Standing at the edge of Cornucopia, I felt something shift in the air around me. Maybe it was the wind whispering through the skeletal remains of century-old buildings, or perhaps the weight of all those forgotten dreams still lingering in the mountain shadows.

This abandoned mining settlement in the Wallowa Mountains of eastern Oregon carries stories that refuse to stay buried.

Gold brought thousands of hopeful prospectors here in the 1880s, but when the federal government shut down non-essential mining operations in 1942, Cornucopia became frozen in time.

Walking these overgrown streets today, you’ll find tilting structures, rusted equipment, and an eerie quiet that makes your skin prickle. The isolation is profound, the forest dense and watchful.

Even under bright sunshine, there’s an unmistakable chill that settles into your bones and makes you wonder who might still be watching from those empty window frames.

Gold Rush Origins and the Town’s Explosive Birth

Back in 1884, prospectors struck gold in these rugged mountains, and suddenly everyone wanted a piece of the action.

Within months, a tent city sprouted like wildflowers after rain, filled with miners, merchants, and dreamers who believed fortune was just one pickaxe swing away.

The town was officially platted in 1886, and by then, Cornucopia had transformed from a rough camp into a legitimate settlement complete with hotels, saloons, and even a newspaper. The name itself came from the mythological horn of plenty, reflecting the optimism that gold would flow endlessly from these hills.

During its peak years, the population swelled to over 700 residents, all crammed into this remote valley accessible only by treacherous mountain roads.

Mining companies dug deeper, extracting millions of dollars worth of gold and silver from the surrounding rock.

I walked the same paths those early miners once traveled, imagining their excitement mixed with desperation. The bones of their ambition still lie scattered across the landscape, a testament to both human determination and the harsh reality that not all dreams pan out the way we hope.

The Crumbling Hotel That Still Stands Watch

Among all the structures still defying gravity in Cornucopia, the old hotel commands the most attention.

Its wooden frame leans at an angle that seems to challenge physics, as if it’s perpetually deciding whether to collapse or hold on for one more season.

When I approached this building, I noticed how the windows gaped like hollow eyes, their glass long since shattered or stolen. The porch sagged dangerously, groaning under its own weight, and I didn’t dare test whether it could support mine.

This hotel once hosted weary miners after long shifts underground, offering them warm meals and soft beds, luxuries that felt like heaven after days of backbreaking labor. Now it hosts only shadows and the occasional curious visitor brave enough to peer inside.

The interior reveals peeling wallpaper, collapsed ceilings, and doorways leading to rooms where countless stories unfolded.

Standing there in broad daylight, I felt an inexplicable chill, as though the building itself remembered all the laughter, arguments, and exhaustion that once filled its halls and wasn’t quite ready to let those memories fade into silence.

The 1889 Jailhouse and Its Dark Reputation

Few buildings carry as much unsettling energy as the jailhouse constructed in 1889.

This small structure served as the town’s only means of dealing with troublemakers, claim jumpers, and the occasional miner who’d had too much fun on payday.

The jail’s thick log walls and tiny barred windows speak to the rough justice that prevailed in these mountains. When I peered through those bars, I could almost hear echoes of angry voices and desperate pleas bouncing off the cramped interior.

Mining towns attracted all types, and not everyone came to Cornucopia with honest intentions.

Disputes over claims sometimes turned violent, and this little building became the temporary home for men whose tempers or greed got the better of them.

What strikes me most is how isolated prisoners must have felt, locked in this tiny cell with nothing but mountain wilderness stretching for miles in every direction. There was no easy escape, no quick trial, just waiting in the cold darkness while the town decided your fate.

Even now, standing outside in brilliant sunshine, the jailhouse radiates a heaviness that makes you want to step back and catch your breath.

The 1942 Closure That Sealed Cornucopia’s Fate

World War II changed everything for Cornucopia, though no bombs ever fell on these remote Oregon mountains.

In 1942, the federal government issued Order L-208, closing all non-essential gold mining operations to redirect resources and labor toward the war effort.

