Let’s be real, New Jersey speaks its own language. And no, I don’t just mean the honking.

Between two massive cities, a legendary coastline, and traffic patterns that could make anyone lose their mind, Jersey slang is basically a survival skill.

The way you order breakfast meat or describe a trip to the beach instantly gives away where you grew up – North Jersey with its New York lean, South Jersey with Philly vibes, and the middle? Don’t even get me started, that’s a whole debate in itself.

Here’s the fun part: locals treat certain phrases like secret passwords. Say the wrong thing at a diner or butcher a town name, and boom – outsider status.

These words run deep, passed down through families who’ve never left their exit number. It’s like a cultural fingerprint, and trust me, you can’t fake it.

So the question is: do you actually speak Jersey, or are you just visiting?

Buckle up, because these 15 words and phrases will separate the true locals from the bennies faster than you can merge onto the Parkway, and yes, that merge is terrifying.

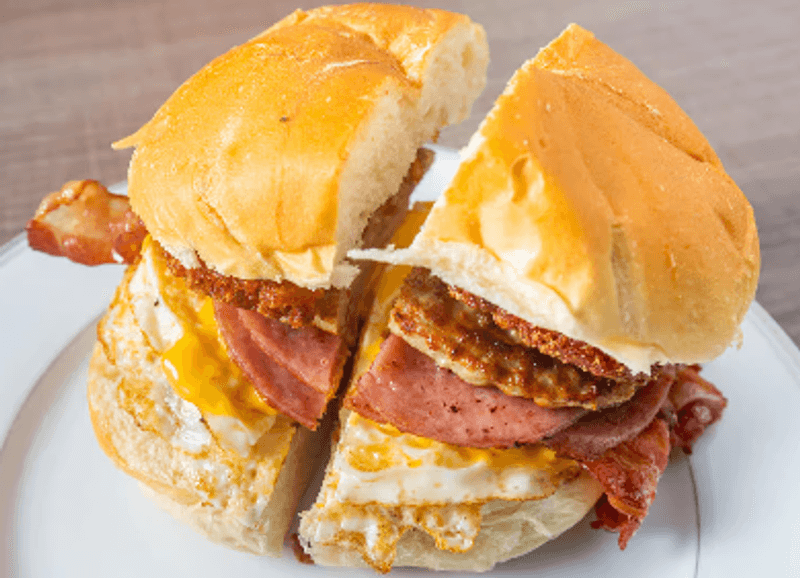

Pork Roll vs. Taylor Ham

Nothing divides New Jersey more fiercely than what you call that circular breakfast meat sitting between your egg and cheese. North Jersey residents swear by “Taylor Ham,” named after the original brand created by John Taylor in 1856.

South and Central Jersey folks insist it’s “Pork Roll,” sticking to the generic product name that appears on most packaging today. This isn’t just a preference; it’s a geographical identity marker that locals take seriously.

Walk into any diner and order using the wrong term for your region, and you’ll get knowing looks from everyone at the counter. The debate has inspired countless social media arguments, t-shirts, and even academic discussions about regional linguistics.

Some restaurants diplomatically list both names on their menus to avoid taking sides. The state legislature has never officially settled the matter, leaving New Jerseyans to battle it out one breakfast sandwich at a time.

The controversy goes beyond simple naming conventions because it reflects deeper cultural divisions between North and South Jersey. Northern residents align with New York City influences, while southerners lean toward Philadelphia traditions.

Central Jersey residents often use both terms interchangeably, which only adds fuel to the fire. Food historians note that Taylor originally called his product “Taylor’s Prepared Ham” before a legal ruling forced the name change to “Pork Roll” in 1906.

Regardless of what you call it, this salty, savory meat remains a Garden State staple found in diners, delis, and home kitchens throughout every county. The crispy edges, the way it cups when cooked, and that unmistakable flavor make it irreplaceable to locals who grew up eating it weekly.

Hoagie vs. Sub

Another battle line gets drawn when New Jersey residents order a long sandwich stuffed with cold cuts, cheese, lettuce, tomatoes, and oil. South Jersey natives call it a “hoagie,” borrowing directly from Philadelphia vocabulary where the term originated on Hog Island during World War I.

North Jersey folks say “sub” or “submarine sandwich,” reflecting New York City’s influence on their regional dialect. This linguistic split mirrors the state’s eternal identity crisis between two major metropolitan areas.

