Discover how fuzzy llama creatures can turn camping and hiking with toddlers into a relaxing, memorable Wild West family adventure.

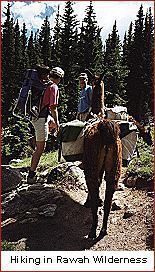

"Llamas hum!" my toddler son blurted out. Strapped into a child carrier on my husband Rich's back, Will strained to see more of the curious spectacle before him. He seemed magnetically attracted to the four long-legged, long-necked fuzzy creatures who were leading us up the trail to his first camping adventure. The llamas, my family (including our dog), the outfitter and a wrangler were all headed into the Rawah Wilderness, part of the Medicine Bow Range in the northern Colorado Rockies.

The trail hugged a swiftly flowing mountain stream engorged with snow melt that gave off cool air, which we gulped with relief after the dusty drive from the llama ranch in the foothills.

Strolling to the music of the water and the llamas' contended humming, we took a relaxed pace, shaded by a mixed tree canopy of silvery mature aspens and towering ponderosa pines.

How To Pack Gear and Toddler?

Will was not yet two, yet Rich and I, both outdoor enthusiasts in our pre-child past lives, were eager to introduce him to the joys of wilderness camping. The question had been, how to get all the gear, as well as Will and all his latter-day toddler paraphernalia including diapers, into the woods without breaking our backs (neither of us has a strong one)? The answer: llamas, the gentle sure-footed camelids native to the Andes.

Though domesticated millennia ago, llamas were only introduced to the United States in the late 19th century and weren't widely used as pack animals in North America until the 1970s. Though the horse is the prevalent pack animal in the United States, we chose llamas for two reasons.

First, we wanted to preserve our independence. Horses cannot go everywhere people on foot can, so they tend to dictate one's hiking itinerary. Llamas can go almost anywhere within reason that hikers on two feet can go.

Second, llamas cause less damage to trails than horses, whose hoofs can quickly churn up even well-packed trails, causing erosion. Llamas have two-toed, dog-like pads for feet and they are a more human-scaled animal, weighing about 325 pounds.

Llama Outfitter to the Rescue

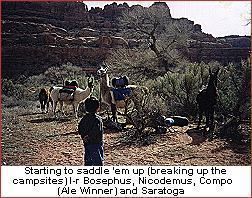

Stan Ebel, the owner of the outfitter we chose, Buckhorn Llama Company, (970/667-7411) located at 7220 North County Rd 27, Loveland, Colorado, met us at his ranch at 8 a.m. We followed his pick-up to the trailhead, some two hours west, absorbed in watching the trailer-full of brown, white and spotted llamas, heads swaying atop their graceful curved necks in the truck's draft. Stan and a wrangler loaded our gear bags (we had picked up the saddle-bags a day before to pack them) onto two llamas. Two more, along for training, carried my daypack with lunch and Stan and the wrangler's supplies for the day.

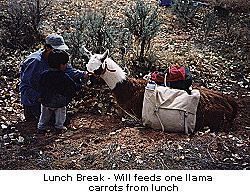

Rich and I took turns carrying Will, over a hike of seven miles and more than 2500 feet of elevation gain. Dogs sometimes spook llamas, so we stayed ahead of the pack animals, gathering together to stop for lunch where the llamas "kushed" (lay down and rested) in the shade of Engelmann spruce and browsed on the underbrush.

Llamas' gentle faces with their liquid dark eyes and long, expressive "banana" ears resemble rabbits as much as their camel brethren. With his nascent vocabulary, Will announced, "four legs", "eat grass" "llamas walk", and other astute observations for the duration of our climb upwards to camp. Although increasingly common, llamas are still an exotic sighting for many hikers in the U.S. Chatting with those who were curious gave us an excuse to rest our legs and backs, a welcome respite for whoever was carrying Will. Lugging him was sweaty gruntwork given the altitude and the steep hot trail. Including the weight of his carrier and supplies, he weighed about 35 pounds.

Climbing higher into the Rockies' sub-alpine ecosystem, the air cooled and the trees grew shorter. We hopped over puddles of snowmelt and sink deep into fresh mud. At the lower rim of two lakes called Twin Craters, still partially frozen in mid-July, we found a campsite free of snow at treeline. Moss pinks, purple forget-me-nots and tiny mountain blue-bells poked out of every square inch of earth free of snow, taking advantage of the short growing season. The ubiquitous rodent of the high country, the pika, which resembles an overgrown gerbil, greeted us with a piercing whistle. On the far side of the lake, we eyed a herd of big horn sheep, busy grazing the new grass. The Rawah Peaks towered overhead, casting long pointy shadows over the south slopes of the snow-draped glacier-carved cirque. The setting sun tinted the snow and our grubby faces gold. We helped unload the gear bags from the llamas, then bid them, Stan and the wrangler goodbye, waving as the llamas gingerly stepped across the soft snow where the trail had finally petered out.