For a town whose entire existence revolved around extracting precious metals from the earth, this order was a sentence without appeal. Miners packed their belongings, families boarded up their homes, and within months, the bustling community had emptied out like water from a broken bucket.

Some residents believed they’d return once the war ended, but most never came back. The mines stayed closed, the equipment rusted in place, and Cornucopia slipped into a sleep from which it would never wake.

Walking through the town today, I tried to imagine that final exodus, families taking one last look at the place they’d called home before heading down the mountain road.

The suddenness of the abandonment explains why so much was left behind, as if everyone expected to return next week.

That frozen-in-time quality adds to the eerie atmosphere that makes your spine tingle even when the sun is high overhead.

Dense Forest Surroundings That Amplify Isolation

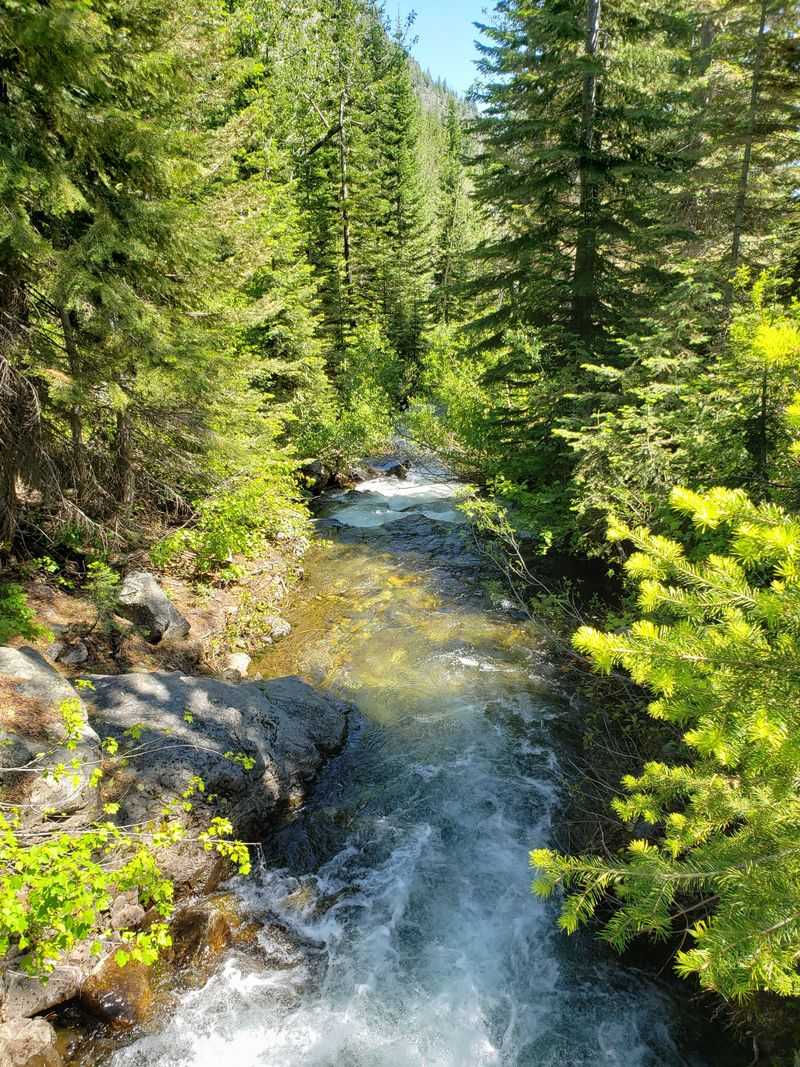

Cornucopia sits cradled in a narrow valley, hemmed in by steep mountainsides covered in dense evergreen forest. The trees press close to the remaining buildings, as if nature is slowly reclaiming what humans briefly borrowed.

This isolation is profound and palpable. Modern Cornucopia lies at the end of a rough dirt road that winds through miles of wilderness, far from any highway or populated area.