Ordering at a sandwich shop immediately reveals your geographic origins and cultural allegiances. Wawa locations in South Jersey prominently feature “hoagies” on their menu boards, while North Jersey delis advertise “heroes” or “subs” instead.

The terminology extends beyond casual conversation into restaurant names, with establishments branding themselves according to their regional location. Some Central Jersey residents use both terms depending on their audience, adding another layer of complexity.

The divide reflects decades of cultural influence from neighboring cities that have shaped everything from food vocabulary to sports team loyalties. Philadelphia’s hoagie tradition dates back nearly a century, with annual Hoagiefest celebrations and dedicated shops perfecting the art.

Meanwhile, New York’s submarine sandwich culture developed separately, creating distinct preparation styles and ingredient preferences. New Jersey sits squarely in the middle, absorbing both traditions and creating its own hybrid identity.

Interestingly, some Shore towns use different terms depending on whether summer tourists or year-round residents are ordering. Smart deli owners train their staff to recognize both terms and respond accordingly.

The sandwich itself remains essentially the same regardless of name, though purists argue about proper ingredient ratios, bread texture, and whether mayo belongs anywhere near an authentic version.

Sprinkles vs. Jimmies

Ice cream toppings become a linguistic battlefield when South Jersey residents ask for “jimmies” while everyone else requests “sprinkles.” This peculiar regional term appears primarily in Philadelphia-influenced areas of New Jersey, though its exact origins remain hotly debated among food historians. Some claim the name came from the Just Born candy company in the 1930s, while others trace it to earlier confectionery traditions.

Regardless of etymology, saying “jimmies” immediately identifies you as someone from the southern portion of the Garden State.

North Jersey ice cream shops rarely use this term, sticking instead to the more universal “sprinkles” that most Americans recognize. The terminology applies specifically to chocolate sprinkles in traditional usage, though some South Jersey natives use it for rainbow varieties as well.

Boardwalk ice cream stands along the Shore often list both terms on their menus to accommodate tourists and locals alike. Shore town workers can usually guess where you’re from based solely on which word you use when ordering.

The debate occasionally takes uncomfortable turns when people incorrectly assume the term has racial origins, though food historians have thoroughly debunked such claims. The word simply reflects regional vocabulary variations similar to “soda” versus “pop” or “sneakers” versus “tennis shoes.” South Jersey children grow up hearing “jimmies” from parents and grandparents, passing the term through generations without questioning its unusual nature.

Moving to North Jersey or leaving the state often means abandoning the term to avoid constant explanations.

Ice cream shops in Central Jersey sometimes face confusion when customers from different regions use competing terminology. Smart shop owners train their staff to understand both terms and respond naturally.

The sprinkles themselves taste identical regardless of what you call them, though locals swear their childhood ice cream memories are forever tied to specific vocabulary.

Soda vs. Pop

Ask any true New Jersey resident what they call a carbonated soft drink, and the answer will almost universally be “soda.” This distinguishes Garden State natives from Midwesterners who say “pop” or Southerners who call everything “Coke” regardless of brand. The terminology remains consistent across North, Central, and South Jersey, making it one of the few linguistic elements that unifies the entire state.

Saying “pop” in a New Jersey diner will immediately mark you as an outsider, prompting curious looks and questions about where you’re originally from.

The consistency of this term reflects New Jersey’s position between two major cities that both use “soda” as their standard vocabulary. Philadelphia and New York City residents have used this term for generations, and New Jersey naturally absorbed the same linguistic pattern.

Regional dialect maps of the United States show New Jersey firmly planted in “soda” territory, surrounded by similar usage patterns throughout the Northeast corridor. The term appears on diner menus, convenience store signs, and in everyday conversation without variation.

Linguists studying American regional dialects often point to beverage terminology as one of the clearest markers of geographic origin. The “soda” versus “pop” divide roughly follows the Appalachian Mountains, with Eastern states preferring “soda” and many Midwestern states using “pop.” New Jersey’s unwavering commitment to “soda” demonstrates its strong cultural ties to the Eastern Seaboard rather than inland regions.

Even New Jersey residents who move to “pop” states often stubbornly maintain their original terminology.

Restaurants and diners throughout the Garden State list “soda” on their menus without considering alternatives. Fountain drinks, bottled beverages, and canned drinks all fall under this umbrella term.

The consistency extends to advertising, with local commercials and radio spots using “soda” exclusively when marketing soft drinks to New Jersey audiences.

Down the Shore

New Jersey locals never say they’re going “to the beach” because that phrase sounds foreign and imprecise to Garden State ears. Instead, everyone heads “down the shore” regardless of which direction they’re actually traveling from their home.