After a hot dinner cooked on our tiny backpacking stove, we hit the sack, tired but thrilled to be living the fantasy we had looked forward to for so long. Outside the tent, our dog Osa kept the marmots at bay. These denizens of the western mountains are known to be aggressive raiders of campers' food supplies. The most impressive company, besides the wildlife, was an Outward Bound group of 12, practicing their snow technique above the lakes.

Fishing, Climbing & Napping in the Snow

Crossing a snowfield the next day on our way to a small lake, we spotted a lone coyote pouncing for mice. After descending over grassy knolls like pastel pincushions covered with lilliputian flowers, Rich fly-fished, and caught 10-inch rainbow trout on almost every cast. Will napped in the shade of dwarf junipers. I eyed the peaks.

The next day I got my chance. Rich took Will rock-hopping and fish-scouting around Twin Crater Lakes. I went peak-bagging. After a steep ascent over scree-strewn talus I reached the top of South Rawah Peak, to a rewarding 360° 100-mile view in all directions. Most dramatic was the view west, to the Continental Divide a mountain range away, and south, to the jagged 14,000-foot summits in Rocky Mountain National Park and the Indian Peaks. A Chilean alpinist joined me for the final ascent and kindly lent me his ice ax to use as a glissading aid. I arrived back in camp after some hair-raising schusses down steep but soft snow.

On the way to another trout-filled lake the third day, we picnicked in the shade of a huge granite boulder near yet another patch of snow. Rich taught Will how to throw snowballs. Skinny-dipping was on the agenda, but the water, though inviting to look at, almost knocked us out, so Rich and I each dunked for mere seconds, shouting with the shock of dipping into fresh snowmelt. Will refused to dunk himself, preferring to laugh at us from the grassy, columbine-strewn edge.

Will's Opa, my father, a 68-year old veteran backpacker from whom I got the hiking bug, joined us for our final night. Late in the afternoon, we spotted him slowly picking his way through the mud and snow over the last rise (he had called Stan to find out exactly where we were camped). Though ebullient to have found us, Opa was eager to chuck his daypack and rest after the seven-mile uphill climb. Three days prior, the llamas had brought the bulk of the gear he needed for the night.

The next morning, Will and Opa enjoyed some time together in the early fresh air. Strolling around the lake, they were accompanied at close range by bighorn sheep mothers and babies looking for new grass peeping out from the receding snowline. Meanwhile Rich and I packed the gear into the saddle bags. The llamas and Stan arrived promptly at 10:30 and after a little kushing time for the llamas, all three generations of hikers headed back down to civilization.

Back to the Wilderness

Hooked, we returned to the western wilderness only seven months later. The high Rockies had been a hydric experience, with plentiful water and wildlife, to which we had to climb up thousands of feet. This time we hiked flat, arid canyon country where, instead of wildlife, we would seek traces of the Anasazi that had flourished a thousand years before.

Buckhorn again provided us with llamas, from their base in Bluff, Utah at the western edge of the Colorado Plateau. Mid-March is the cusp of the Spring hiking season and weather is risky. The llamas gave us the margin we needed to bring gear enough to prepare for 80°F days, freezing nights and the possibility of snow or torrential rain, in addition to blasting hot sun.

The Fish and Owl Creek Loop at the southeastern corner of Cedar Mesa is well-known among backpackers seeking to avoid the crowds that descend upon Grand Gulch, the National Monument just to the west that is famous for the density of Anasazi Ruins lining its canyon walls. Like Grand Gulch, Fish and Owl is managed by the Bureau of Land Management but is under significantly less regulatory pressure. While we still needed a stock permit, our dog was not required to be leashed (editors note: this regulation has since changed: dogs are still allowed, but must be leashed), and cattle still graze at the mouth of the lower canyons.

Our Utah Canyon Campsite

Compared to the Rawah, the hike in was a stroll. The trail began at a rift west of Comb Ridge. This 600-foot high umber and sienna sandstone monocline was a lively crossroads for pre-historic pueblo groups. Later, the Mormons travelled along its flank–the ruts from their wagons are still visible. The spot where the wrangler Larry Sanford loaded our llamas is marked by a massive slab of slickrock covered with rock art that serves as a tantalizing introduction to the rich offerings we would behold deeper in the canyons. This time, Will was prepared in advance for the drama of the llamas. Now two and a half, he quickly learned the llamas' names and fed them treats out of his hand.

