All my worries seemed so far away. I was walking with Bernadette while holding her hand on Boracay Beach as if nothing could separate us. Just the cool breeze and the graceful tides touched us. She stumbled purposefully, pulling me down to the sands with her. We were staring at each other silently before the sun set. Her lips were like a magnet pulling mine. Five more inches before our lips were locked . . . . Four more . . . . Two more . . . . One more . . . BEEP BEEP . . . BEEP BEEP . . . BEEP BEEP. Smack! I glared at the alarm clock, but all he could do was taunt me with his four o’clock smile.

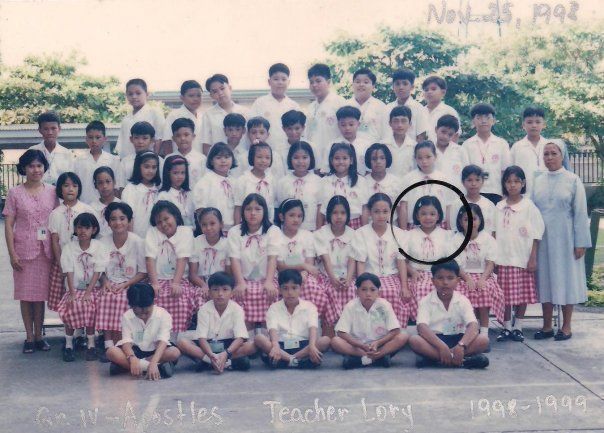

I knew I had to wake up early for my flight to North Carolina, but I would’ve rather missed the plane than miss my paradisiacal dream. The fact that I would not be able to see Bernadette after leaving the Philippines paralyzed me in my bed; I could have cared less about my unpacked baggage. Bernadette was my girlfriend in our sixth-grade class at Don Carlo Cavina School. She interacted with grace with our schoolmates. Her sweet smile, her lilting voice—as if her larynx was made of harp strings, and her mellow personality endeared her to all. Though I had not been raised Catholic, Bernadette’s otherworldly beauty made me think of the Virgin Mary, whose serene visage appeared in framed paintings throughout the school.

I was raised here, in my grandma’s house where the whole family used to live. My mother moved to North Carolina when I was eight years old to marry my current stepfather and to work there as a nurse at UNC. A thirty-minute drive from my grandma’s house to a townhouse in Cavite was the price of having a thirty-minute stay with my biological father, his wife, and my five-year-old stepbrother. It was funny how both of my parents’ weddings were held when I was nine years old, and I was absent from both. I thought that I was lucky to have two families, but soon realized that I was not; I never felt a sense of belonging in either family. Instead, I spent my childhood and preteen years with three people: my grandma, our maid Luz and Auntie Janice.

*****

Luz, our maid, was forty years old and had been with our family before my mom was even born. I considered her like my second mother because she had taken care of me since I was a child. She scolded at me in Tagalog, “GET UP! GET UP! You need to be in the airport by six a.m., you know?”

“Ah; but it’s just four.” I turned away from her and sank my face into the pillow

“Look at your bag! It’s empty. Do you know how much things you need to bring to America? C’mon Jake, get up. We don’t have enough time.”

“Hbt mmmmpk mppphhh now?”

“What?”

I lifted my face away from the pillow so she could hear me clearly, and said once more, “How bout you back my bag?!”

“Jake, I already did that last night, but you emptied it out again cuz you didn’t like the way I organized it. I don’t know what else you want to bring.”

“Okay! Okay!” I rushed to the bathroom to shower. In fact, the smell of tocino made my stomach grumble, and made me want to escape my meditation in the bathroom. I rushed to the wooden dining table, grabbed a cup of coffee, and filled my plate with tocinos, sunny-side-up eggs, and rice. I pushed big spoonfuls of all three into my mouth. If a spectator were to view my breakfast in slow motion—if we could stop the hourglass’s sands from spilling—he would see me dribbling two-fifths of the cup of creamed Nescafé on my sweater, scattering rice as the spoon clinked against my braces, strewing eggshells like sediment on the floor tiles, rustling sauced napkins about like the crackling leaves of fall, all accompanied by the constant cries of grandma. She was screaming, “Ucha ucha ucha ucha,” which means “HURRY UP!”