Cell service is nonexistent, and the nearest town with actual residents is a long drive away.

The forest creates an acoustic effect that makes every sound feel both amplified and muffled at the same time. Birds call from the canopy, branches crack underfoot, and occasionally you’ll hear something moving through the underbrush that you can’t quite identify.

When I visited, the trees created pockets of deep shadow even at midday, and stepping from sunlight into those shaded areas felt like crossing an invisible threshold. The woods seem to watch, patient and ancient, knowing they’ll eventually swallow every last trace of human ambition.

That certainty, combined with the remoteness, creates an atmosphere that would unsettle even the most rational visitor.

Rusted Mining Equipment Scattered Like Monuments

Everywhere you look in Cornucopia, you’ll find remnants of the mining operation that once drove this town’s heartbeat. Rusted ore carts sit frozen on deteriorating tracks, their wheels seized decades ago.

Cables dangle from old pulley systems, and mysterious pieces of machinery slowly dissolve into the soil.

These artifacts tell stories more eloquently than any history book. Each piece of equipment represents investment, hope, and countless hours of brutal labor extracting gold from stubborn rock.

I spent time examining a massive piece of machinery near one of the mine entrances, trying to puzzle out its original function. The metal had oxidized into beautiful patterns of orange and brown, nature’s artwork painted over human engineering.

What strikes me most is how quickly the forest has begun to integrate these objects into the landscape. Moss grows on gears, saplings push through broken frames, and what once represented cutting-edge technology now serves as habitat for insects and small animals.

The equipment stands as monuments to ambition and eventual futility, reminders that all our grand projects eventually return to dust and rust beneath Oregon’s persistent rain and snow.

Visiting Conditions and Access Challenges

Getting to Cornucopia requires commitment and a vehicle capable of handling rough conditions.

The final stretch involves navigating a dirt road that can become impassable during wet weather or winter months, when snow blocks the high mountain passes.

Most visitors arrive during summer and early fall, when the road is most reliably accessible. Even then, you’ll want high clearance and preferably four-wheel drive, as the route includes steep grades, loose rocks, and sections that test your vehicle’s suspension.

There are no facilities at Cornucopia, no restrooms, no water sources, and definitely no cell phone coverage. You’re truly on your own once you arrive, which adds to both the adventure and the slightly anxious feeling that accompanies exploring such an isolated location.

I recommend bringing plenty of water, snacks, a full tank of gas, and letting someone know your plans before heading up.

The remoteness that makes Cornucopia so atmospheric also means help is very far away if something goes wrong.

That combination of beautiful scenery and genuine isolation creates an experience that feels both thrilling and slightly dangerous, keeping your senses alert throughout the visit.

The Eerie Quiet That Settles Over Everything

One of the most unsettling aspects of Cornucopia is the profound quiet that blankets the entire area. Without traffic, voices, or the hum of modern civilization, the silence feels almost physical, pressing against your eardrums.

This isn’t the peaceful quiet of a serene meadow or gentle forest. Instead, it’s a loaded silence, heavy with absence, as if the town is holding its breath and waiting for something to happen.

When wind moves through the buildings, it creates sounds that your brain struggles to categorize. Is that a door creaking open, or just wood expanding in the heat?

Did something move inside that window, or was it just a shadow shifting?

I found myself speaking in whispers without quite knowing why, as though raising my voice would be disrespectful or dangerous. Every footstep on the old wooden sidewalks echoed louder than seemed natural, announcing my presence to whatever might be listening.

The quiet amplifies your awareness of every small sound, turning ordinary forest noises into potential threats or mysteries. It’s the kind of silence that makes you understand why people report feeling watched, even when there’s clearly no one else around for miles.

Dear Reader: This page may contain affiliate links which may earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Our independent journalism is not influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative unless it is clearly marked as sponsored content. As travel products change, please be sure to reconfirm all details and stay up to date with current events to ensure a safe and successful trip.