We followed Lower Fish Creek upstream as it meandered through the canyon at a shallow, barely noticeable grade. The stream grew thinner, then became intermittent. The area had been plagued by mild drought for three seasons running. Five hours and six miles later, we were parched. Larry and Rich relieved the llamas of their load. We set up camp on a sandy bench overlooking the only water hole we'd seen in miles.

Ruins, Arches & Hoodoos

The following morning, mere feet from our tent, we found well-worn backpackers' trails to cliff dwellings. Little pits in the dirt held fragile, weather-worn treasures of worked bone, tiny ceramic beads and painted pottery remnants. We fingered the collection and supervised Will's exploration of the intact former granary, including the pitch black, cool interior. The mud brick shaped by human hands long ago looked as if it could have been set yesterday. Touching this handiwork, we felt connected to a long stream of humanity and a uniquely American legacy of civilization.

What is a trip to Utah without arches? On each of our two full days in the backcountry, we made an arch our destination, keeping our eyes peeled for ruins along the way. The sun beat down on us like lead. Shade was scarce along the way to Neville's Arch, a jagged span deep up Owl Creek Canyon. Almost 500 feet beneath its upside-down smile, we cavorted in the first water we found, four miles from camp. The water felt soapy, its alkalinity derived from the limestone layers laid down when the area was a sea.

Along Upper Fish Creek Canyon the following day, the arch we sought eluded us. Instead, we amused ourselves anthropomorphising the many "hoodoos," the strange, bulbous spires formed by erosion on top of the sandstone cliffs. Multiple-trunked cottonwoods, like huge octopuses, shaded Will while he napped.

Later he insisted on taking the lead along the flat, sandy trail, periodically yelling, "Come ON, guys," or "Cactus alert!" On the way out the next day, Will chanted the llamas' names like a mantra and even stroked the friendliest one. The beasts waited patiently while we stopped to rest at numerous cliff-dwellings. Will reveled in the ruins, which seem naturally scaled to toddlers.

Back home in Connecticut, Will recently first experienced overnight camping without his wooly Andean pals. When he saw Daddy hoist a large pack, he asked, "Where are the llamas?"

Rich and I could only laugh, but we missed them, too. While we hiked along, if we weren't too out of breath, we tried to hum like llamas do when they're happy.

Where to Find Pack Llamas

Buckhorn Llama Company (970/667-7411) located at 7220 North County Rd 27, Loveland, serves Colorado and Southeastern Utah. Owners Stan and Dianne Ebel were pioneers in bringing llamas to a broader audience in North America starting in the late 1970. The main ranch, including the breeding herd, educational exhibits and a store well-stocked with llama paraphernalia, is in the foothills of the Front Range of the northern Colorado Rockies.

Lander Llama Company (307/332-5624), located at 2024 Mortimore Lane, Lander WY 82520, has run llama trips since 1985. Founded and run by Scott and Therese Woodruff, it serves the Wind River Range and other areas of western Wyoming. The website includes a fun newsletter, "Llameros."

Information about other outfitters, ranches and llama miscellanea can be found by browsing the Internet and visiting such sites as www.llamaweb.com.

Recommended Reading for Kids about Llamas & Hiking

On Llamas:

If I Was a Llama, by Ann Marsh Madison (Illustrator). LRL Ventures, Cisco, Texas (self published)

Llamas (A True Book), by Emilie U. Lepthien (includes photos). Children's Press, a division Scholastic Library Publishing, 1996.

Stop Spitting at Your Brother, Life Lessons of a Rocky Mountain Llama, by Diane White-Crane (Illustrator). Aspentree Press, 1996.

On Hiking:

Desert Trip, by Barbara Steiner and Ronald Himler (Illustrator). Sierra Club Books for Children. 1996.

Tracks, Scats and Signs, by Leslie Dendy and Linda Garrow (Illustrator). NorthWord Press, Minnesota. 1998.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.

I would spray Rataway fragrance from Rataway.com . Rataway Fragrance is non-poisonous and non-toxic.

To protect food place food in a plastic bag or box and spray bag with Rataway Fragrance. Also use Rataway fragrance to protect car engines, computer cables, wiring, air conditioning equipment,camping supplies, etc…. Stops rats, mice, rodents, monkeys, etc from nesting & chewing.