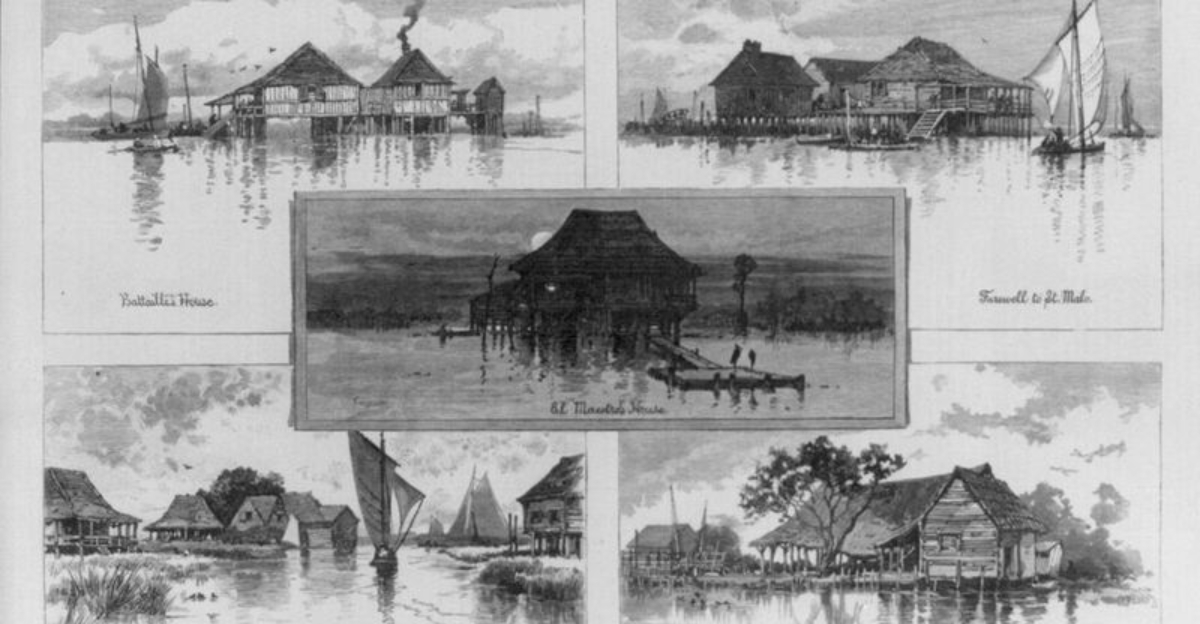

Hidden deep in the Louisiana marshes once stood a village that changed American history forever.

St. Malo was home to brave Filipino sailors who built their lives far from home, creating the first Asian settlement in North America.

Their incredible story of courage, survival, and community remains mysteriously absent from most history books, even though it happened centuries before the gold rush or railroad workers arrived out West.

1. America’s First Asian Settlement Started in 1763

St. Malo became home to Filipino sailors nearly a hundred years before other famous Asian communities appeared in America.

While history classes talk about California’s Chinatowns from the 1850s, this Louisiana village was already thriving during George Washington’s childhood. The Manilamen who founded it escaped Spanish ships and chose the wild marshes as their new homeland.

Most textbooks skip right over this amazing fact because it doesn’t fit the typical immigration timeline teachers follow. Colonial-era Asian settlements weren’t supposed to exist according to standard history lessons. Yet St. Malo proves that America’s multicultural story started way earlier than anyone realizes, right there in the swampy Louisiana territory.

2. Government Records Barely Mention This Hidden Community

The sailors who built St. Malo weren’t interested in filling out paperwork or paying taxes to Spain. They had jumped ship to escape their old lives, so staying off official records kept them safe and free. Without census data or legal documents, historians found almost nothing to study for centuries afterward.

This invisibility in government files made it super easy for textbook writers to ignore the settlement completely.

Schools teach what’s written down in official sources, and St. Malo left barely a trace. The community thrived in secrecy, which protected them then but erased them from history lessons now, creating a frustrating gap in what students learn about early America.

3. Spanish Louisiana Gets Ignored in American History Classes

When St. Malo was founded, Louisiana belonged to Spain, not Britain or France or the United States. Most history textbooks zoom in on the Thirteen Colonies along the Atlantic coast and barely glance at what Spain controlled.

The Gulf South’s colonial story gets squeezed out to make room for Boston Tea Parties and Valley Forge winters. Spanish territories like Louisiana had their own fascinating histories with different cultures mixing together.

Teachers rarely have time to cover these areas because standardized tests focus on the Revolutionary War and westward expansion. St. Malo’s story falls into this blind spot, a victim of curriculum choices that prioritize certain regions while leaving others in the shadows of forgotten history.