North Jersey residents drive south to reach the ocean, yet they still use the same “down the shore” phrasing as everyone else. This unique expression has defined New Jersey summer culture for generations, appearing in conversations, songs, and even official tourism marketing campaigns.

The phrase encompasses more than just the sandy beach itself, referring to the entire coastal experience including boardwalks, beach towns, rental houses, and summer communities. Families plan their annual “shore house” rentals months in advance, securing the same properties year after year in towns like Seaside Heights, Cape May, or Long Beach Island.

The expression carries emotional weight, evoking memories of childhood summers, first crushes on the boardwalk, and family traditions passed through generations. Saying “the beach” instead immediately identifies you as someone unfamiliar with New Jersey culture.

The terminology extends into related phrases like “shore house,” “shore traffic,” and “shore season,” all carrying specific meanings to locals. Memorial Day weekend marks the unofficial start of shore season, when beach towns transform from quiet winter communities into bustling summer destinations.

Labor Day signals the end, though many locals prefer visiting during the quieter shoulder seasons. The Garden State Parkway becomes a parking lot every summer weekend as thousands of families make their pilgrimage down the shore.

Even New Jersey residents who live inland and rarely visit the coast understand and use this terminology. The phrase appears in local music, literature, and popular culture, cementing its place in Garden State identity.

Television shows set in New Jersey inevitably feature shore episodes, and the term “down the shore” needs no explanation for anyone who grew up here.

The City

When New Jersey residents mention “The City,” they’re not talking about their own municipality or even the state capital of Trenton. Depending on which part of New Jersey you call home, “The City” refers exclusively to either New York City or Philadelphia.

North Jersey residents automatically mean Manhattan when they say they’re heading into “The City” for dinner or a show. South Jersey folks use the identical phrase but mean Philadelphia instead, creating potential confusion when residents from different regions have conversations.

This linguistic quirk reveals New Jersey’s unique position as a state without a dominant urban center of its own. Newark, Jersey City, and other Garden State cities never earn the definite article treatment because they can’t compete with the gravitational pull of their neighboring metropolises.

The phrase comes so naturally to locals that many don’t realize how strange it sounds to outsiders. Saying “I’m going to the city this weekend” requires no clarification among people from the same region because everyone understands the implied destination.

The dividing line roughly follows the Driscoll Bridge on the Garden State Parkway, though Central Jersey residents sometimes use the phrase for whichever city they’re visiting. North Jersey residents maintain strong cultural, economic, and social ties to New York, with many commuting daily for work.

South Jersey shares similar connections with Philadelphia, with residents following Philly sports teams and adopting Pennsylvania vocabulary. This dual identity means New Jersey never developed a singular urban identity of its own.

The phrase extends beyond casual conversation into business discussions, weekend plans, and cultural references. Teenagers talk about concerts in “The City,” professionals discuss job opportunities there, and families plan holiday shopping trips.

The terminology reflects decades of commuter culture and economic integration between New Jersey and its more famous neighbors.

Jug Handle

Few traffic features confuse out-of-state drivers more than New Jersey’s infamous jug handles, those bizarre curved ramps that force you to turn right in order to eventually turn left. These distinctive roadway designs appear throughout the Garden State, particularly along major highways and busy commercial corridors.

The name comes from the shape of the ramp, which resembles the handle of a jug when viewed from above. Locals navigate these intersections without thinking, while tourists and new residents often miss their turns entirely, circling back in frustration.

The engineering logic behind jug handles involves reducing left-turn conflicts at busy intersections, theoretically improving traffic flow and safety. Instead of waiting in the main travel lanes to turn left across oncoming traffic, drivers exit to the right, follow the curved ramp, and approach the cross street from a different angle.

Some jug handles deposit you directly onto the cross street, while others place you at a traffic light where you can proceed straight through. New Jersey has more of these peculiar intersections than anywhere else in America, making them a distinctive feature of Garden State driving.

Learning to navigate jug handles represents a rite of passage for new New Jersey residents and teenage drivers. Missing your jug handle exit often means traveling miles out of your way before finding another opportunity to turn around.

GPS systems sometimes struggle to provide clear instructions for these intersections, adding to the confusion. Locals develop an instinctive understanding of which intersections feature jug handles and plan their lane positioning accordingly well in advance.

The term “jug handle” itself rarely appears on official signage, existing primarily in local vocabulary and informal directions. Residents giving directions will casually mention “take the jug handle” without considering that outsiders might not understand the reference.