It was five o’clock and the kitchen window was a blur, showing the quiescent dusk’s pale blue stratosphere where a couple of love birds were chasing each other. I imagined myself as one of them but in a newspaper’s scenario, as if a tsunami or hurricane had carried me far from the ones I loved. I felt a tearless cry rise in me. There was nobody to blame. It was as though moving away was a part of nature’s cycle, whirling loop-de-loop around the eye of the hurricane. We were ready to leave. The luggage was full with things that broke the zippers. The Toyota Tamaraw’s motor was chugchugchugchugchugchuging, ready-to-roll to the airport, and Raymond was inside, looking as if he had sore eyes. Everybody knew he was holding back his tears. The gates were open. Good-byes were just made up of numb pauses. It felt so awkward going through our fast-forward preparations and suddenly, when we were finally ready to go and time was kissing our departure, everything just stopped as if we feared to stand up from the dining chairs. We feared moving to the future and feared to embrace the past. We believed that America would offer more opportunities for us than the Philippines, yet this was where we were born, where we grew up, and where we made friends whom we did not want to let go. I wanted to escape the political corruption that had created such misery in my native land, but a part of me was wiping my feet on the front door’s welcome mat, preparing to enter and never leave grandma’s house.

I walked out of the home where I had lived for twelve years, looking at its red roofs; the cement driveway where I accidentally scratched a visitor’s car while riding a bike; the basketball hoop that grandma had bought me and had installed that drew scores of friends for pickup games; and the stone hedge under the tree where friends and family lingered to feel the fresh winds that come and go.

Everything outside and inside the house gave me flashbacks of my childhood. Although the house itself was the melody of our farewell song, the crescendos came from those who were inside the house: Grandma and Luz. They were standing in front of the gate as we loaded our bags into the Toyota. Before we swooshed through the roads filled with traffic, I saw Luz smiling, happy for us yet with tears around her eyes. I felt bad seeing her sadness. It made me feel lonelier. She was always there for me when my mother was in America. I felt I owed her my life. She was my angel of unconditional love.

She said weakly, “Bye, Jake.”

I just shrugged and “Bye,” as if I did not care. I’ve regretted it since. Luz was left behind to supervise the house while Grandma and Raymond drove us to the airport.

The sun was awake, gleaming across the Toyota’s windshield and side mirrors as Auntie Janice watched her tears mix with her makeup. This was the only time of day when the highways were not crowded with bumper-to-bumper traffic. The roads were narrow, polluted, and traffic lights were as rare as autographed jerseys.

We passed through the littered markets where vendors were selling their goods. The smell of fish and char-grilled burgers swept our double-faced selves .The honking of jeeps and other vehicles was as loud as roosters cuckooing in our ears. We arrived at the international airport, facing a fork that divided “ARRIVAL” and “DEPARTURE” areas. Airports are like no other places. They make you cry and smile at the same time. We were dropped in front of the Northwest Airlines spot in the departure lane, and entered the tinted doors where a couple of security guards checked our tickets. At this point, Raymond and Grandma were not allowed to enter. I said “Good-bye” to both of them as if I was just about to skate to America and come back home twenty minutes later to see them again, but this was it. Raymond kissed Auntie Janice and hugged her tightly. They waved farewell to us.

Liters of tears later, we were in front of the desk to check our baggage and have our passports and plane tickets verified by a woman who had her eyes locked on a computer monitor. She was typing rapidly, as if letting go of the keyboard would detonate a bomb. After a lengthy examination of our documents, while my aunt’s “hoohoohoos”resonated in the background, she said, “I’m sorry, but your passports are expired. You can’t board the plane.” With our emotions turned upside down, Auntie Janice and I looked at each other’s faces, but they looked the same as always: tearful and joyful.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.