4. The Manilamen’s Journey Doesn’t Fit Standard Immigration Stories

Immigration lessons usually follow a familiar pattern: Europeans arriving at Ellis Island or Chinese workers building railroads. The Manilamen’s path to America was totally different and way more complicated. They sailed the Manila Galleon Trade route across the entire Pacific Ocean, working for Spain before escaping in Louisiana’s waters.

Their unique journey confuses the neat categories textbooks like to use when explaining who came to America and why. Teachers prefer straightforward narratives that students can easily remember for tests.

The trans-Pacific connection between the Philippines and Louisiana involves Spanish colonial economics, which adds layers of complexity that curriculum planners often avoid, leaving this remarkable migration tale untold in classrooms nationwide.

5. A Devastating Hurricane Erased St. Malo from the Map

In 1915, a massive hurricane slammed into the Louisiana coast and completely destroyed St. Malo. The storm’s fury left nothing standing; no buildings, no docks, no evidence that anyone had ever lived there. The remote marshes swallowed up what little remained, and the physical village simply vanished from existence.

Without ruins or landmarks to visit, tourists never flock to the area asking questions about its past. Historic sites usually survive because buildings remain standing for generations, sparking curiosity and preservation efforts.

St. Malo had no such luck, disappearing so thoroughly that even local residents forgot the exact location over time, making it nearly impossible for historians to study or for textbooks to feature prominently.

6. Connections to Pirates Made This Story Less Textbook-Friendly

The Manilamen weren’t just peaceful fishermen minding their own business. They fought side-by-side with Jean Lafitte’s notorious pirate crew, who controlled smuggling operations throughout the Gulf Coast.

Some St. Malo residents also helped escaped slaves hide in the marshes, creating communities that colonial authorities considered dangerous and illegal. Textbook publishers prefer stories about respectable immigrants who followed the rules and contributed to society in obvious ways.

Piracy and harboring runaways don’t fit that wholesome narrative teachers want for middle school students. The messy, rebellious reality of St. Malo’s history makes curriculum committees uncomfortable, so they skip it entirely rather than explain the complicated moral landscape of colonial Louisiana to young learners.

7. Their Heroic Role in the Battle of New Orleans Gets Overlooked

When British forces attacked New Orleans in 1815, the Manilamen joined Andrew Jackson’s desperate defense. Their incredible shooting skills and knowledge of the swampy terrain proved crucial to America’s surprising victory.

These Filipino fighters knew every inch of the marshes and could navigate conditions that confused British soldiers completely. History books love talking about General Jackson’s brilliant strategy but rarely mention who actually did the fighting.

The diverse coalition that saved New Orleans included people from many backgrounds, yet textbooks simplify it to focus on famous white generals. The Manilamen’s bravery gets lost in this oversimplification, leaving students with an incomplete picture of who really won one of America’s most celebrated military victories.

8. Intermarriage Created Confusing Racial Categories for Record-Keepers

St. Malo’s residents married people from surrounding communities; Creole women, Spanish settlers, Native Americans, and others. Their children and grandchildren represented beautiful blends of cultures that didn’t fit into the rigid racial boxes that government clerks used. Later historians struggled to classify these families when writing about Louisiana’s population.

Textbooks prefer clear categories that students can memorize easily: European, African, Asian, Native American. Real life is messier than that, especially in colonial Louisiana where cultures mixed freely.

The Manilamen’s descendants became part of the region’s complex Creole identity, which confuses simple narratives about immigration and ethnicity that standardized curriculums require, resulting in their omission from mainstream historical accounts taught in schools.

9. Textbooks Focus Almost Exclusively on West Coast Asian History

When teachers cover Asian-American history, they almost always start with Chinese immigrants during the California Gold Rush and railroad construction.

These mid-1800s events happened on the West Coast, thousands of miles from Louisiana. The curriculum jumps straight to Angel Island and discrimination laws without ever mentioning the Gulf South. This geographical bias means students learn that Asian-American history began in California and stayed there for generations.

St. Malo’s story happened a century earlier on the opposite side of the continent, but it gets ignored because it doesn’t fit the established narrative structure. East Coast and Gulf Coast Asian communities remain invisible in most classrooms, creating a seriously incomplete understanding of how diverse America actually was from its earliest days.

10. The Tragic Tale of Juan San Maló Remains Unknown

The village’s name connects to Juan San Maló, a brave leader of escaped slaves who built a free community in the same Louisiana marshes. Spanish authorities hunted him down in 1784 and publicly executed him in New Orleans as a warning to other runaways.

His story is both inspiring and heartbreaking, showing the desperate fight for freedom in colonial America. Textbooks rarely discuss Maroon communities; groups of escaped slaves who formed their own settlements in remote areas.

Juan San Maló’s execution and his connection to the Filipino fishing village add complicated layers to Louisiana’s slavery history. Teachers already struggle to cover slavery adequately in limited class time, so these regional details get cut despite their dramatic human interest and historical significance.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.