Some intersections feature multiple jug handles serving different directions, creating additional complexity for unfamiliar drivers.

Circles

Traffic circles in New Jersey inspire equal parts dread and grudging acceptance among drivers who navigate them regularly. These circular intersections predate modern roundabouts, featuring different traffic patterns and often larger diameters that can accommodate significant vehicle volumes.

The Brooklawn Circle near the Walt Whitman Bridge and the former Flemington Circle achieved legendary status among locals for their complexity and frequent backups. Unlike European roundabouts with clear yielding rules, New Jersey circles often operated with confusing right-of-way patterns that varied by location.

Many of New Jersey’s most notorious circles have been eliminated in recent years, replaced by conventional intersections or modern roundabouts with clearer traffic rules. However, several remain in operation, and locals still refer to these locations by their historic circle names even after reconstruction.

The term “circle” in New Jersey carries specific connotations different from the more generic “roundabout” used in other states. Residents who learned to drive navigating these circles often share war stories about close calls and confusing merges.

The love-hate relationship New Jersey drivers maintain with circles stems from their unpredictable nature and the aggressive driving style often required to successfully merge. Some circles featured traffic lights within the circular roadway, creating hybrid intersections that confused even experienced drivers.

Others operated on a free-for-all basis where assertiveness determined success. The phrase “going around the circle” appears frequently in local directions, with specific circles serving as landmarks and meeting points.

Despite their declining numbers, circles remain embedded in New Jersey’s cultural consciousness and local vocabulary. Radio traffic reports still reference circle locations, and residents use them as geographic reference points when giving directions.

The unique challenges of circle navigation created a shared experience among Garden State drivers, bonding them through mutual frustration and hard-won expertise.

Parkway vs. Turnpike

New Jersey residents identify their geographic location by exit numbers rather than town names, a quirk that baffles outsiders but makes perfect sense to locals. The Garden State Parkway and New Jersey Turnpike serve as the state’s primary north-south arteries, and their numbered exits function as a statewide address system.

Saying “I’m Exit 98” on the Parkway instantly tells other locals you’re from the Asbury Park area, while “Exit 8A” on the Turnpike places you near the Jersey Shore outlets. This system works because most New Jersey residents regularly travel these highways and have internalized the exit numbers for major destinations.

The two highways serve different purposes and carry distinct reputations among drivers. The Garden State Parkway charges lower tolls and generally offers more scenic views, passing through residential areas and shore communities.

The New Jersey Turnpike handles heavier truck traffic and provides faster travel times for long-distance trips, though at higher toll costs. Locals debate which route offers better value for specific journeys, with preferences often depending on final destination and time of day.

Both highways suffer from legendary traffic congestion, inspiring countless complaints and creative alternate route strategies.

The exit number system occasionally causes confusion because both highways have undergone renumbering projects over the decades. Longtime residents still reference old exit numbers that were changed years ago, while newer residents use current numbering.

Some exits serve multiple towns, while others provide access to relatively obscure locations. The system works best for people who have lived in New Jersey long enough to build mental maps connecting exit numbers to actual places.

Using exit numbers as location identifiers extends beyond casual conversation into real estate listings, business addresses, and event directions. The highways themselves earn shortened names in local speech, with “the Parkway” and “the Turnpike” requiring no additional explanation.

Twenty Regular

New Jersey stands as one of only two states where pumping your own gas remains illegal, a quirk that has shaped local vocabulary and customer interactions for decades. The phrase “twenty regular” represents the standard request New Jersey drivers make to gas station attendants, asking for twenty dollars worth of regular unleaded gasoline.

This exchange happens thousands of times daily across the Garden State, creating a unique ritual unfamiliar to drivers from self-service states. The law requiring attendant service dates back to 1949, originally justified by safety concerns that have long since been addressed in other states.

The phrase itself reflects an era when twenty dollars bought significantly more gasoline than it does today, though the terminology persists even as fuel prices fluctuate. Some drivers specify dollar amounts, while others request “fill it up” for a full tank.

The attendant service includes not just pumping gas but also cleaning windshields at some stations, though this extra service has become less common over time. New Jersey residents traveling out of state often experience brief confusion when confronted with self-service pumps, sometimes sitting in their cars waiting for attendants who will never arrive.

The law generates ongoing debate among New Jersey residents, with some appreciating the convenience and job creation while others resent the slower service and inability to pump their own gas. During busy periods, waiting for an available attendant can add significant time to a fuel stop.

