society while being denied full participation.

The CCC provided valuable work experience and income for Black families during the Depression, but always within a segregated system.

Acknowledging this history at Cape Henry adds complexity to the site’s interpretation.

The memorial isn’t just about colonial exploration anymore.

It also represents the contributions and exclusion of African American workers who shaped the landscape decades later.

Visitors can reflect on how different groups experienced the same location across centuries.

Cape Henry reminds us that history happens in layers, with each generation adding new meaning to old places.

10. Jackson Ward

Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood earned nicknames that reflected its remarkable success and cultural vibrancy.

Known as both Black Wall Street and the Harlem of the South, this historic district became a center of African American achievement.

Following the Civil War, Black residents built a thriving community despite the constraints of segregation.

Banks, insurance companies, theaters, and shops lined the streets, all owned and operated by African Americans.

This economic independence created opportunities that were rare for Black communities in the Jim Crow South.

Maggie L.

Walker stands out as one of Jackson Ward’s most notable residents.

She became the first female bank president in United States history, leading the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank.

Her home, now a National Historic Site, offers tours that explore her life and contributions.

Walker’s success inspired others and demonstrated what Black entrepreneurship could achieve even under oppressive conditions.

Jackson Ward’s architecture reflects the prosperity its residents built, with elegant rowhouses and commercial buildings still standing.

The neighborhood also nurtured musicians, writers, and performers who contributed to American culture.

Jazz clubs and theaters drew crowds, creating a vibrant nightlife that rivaled larger cities.

Urban renewal projects in the mid-twentieth century damaged Jackson Ward, cutting highways through its heart.

Yet the neighborhood has persisted, and recent preservation efforts work to honor its history.

Walking through Jackson Ward today means witnessing the legacy of a community that refused to be limited by discrimination.

11. Moore House

Tucked away in Yorktown, an unassuming colonial home witnessed one of history’s most significant moments.

Moore House at 228 Nelson Road served as the location where British officers negotiated surrender terms ending the Revolutionary War.

General Cornwallis’s representatives met with American and French officers inside this modest structure.

The negotiations determined how British forces would lay down their arms and what would happen to soldiers and supplies.

Without this meeting, the Battle of Yorktown’s military victory might not have translated into war’s end.

The house itself reflects typical Virginia plantation architecture of the period, built for comfort rather than grandeur.

Its rooms have been preserved to show how they appeared during those fateful discussions.

You can stand in the very space where officers debated terms that would birth a new nation.

The surrender negotiations took place over several days, with both sides carefully considering every detail.

American negotiators insisted on terms that respected their new nation’s dignity while the British sought to preserve their honor in defeat.

The resulting agreement allowed British troops to march out with military honors, though they had to surrender their weapons.

Moore House represents a quieter kind of historical site, where words and diplomacy proved as important as battlefield victories.

The negotiations held here effectively ended British attempts to suppress American independence.

Visiting this unpretentious home offers perspective on how wars conclude, not just with final battles but with careful political agreements.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.