However, the system provides employment for thousands of workers and allows drivers to remain in their vehicles during inclement weather. The phrase “twenty regular” has become so ingrained in New Jersey culture that it appears in local comedy routines and social media posts.

Gas stations throughout New Jersey employ attendants who have perfected the efficient choreography of serving multiple vehicles simultaneously. The interaction follows a predictable pattern, with drivers rolling down windows, stating their request, and providing payment before the attendant begins pumping.

Benny

Shore town locals use “benny” as a mildly derogatory term for tourists from North Jersey and New York City who flood coastal communities every summer weekend. The acronym supposedly stands for Bayonne, Elizabeth, Newark, and New York, though this origin story may be folk etymology rather than historical fact.

Regardless of its true origins, the term carries unmistakable meaning along the Jersey Shore, where year-round residents develop complicated relationships with the summer visitors who sustain local economies while also creating traffic jams, crowded beaches, and occasionally disrespectful behavior.

The benny stereotype involves loud groups, expensive cars, designer sunglasses, and a general unfamiliarity with beach town etiquette. Shore locals can supposedly spot bennies from their license plates, driving habits, and the way they set up elaborate beach camps with excessive equipment.

The term gets used both affectionately and with genuine frustration, depending on context and the speaker’s mood. Summer weekends transform quiet shore towns into bustling tourist destinations, with bennies providing the customer base that keeps restaurants, shops, and attractions profitable during peak season.

The economic reality complicates the relationship because shore towns depend heavily on tourism revenue to survive financially. Local businesses cater to benny preferences while year-round residents sometimes avoid downtown areas during summer weekends.

The term appears in local bar conversations, social media posts, and even on novelty t-shirts sold in shore town shops. Some visitors embrace the label ironically, while others take offense at being stereotyped.

The dynamic reflects broader tensions between tourist destinations and the communities that host them.

Shore town natives develop strategies for coexisting with summer crowds, including shopping and running errands during weekday mornings when bennies are still at the beach. The term serves as linguistic shorthand for a complex set of cultural and economic relationships that define New Jersey shore life.

Shoobie

South Jersey shore communities have their own version of “benny” called “shoobie,” referring to day-trippers from Philadelphia who historically brought their lunches in shoe boxes to avoid spending money at local establishments. The term carries similar connotations of tourists who visit shore towns without fully respecting or understanding local culture.

While the shoe box lunch tradition has largely disappeared, the vocabulary persists in places like Ocean City, Wildwood, and Cape May. Shoobies typically arrive early in the morning, stake out beach territory, and depart before sunset, minimizing their economic contribution to local businesses.

The distinction between shoobies and bennies reflects the geographic and cultural divide between North and South Jersey. Philadelphia-area visitors head to southern shore destinations, while New York-area tourists prefer northern beaches, creating separate tourist ecosystems with their own terminology.

Local shore residents in South Jersey use “shoobie” with the same mixture of affection and exasperation that northern shore towns reserve for bennies. The term appears less frequently in modern usage compared to previous generations, though older residents and longtime locals still employ it regularly.

Shore town economies in South Jersey depend on Philadelphia-area visitors just as northern shore towns rely on New York tourists. The shoobie dynamic involves similar tensions between year-round residents and seasonal visitors, with locals navigating crowded streets and beaches during summer months.

Some South Jersey shore towns have attempted to attract overnight visitors rather than day-trippers, investing in hotels and vacation rentals to encourage longer stays and greater spending. The terminology reflects class distinctions as well as geographic ones, with day-trippers perceived as less invested in shore communities than families who rent seasonal properties.

The word “shoobie” occasionally appears in local business names and marketing campaigns, reclaimed by shore towns as a playful reference to their tourist history. Despite its origins as a somewhat dismissive term, it has evolved into part of South Jersey shore identity.

D’jeet

“D’jeet?” represents the ultimate New Jersey contraction, compressing “Did you eat?” into a single slurred syllable that perfectly captures the state’s rapid-fire conversational style. This greeting appears constantly in New Jersey social interactions, particularly when friends or family members encounter each other around traditional meal times.

The expected response follows a predictable pattern: if the answer is no, the follow-up question is almost always “Wanna go to a diner?” because New Jersey’s legendary diner culture provides the natural solution to hunger at any hour.

The phrase demonstrates how New Jersey speech patterns compress and accelerate standard English into efficient verbal shortcuts. Similar constructions appear throughout local vocabulary, with phrases blending together until they become nearly unintelligible to outsiders.

The contraction works because both parties understand the implied meaning and the cultural context surrounding food and hospitality in New Jersey communities. Asking if someone has eaten serves as both a practical question and a social gesture, offering connection and potential shared experience.

New Jersey’s diner culture provides the essential backdrop for this linguistic quirk. The state boasts more diners per capita than anywhere else in America, with these chrome-plated establishments serving everything from breakfast to late-night snacks twenty-four hours a day.

Diners function as community gathering spaces, business meeting locations, and default destinations when hunger strikes. The “D’jeet” exchange often leads directly to sliding into a vinyl booth and ordering from the encyclopedic menu that defines New Jersey diner service.

The phrase appears most frequently in North Jersey, though variations exist throughout the state. Some linguists study these contractions as examples of regional dialect evolution, showing how frequently used phrases naturally compress over time.

The “D’jeet” phenomenon represents more than just lazy pronunciation; it reflects the fast-paced, no-nonsense communication style that characterizes New Jersey culture.

The Parkway

When New Jersey residents refer to “The Parkway” without additional context, everyone automatically understands they mean the Garden State Parkway, the 172-mile toll road that serves as the state’s primary north-south artery. This shortened reference reflects how deeply the highway has embedded itself into New Jersey consciousness and daily life.

Unlike other states where highway names require full articulation, New Jersey’s Parkway earns definite article status and universal recognition. The road connects nearly every major destination in the state, from the New York border down to Cape May at the southern tip.

The Parkway serves multiple functions beyond basic transportation, acting as a geographic reference system, a cultural touchstone, and a shared experience that unites New Jersey residents. Traffic reports focus heavily on Parkway conditions, with radio stations providing exit-by-exit updates during rush hours.

The highway passes through diverse landscapes, from dense urban areas in the north through suburban sprawl in central regions to the natural beauty of the Pinelands and shore approaches in the south. Locals develop intimate knowledge of specific stretches, knowing which exits offer the best rest stops, food options, and scenic views.

The term “The Parkway” appears constantly in New Jersey conversations about travel, commuting, and weekend plans. Residents give directions referencing Parkway exits and plan routes based on Parkway access points.

The highway’s distinctive blue and white signs become deeply familiar to anyone who drives regularly in New Jersey. Summer weekends bring legendary traffic jams as shore-bound vehicles pack the southbound lanes, while Sunday evenings see the reverse migration northward.

These traffic patterns have shaped New Jersey culture, with families timing shore departures to avoid the worst congestion.

The Parkway’s toll system uses electronic E-ZPass technology, though cash lanes still exist at most plazas. The highway represents a significant expense for frequent users, with tolls adding up quickly for daily commuters.

Central Jersey

Perhaps no phrase generates more passionate debate among New Jersey residents than “Central Jersey,” with people from the middle counties insisting their region exists as a distinct entity while North and South Jersey residents often claim it’s a myth. This geographic controversy has inspired countless arguments, social media battles, and even academic discussions about regional identity.

Residents of Middlesex, Monmouth, and Somerset counties particularly champion Central Jersey’s existence, arguing they share neither North Jersey’s New York orientation nor South Jersey’s Philadelphia influence. The debate reveals deeper questions about how New Jersey residents define themselves and their communities.

The argument extends beyond simple geography into cultural identity, with Central Jersey advocates pointing to unique characteristics that distinguish their region. They claim neutrality in the pork roll versus Taylor ham debate, equal access to both New York and Philadelphia, and a distinct suburban character.

Central Jersey supposedly represents the “real” New Jersey, free from the dominant influence of neighboring cities. However, North and South Jersey residents often dismiss these claims, insisting the state divides neatly into two regions with no meaningful middle ground.

The controversy has inspired maps attempting to define Central Jersey’s boundaries, though no consensus exists about where it begins and ends. Some definitions place the dividing line at the Driscoll Bridge, while others use the Raritan River or specific highway exits.

The debate occasionally turns serious when discussing political representation, media markets, and regional planning. Central Jersey advocates feel erased when people describe New Jersey as simply “North” and “South,” arguing their communities deserve recognition as a distinct region.

Using the phrase “Central Jersey” immediately signals your position in this ongoing debate. Residents from the disputed region use it proudly, while others might roll their eyes or launch into arguments about why it doesn’t exist.

The controversy has become a defining feature of New Jersey identity, representing the state’s complex relationship with its own geography and culture.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.